A young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

A minor noblewoman has a tragic love affair with an emperor. She dies, leaving behind her child — a young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

Welcome to the Tale of Genji, the Japanese story of romance, ghosts, poetry, and politics that has a good claim of being the world’s first novel. To clarify: Genji is a work of prose, not epic poetry, and written in the vernacular rather than the local courtly language (which, in early 11th century Heian Japan, would have been Chinese). It’s also, as far as we can tell, original, without folkloric or legendary precursor. The author, Lady Murusaki Shikibu, wove her hero and his, um, exploits out of whole cloth. And, while many other works deal with mythological high society—gods and demons and so forth—Murusaki seems to have cared a great deal about representing (idealistically but still) her social reality. Genji Monogatari is a work of beauty and passion and (to modern sensibilities) occasional utter weirdness, in which twenty chapters of plot turn on the accidental glimpse of one character by another through a paper screen, astrological prohibitions on travel are used to justify spending the night at a prospective lover’s house, titles take the place of names, violence is anathema, and a twenty-mile exile is worse than death.

Granted, Genji is less core epic fantasy than the tales on which my previous articles on this theme have focused: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, the Mahabharata, all these are expansive stories of magic, politics, and warfare that could put any doorstopper of your choice to shame. Genji, by contrast, is more contained and elegant. Yet the world it draws is so expansive, so similar to and different from our own at once, that the mind reels to conceive it, making it in a way more alien and fantastical and essential than the million-man wars of the other works.

By that I mean that in the fantasy genre we’re used to the stakes of battle—even those of us who aren’t soldiers have been told, often, that people die in war, it hurts, and ground is gained or lost with blood. This is easy to understand. (Or we so often assume it is, a point for a future essay.) More alien are the wages and risks and glories of love and friendship in different nations at different times. The sword elides cultural diversity; men and women are never more kin than when they face death at an enemy’s hand. It’s in comfort that difference emerges. And the Heian court is… different.

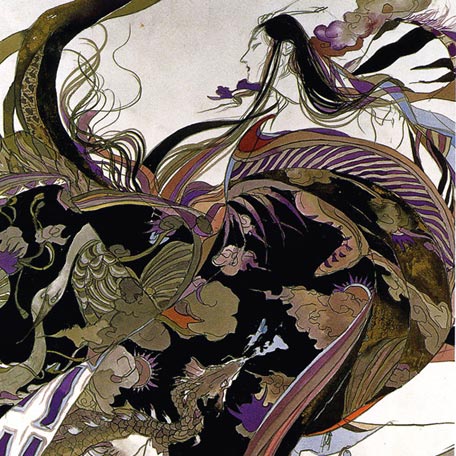

Art by Kekai Kotaki

When Genji Monogatari was written, Japan had been at peace for centuries. The Heian empire was, at this point, not militarized as we understand it, and as a result martial virtue does not seem to have been seen as a component of masculinity. Poets were lionized; swordsmen were regarded as dangerous deviants, and martial bearing and ability were signs of lower-class, if not criminal, status. The capital was a few miles across, but travel from one end to another could take hours due to the poor condition of the roads and the nobility’s reliance on heavy, ceremonially adorned ox-carts. There was an imperial examination system, copied (like much of Imperial tradition) from the Tang dynasty that ruled China a few centuries previously, but nobody seems to have paid it much attention. Corruption was rampant but not vicious. Noble residents of the capital derived their income from massive land holdings, but strived to avoid ever seeming to manage these holdings. The capital city was half-overgrown with vines and fallen into decay; at one point Genji has an assignation with a noblewoman who happens to live in an unfashionable district; she’s presented as if she lived in the most rube-ish of hinterlands, when in fact she’s maybe half a mile distant from his own house. We’re talking about an imperial capital that was once successfully invaded by a bunch of drunken monks from a neighboring mountain. With its lionization of perception, artistic accomplishment, romance, and ennui, the Heian court of Genji Monogatari seems at once alien and familiar—for all the costumes and the astrological prohibitions, the monastic retreats and the ghost possessions, Genji sometimes seems to be set in Hannah Horvath’s Brooklyn.

In form, Genji Monogatari is a chronicle of romance. After the book treats us to the story of the titular Hikaru Genji’s birth and childhood, we meet him as a young court nobleman obsessed with beauty and sadness. Chapter by chapter we receive the chronicle of his romantic adventures—sexy, hilarious, and painful by turns, replete with poetry and details of courtly life and behavior. But Genji’s exploits have consequences, both political (he’s punished with demotion and exile when his less honorable flings are revealed) and, in one of the book’s most haunting subplots, demonic.

You see, in Heian Japan people believed that jealousy and strong emotions could become demons—a soul overcome with jealousy might actually take leave of its body, flow out over the world, and possess or haunt the object of jealousy or longing. While few characters in Genji Monogatari qualify as simple “antagonists”—the novel’s too subtle for that—one constant menace is the Rokujo Lady, who was betrayed by Genji in his youth, and never forgot him. She doesn’t plot revenge like a Child ballad villain. Her soul merely takes leave of her body to make life living hell for Genji and his paramours, two of whom die in the process.

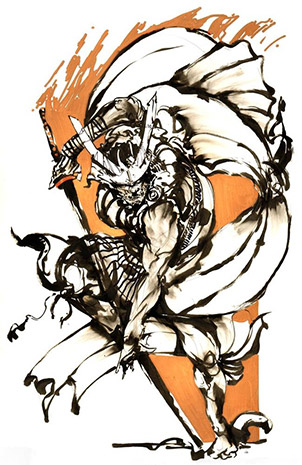

“The Duel” by Jason Scheier

Ghosts and demons and gods are edge cases of Genji’s reality, but they’re not any less real than the people he encounters on a day to day basis.

