Writers often draw upon history, be it for inspiration, for setting, for character, for plot ideas, or for some combination of these. Recently, I have embarked on a new phase in my career, turning from epic fantasy to what I call historical urban fantasy. And even as I borrow so many of my ideas from the past, I find myself wondering what I owe history in return.

Writers often draw upon history, be it for inspiration, for setting, for character, for plot ideas, or for some combination of these. Recently, I have embarked on a new phase in my career, turning from epic fantasy to what I call historical urban fantasy. And even as I borrow so many of my ideas from the past, I find myself wondering what I owe history in return.

I have a Ph.D. in U.S. history, and though I have been a refugee from academia for far longer than I was actually a part of it, I still harbor a certain reverence for the study of our past, and a near-obsessive concern for historical accuracy. I also understand that “accuracy” is a term that is both freighted with unintended meanings and nearly impossible to define for more than one person at any given moment. Still, to the extent possible, I want to get the easily-verified stuff right. I want to put the correct people in the correct place at the correct time.

The first thing I owe to history: attention to detail. This is not to say that I can’t bend some “facts” to my own purposes.

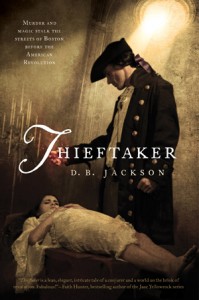

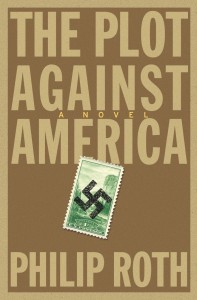

That I believe, is the first thing I owe to history: attention to detail. This is not to say that I can’t bend some “facts” to my own purposes. Authors do that all the time. Indeed, often that is the point of our work, whether it’s giving the Confederacy superior weaponry — as Harry Turtledove famously did in The Guns of the South — or having Charles Lindbergh, an anti-Semite and white supremacist, defeat Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 Presidential election — as Philip Roth did in The Plot Against America. In my new book, Thieftaker, I portray Boston in 1765 as accurately as possible, with two notable exceptions: First, in my book the city’s population includes some people who are conjurers, and second, the city has at least two thieftakers working within its boundaries. I’ll leave a discussion of magic and conjuring for another day, but I will readily admit that thieftakers did not actually appear in any North American city until the early 19th century and then only for a very brief period.

Boston, c. 1768

So, one may ask, if we can add thieftakers and conjurers to a city population, or give modern machine guns to the army of the Confederacy, or change the outcome of a Presidential election that occurred over seventy years ago, all in the interests of satisfying our narrative needs, how could it possibly matter what color Samuel Adams’ house was painted? And while I know it’s not a satisfactory answer to the question, I will start by saying “Because it just does.”

At this point it might be helpful to distinguish between “history” and historical details. Details are those things writers use to bring to life our settings, our characters, our narratives. Samuel Adams, who plays a substantial role in the Thieftaker books, was born in 1722. He had blue eyes. For nearly all of his adult life, he suffered from a mild palsy that made his hands and head shake. These are details, demonstrably true and helpful in giving my readers of sense of the man as he appears to my characters.

Adams was also a radical Whig who led the movement toward separation from the British Empire. This is “history,” and so somewhat debatable. Most books about Adams portray him this way, but some view him as less radical than his friend James Otis, and others see him not so much shaping events as responding to them opportunistically. History, to my mind, is more slippery than detail. It is, ultimately, subjective, even though it is often assumed to be “true.”

Adams was also a radical Whig who led the movement toward separation from the British Empire. This is “history,” and so somewhat debatable. Most books about Adams portray him this way, but some view him as less radical than his friend James Otis, and others see him not so much shaping events as responding to them opportunistically. History, to my mind, is more slippery than detail. It is, ultimately, subjective, even though it is often assumed to be “true.”

Recently Daniel Abraham and Kate Elliott posted wonderful essays here at A Dribble of Ink touching on the dangers of accepting social, cultural, and historical generalities as “truth.” For the author of historical fiction, the point of research should not be to confirm well-established, and often false, assumptions, but rather to discover those details that best supplement our prose and to get a sense of the historical narrative into which we are inserting our characters and storylines. And to build on Daniel and Kate’s points, I discovered in Boston a fluid social structure in which women, particularly widows, enjoyed greater financial and social independence than one might expect, and in which free persons of color could also find economic opportunity. The Boston I have created for the Thieftaker books reflects these historical realities.

As I apply magic and counterfactual plot points to events and people, I feel a certain obligation to tread gently on the existing terrain.

