“I pretend I am a princess, so that I can try and behave like one.”

-Sara Crewe in A Little Princess

I had loved reading fantasy as a child, but even as an older teen I struggled to find speculative fiction that challenged me without making me feel unwelcome and unvalued.

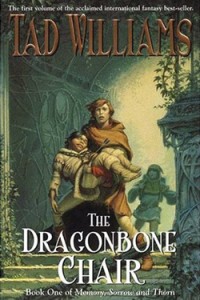

In the early oughts, I nearly gave up on epic fantasy altogether. Until I stumbled across a copy of The Dragonbone Chair at a used bookstore. I can’t quite remember why I decided to give it a chance, but I’m incredibly glad that I did. My love for Tad William’s Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn isn’t unconditional, but it did a lot to restore my faith that I could find fantasy stories that I would enjoy as an adult. I had loved reading fantasy as a child, but even as an older teen I struggled to find speculative fiction that challenged me without making me feel unwelcome and unvalued. After all, Terry Brooks may have given me Brin Ohmsford, but he also turned Amberle into a tree. It wasn’t just that the lives of the girls and women in these novels seemed to revolve around men. What bothered me more was that they rarely acted in ways that seemed logical, consistent, or grounded in anything resembling human behavior. My problem was not that Amberle sacrificed herself, but that I was never convinced it was in character for her to do so, especially as described in the book. And we won’t speak of Piers Anthony, and what it was like to read his novels, which came highly recommended, while also trying to deal with grown men yelling things about my body at me while I walked home from the library.

Art by Chaotic Muffin

I didn’t dream of being a farmer-boy-turned-king when I was younger, I dreamed of being a princess. Today, princesses often represent everything we don’t want our daughters to grow up to be: complacent, weak, frivolous, and lacking in ambition. But as a girl, the princesses that I looked up to were never any of these things – at least not to me. They were brave, like Irene from The Princess and the Goblin. Imaginative and kind, like Sara Crewe from A Little Princess. They commanded troops and were in charge of battle plans, like Mickle in the Westmark trilogy and Princess Leia in The Empire Strikes Back. They drew their pride and strength from the women who came before them, like Princess Eilonwy in The Prydain Chronicles. There’s certainly plenty to critique when it comes to princesses, the stories we tell, and how constricting these roles can be. But there’s also something to be said for including in that conversation how girls see themselves, and the role models we give them, and recognizing that this can be very different from how culture, as a whole, views girls who wear tiaras and fancy dresses.

My biggest disappointment, when I began reading epic fantasy novels marketed to adults, was not only how few women there were in these stories, nor even how much more constricted women’s roles often were compared to those I grew up reading about, but how condescending these stories often were towards girls – and princesses – in particular. I was still in my teens when I began reading The Belgariad, about the same age as Ce’Nedra when she first appears in the story. Not only was Ce’Nedra nothing like me, she wasn’t even like the popular, snobby girls at school. In contrast to well-rounded characters such as Lavinia, Sara Crewe’s jealous classmate, Ce’Nedra seemed to be made of nothing more than slander and lies about teenage girls. She came across as particularly designed to bolster male fantasies and egos, to provide excuses for Garion to shake his head and pout about girls. The fact that she was a princess made me especially angry. Like Sara Crewe, I pretended to be a princess because I wanted to be better than who I was. Pawn of Prophecy didn’t merely mock this childhood fantasy (while still supporting the very juvenile trope of the farmer boy who becomes king), it felt to me as though it was scorning the idea that girls had value at all.

Art by: Lauren K. Cannon | Cathyrox | Jen Zee

I never felt as though Williams himself thought less of girls – or forgot that girls as well as boys might be reading his books.

Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn deserves praise for many things, but at the time what meant the most to me was the way that it shows Princess Miriamele as someone who is perceptive, intelligent, and eager to do right by her people – even if she needs to grow up a bit, just as Simon does. There are a lot of parallels in the relationships between Miri and Simon and Ce’Nedra and Garion. But where Ce’Nedra acted in ways that were hard for me as a reader to believe, Miri ‘s actions were simply difficult for Simon to predict or fathom. One of the things that Williams does well, when it comes to Miri at least, is showing us her interactions with Simon in such a way that it’s clear that his perceptions of her are merely that, rather than an absolute truth. We aren’t just given Simon’s view of the situation, but also the kind of small details (such as how sad Miri looks when Simon realizes she’s a princess) that allow us to make our own assessment about what she might be thinking and feeling. I may have wanted to shake Simon silly a few times (who didn’t?) but I never felt as though Williams himself thought less of girls – or forgot that girls as well as boys might be reading his books.