The best part about this is that the novel never bothers to explain what’s going on. Demonic possession is referred to as such, and ghosts are identified when they appear—but readers are left to deduce the pattern, and its connection to the Rokujo Lady, on their own. These happenings are unexplained, but they’re not treated as explicitly supernatural within the narrative, since we’re talking about a time before Enlightenment nature-supernature distinctions arose. Ghosts and demons and gods are edge cases of Genji’s reality, but they’re not any less real than the people he encounters on a day to day basis.

While the ghosts and the like are a sideline to the Genji Monogatari‘s romantic plots, they’re a great examples of two concepts key to modern fantasy: first, worldbuilding through glimpses, that skill which so distinguishes the fiction of Roger Zelazny, John M. Ford, and Gene Wolfe. People who exist in a fantastical setting and tell stories there don’t bother to call out their setting’s fantasticality; we the readers are left up to our own devices to determine that, to take an example from Wolfe, a destrier isn’t just a big horse, but a big sharp-toothed armorplated horse that hits 60 mph at a gallop.

The second concept is that the fantastical does not seem fantastical to locals. Genji’s reaction to a ghost, or to a demonic possession, is not the Lovecraftian narrator’s “THAT IS UNPOSSIBLE” followed by a prolonged paragraph on circles of firelight, mad dancing beyond the edges of reality, etc., so much as “HOLY SHIT, GHOST!” He—and the other people in his world—are afraid of ghosts because they are dangerous and terrifying, not because they represent a hole in a world system that does not incorporate them.

Don’t come to The Tale of Genji for swordfights and magical struggles with ancient evil, but if your taste runs to the subtle—if you’re fascinated by court politics, by love and loss, prophecy and dream, ghosts and spirits and duels of poetry—if the court chapters of Tigana were your particular poison—then do yourself a favor. Find a copy of Genji, and on an appropriately rainy day, sit down to read.

Destroying Fantasy Special Edition

The Tale of Genji has a very strong claim to the title of “world’s first novel.” It was written by a woman, in the vernacular of her time, while contemporary “high art” tended to be written in Chinese. It was distributed one chapter at a time, and historically each page has featured a detailed illustration, with dialogue bubbles. Oh, and since all this is happening before “industry” as commonly conceived, she’s basically self-publishing this book.

Meanwhile, contemporary Northern Europe was basically full of Vikings and fire.2

Finding Genji

We’re blessed in having an excellent current translation by Royall Tyler. Tyler’s language is beautiful, and / but he preserves an aspect of the original language that some might find confusing: its tendency to refer to key figures by title or by some significant detail rather than by name (think “the Breaker of Horses” rather than “Hector”). In fact, most characters are never referred to by name, and their appellations change over time as they move, gain new titles, and fall in and out of love. Tyler, thankfully, includes a short introduction to each chapter listing the most common appellations for the characters. If you find yourself struggling still, take heart: earlier translations, while still good, tend to gloss over this allusive element of the text and just refer to everyone by their critically-determined name all the time.

As for adaptations, those are harder to track down, partly due to the enormous and discursive nature of the novel: adapting it would be like adapting Proust. (Also, while the book is hardly Jin Ping Mei, the centrality of sex to the plot means that it’s easy for adaptations to, well, “descend” is editorializing a bit, but let’s just say they can veer in a porny direction.) If you’re interested in a shorter introduction to Heian Japan, though, so you can hit the ground running, may I recommend:

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon — Everyone should read this at least once in their life. A Pillow Book was a diary kept under the pillow, for recording random thoughts—as often lists or snatches of poetry or ruminations on a theme as tales of daily life. Basically, this is the Tumblr of a noblewoman from 10th century Japan, complete with reaction gifs, and it is AMAZING. What are you still doing here? Go read!

The Diary of Lady Murasaki — This is the diary of Genji Monogatari‘s author, or at least appears to be; some scholarship was inconclusive on this point when last I checked. It’s more narrative than the Pillow Book, which is both good and bad—you get more of a sense of what people were doing in this world, but reading the Diary, I miss Sei’s lists and antics.

The World of the Shining Prince — Ivan Morris, gifted and brilliant scholar and translator, realized some of his students were bouncing off Genji Monogatari like a wren off Neal Stephenson’s patio door, and so wrote this detailed introduction to the world and its customs. This book is basically a statblockless sourcebook for roleplaying in Heian Japan, exhaustively researched and carefully developed. It’s mid-century scholarship, so watch out for various pitfalls and essentialist assumptions—but it’s good mid-century scholarship, so there aren’t many.

1 NB: This sidebar was inspired heavily by Rothfuss’s Guest of Honor speech at Vericon, of which I wish I had a recording—he spun an audience question into a great ten minute riff on science, epistemology, and worldbuilding along these lines.

2 Yes, my medievalist friends, I know there was more going on in the late 10th and early 11th centuries than Vikings and fire. But come on. Murasaki wrote The Tale of Genji when Western poets and illuminators were writing the first version of the Song of Roland and composing the Domesday Book. Both of which are awesome. But still.

So a self published fantasy novel, written by a woman, influential for centuries afterwards. “Women destroy fantasy” indeed! ;)

Excellent article! I live in Japan so I’ve been familiar with the title, but never investigated it. So…now I’ll have to investigate it. I should probably look under my Japanese wife’s pillow and see if I can uncover any interesting ruminations.

[…] Gladstone’s Broader Fantasy Foundations series on A Dribble of Ink has a new installment about The Tale of […]

Great article! Genji’s been on my to-read shelf for ages — guess I should bump it up.

And another book for your recommended reading list is “The Confessions of Lady Nijo” — the memoirs of a thirteenth-century royal-courtesan-turned-traveling-Buddhist-nun. Gorgeously written and a fascinating look at that time and society.