But I believe that there is a larger point to their posts, and to this one as well. As I delve into history for fictional purposes, and particularly as I apply magic and counterfactual plot points to events and people, I feel a certain obligation to tread gently on the existing terrain. History belongs to all of us, and I want to respect that communal ownership by not playing too fast and loose with historical figures and landmark moments that hold a special place in our cultural psyche. This, I believe, is the second thing I owe to history.

Let’s return for a moment to Philip Roth’s book. Yes, he turned history on its head, but notice what he did now do. He did not transform Franklin Roosevelt’s Administration into a vehicle for anti-Semitism or racial bias. He did not ascribe religious and racial intolerance to some other Republican contender for the 1940 nomination. Lindbergh was actually on record as having said some pretty disturbing things about Jews and African-Americans, and so Roth put him in a fictional White House and then carried that notion to its logical conclusion. Just as he should have.

In the same way, I will borrow from history; I will bend certain elements of history to the needs of my story. But I will also respect history. I am acutely aware of the fact that when I use Samuel Adams or James Otis or Thomas Hutchinson in my books I am borrowing them from America’s collective historical consciousness. They don’t belong to me. I don’t believe that I can do with them whatever I wish. I can portray Samuel Adams as prickly, even arrogant at times — because he was seen that way by a good number of his contemporaries. But I would never make him a villain, a traitor to his cause. In short, I would not feel comfortable challenging at a fundamental level his status as a respected historical figure.

These are my own rules and I apply them only to my own fiction. Other writers might not feel the same obligation to history that I do. That’s fine. But as I delve deeper into the Thieftaker universe, as I write about other historical events that have become touchstones of American identity, I find I need a set of guidelines that together form a coherent ethic. Thus, I will use history for my stories and books. I may bend the facts a bit to make my readers believe that a conjurer and thieftaker could interact with officials of the Crown and leaders of Boston’s burgeoning Revolutionary movement. But I will also treat that history the way I would a family heirloom. Because in a sense, that’s exactly what it is.

Great piece. I would think that part of the FUN of being an author who works in established history would be the need and subsequent attempts to match up the invented narrative with actual events. Like a jigsaw puzzle. It actually makes me have significant respect for Historical Fiction authors (like yourself, or Cornwell or Young, or Whyte)….things like Jack Whyte being able to retell the Arthur mythos and line up his narrative with the actual pulling of the sword from the stone was…impressive to say the least. I think I’m going to put Thieftaker on my list sir! Thanks!

Many thanks for the comment, Scott, and for your interest in THIEFTAKER. Your analogy of the jigsaw puzzle is spot on. Piecing together the events surrounding the Stamp Act riots with my own narrative for the novel took time and effort, but the more pieces I had in place, the easier it became to find the right spot for the next one. It’s enormous fun, actually — the second Thieftaker book was every bit as challenging and rewarding to write as the first.

[…] is called “What do Authors of Historical Fiction Owe to History?” and it can be found here. Come on over to Aidan’s site and join the conversation. I’ll be checking in […]

I’d probably never have picked up your book without reading something like this, but I thought you argued a point really well that I feel strongly about, and I’m interested to see how it bears out in your fiction. I recently read Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and while I respect Smith’s motivations, I just kept thinking to myself that the dude could really benefit from employing a thoughtful trained historian who could help him not just present surface-level wikipedia-level facts, but also complicate common perceptions and mis-perceptions about his subject matter.

You’ve expressed a great position that I may refer back to when I have discussions with others on the subject. Thanks!

Thank you, Neal. I have not read Grahame-Smith’s book, although I’m intrigued by the concept (and by the movie trailers). But I have to admit to also being leery of it for just the reasons you point out. Having just a little historical sensitivity is — in my opinion, with regard to my work — crucial. Being innovative, even daring, is cool. I’m fine with that, so long as it’s done with respect as well. I’m not saying Grahame-Smith hasn’t done this — as I say, I’ve not read the book. But as a reader coming to it, that would be my greatest concern. Thanks for a thought-provoking comment.

I also love the analogy of the jigsaw puzzle. I certainly appreciate when an author can get the historical facts correct, and then add in an entertaining story plot around the facts. This is something that I strongly felt Robert C. Yeager did in his latest historical novel, “The Romanov Stone.”

http://www.robertcyeager.com/

I tend not to read historical fiction for related reasons. It by definition does some violence to history, what with the whole fiction part. But with as much American history and fantasy as I read, I can’t really pass on a fantasy book set in late Colonial America, can I? I also don’t think the Enlightenment gets nearly enough attention from fantasy authors (although what I would REALLY like to see is it examined in a created-world).

Maybe the essential thing is to change as much as you need, but not an ounce more. That is, for example, make the necessary changes to incorporate magic (important to the story) but be accurate about clothing and building (unimportant to the story).