Art by Riiick

We see this same dynamic again in Simon and Jiriki’s interactions with Aditu. Simon is clearly overwhelmed by her company, but he’s also now mature enough to realize this and not blame her for it, even if he can’t always refrain from acting as if it’s her fault. We also get to see how Jiriki behaves towards his sister, and contrast Simon’s awkward admiration of Aditu with the way Jiriki treats her with familiarity and respect. It’s important to the story that Simon be uncomfortable around Aditu and that Aditu be shown as someone who is interesting in her own right, who has adult relationships with other people, and who is a warrior and noble with power and influence. She’s more than a prize Simon can never have; in fact, the narrative makes it clear that her interactions with Simon are a very tiny fraction of her own tale.

Even the story of Maegwin is one of a princess struggling to keep her people together and safe, despite her own grief and increasingly tenuous grip on reality. She may get left behind as her father and brothers and knight in shining armor ride off into battle, and her ending is so far from happy that it left me sobbing, but she’s hardly one to sit and do nothing. Wielding a sword is not the only way to fight battles, and Maegwin is stubborn and determined. Even more than Miriamele, I could see that Maegwin was desperately trying to be the princess her people needed her to be, and the part of me that reread my copy of a A Little Princess until it fell apart ached for her.

Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn is not perfect when it comes to female characters – I wouldn’t mind having a few words with Mr. Williams about Vorzheva, and how she’s characterized, for starters – but it is full of a great many of them, all complex and unique. It was also, to me, a breath of fresh air. While plenty of epic fantasy sagas that I would later read and love had been published in the 1980s and 1990s, that doesn’t mean that they were easy to find, promoted in bookstores, or included in suggested reading lists. And while the internet existed in 2001, I hadn’t yet stumbled across the parts of it that were talking about the works of Kate Elliott or Rosemary Kirstein. At the time, it felt to me as though the adult portion of the fantasy genre was more often than not a little confused about what the combination of “adult” and “fantasy” should mean, in terms of speculative fiction, and I wasn’t at all certain that this brave new world was anything that I was interested in. Reading The Dragonbone Chair, and the rest of the trilogy, took me back to what it felt like to read The Black Cauldron, The Beggar Queen, and The Princess and Curdie for the first time. Only much more complex and mature. For that, I will always be thankful.

Really nice piece, It’s kind of embarrassing how many of these books I haven’t read, but I pretty much gave up on fantasy some time ago. I think I’ll have to read The Dragonbone Chair!

@stevenMLOng –The best news is that Tad is returning to this series and writing more in this world, which I look forward to, eagerly.

Aditu sounds like a fascinating character. She has her depth, her history, her mystery, and very little time for fools. They dynamic of an unreachable heroine is not one often portrayed in a story featuring a male protagonist, and that sounds waterfall-shower refreshing.

Certainly there’s much to be critical of in the portrayal of women in G.R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones, but I did like how he portrayed two Stark “princesses” with wildly different tastes. One loves swords, one loves embroidery, and neither apologizes for it.

Sadly, I didn’t find these books until the early 2000s, but, looking back, I think it was very important for me as a young teenage male to encounter characters like Mickle and Princess Eilonwy.

Jenny,

I really enjoyed your discussion of several of the main women of MS&T. Can you explain more about the problems you had with Vorzheva’s characterization? I always thought she was just ‘drawn differently’ than Miriamele, Aditu, and Maegwin, who themselves are each very different from each other.

Also, incidentally, have you read “The Burning Man”, Tad’s short story set in Osten Ard? It features a girl named Breda, about the same age as Miriamele. Your thoughts on her would be appreciated as well.

[…] Thurman has posted a new analysis of royal female characters in Osten Ard, from the perspective of a reader who happens to be female. The analysis covers Miriamele, daughter […]

This is a really good analysis of some of the more important women of “Memory, Sorrow and Thorn”. I particularly like the discussion of Miriamele and Aditu. Miriamele may be one of the most complex teenage girls ever depicted in fantasy literature. And Aditu, though a vastly different character, is also written quite well, with complex dynamics that aren’t easy to comprehend, due to her ‘alienness’. It’s hard to understand Aditu’s motivations and thought processes, although it’s clear that that isn’t because she’s female, but because she is not human. Tad Williams writes both characters in an interesting way, although they are completely different. They also both pass the Bechdel Test.