“Come close, my friends, and know that in our tale as in the world, anything may happen.”

pp. 111

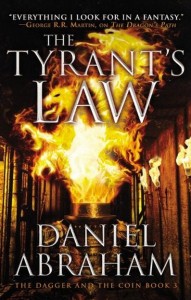

“Anything may happen.” This phrase, more than any other, exposes the heart of speculative fiction. Removed from the accepted and understood restrictions enforced by a real world setting, speculative fiction is allowed to explore themes, ideas and conflicts that might not naturally intersect in the more restrictive boundaries of traditional literature. This speculative playground is even more powerful when it is used to create a world, and fill it with conflicts and themes, that raise questions of issues that readers ask themselves about our own world. Few in-progress epic fantasy series do this as well as Daniel Abraham’s The Dagger and the Coin, further proved by its third volume, The Tyrant’s Law.

Speculative Fiction is allowed to explore themes, ideas and conflicts that might not naturally intersect in more traditional literature that has more restrictive boundaries to play within.

Though The Dagger and the Coin is set in a familiar European-inspired world, it sidesteps the pitfalls that plague so many of the genre’s endlessly bland and derivative works. By asking the right questions, and by building a world through a hard-nosed perspective that demands respect for the challenges present within ethnically diverse groups of people, The Dagger and the Coin allows Abraham to draw on the genre’s best tropes, while avoiding its most prominent failings, mainly homogenization and a lack of courage. Anyone, regardless of their ethnic background, or socioeconomic place in the world, will find something, or someone, that resonates with them in The Dagger and the Coin.

The Tyrant’s Law, the third volume in a five volume series, is plagued by the same issues often criticized in middle volumes of many fantasy series, such as an un-satisfying feeling of the story lacking a true beginning-middle-end structure (there’s mostly a lot of middle), and the awkward problem of having to juggle the timelines of several different characters and stories at a consistent rhythm (ensuring that nobody gets left behind.) It helps that the novel takes place over a large span of time (several months), but it is sometimes awkward to measure progress on a travelogue-style plot against a stationary, slow-burn political plot in a city, especially when screen time among characters is about even. Moreso than in the previous volumes, it feels like some of the characters, Cithrin in particular, might have benefitted from increased screen time, even if it meant lessened screen time for other characters. After waiting for a year to return to this world, The Tyrant’s Law feels in some ways like nothing more than a fleeting moment between friends, rather than a proper reunion.

Like those aforementioned middle volumes, it is difficult to accurately judge the standing of The Tyrant’s Law and its overall successes and failures while lacking full understanding of its context within the overall series. Judged on its own, The Tyrant’s Law is frustrating for asking more questions than it answers (and those that it does answer, such as the fallout from a major betrayal in The King’s Blood, play out in somewhat anti-climatic manner). The endings for each character make big promises for the fourth volume, The Widow’s House, but the waters seem muddier than ever, and the road to victory out of sight. Judgement on whether these promises pay off will need to be witheld until the final volume is released. At times, it can be difficult to tell exactly what everyone is fighting for/against in the grand scheme of the series. This, however, is only an attempt at framing The Dagger and the Coin in a way that is familiar, rather than allowing it to take its own path to the finish line, to carved its own path through the story. In a series that embraces so many genre tropes, it’s easy, but unfair, to expect it to follow a familiar plot structure. Despite these pacing issues, forgiveness can be given because it feels so good to be returned to this world, and to step in alongside ‘friends’ (even Geder), however fleetingly.

Thematically, Abraham continues to explore religion, clashing culture/society, and the mass manipulation of groups of people by individuals (or small groups) with motives of world-spanning power. One particular passage catches many of these themes into a few short lines,

Marcus saw himself reflected in the vast amber depths of it. He wanted nothing more than to run. There was no sense of threat from the vast eye. No malice. Only a danger as deep and profound as religion.

pp. 474-475

Even in his near sociopathic state, Geder raises a good question, one that Abraham is, layer-by-layer, attempting to answer:

“That can’t be right, can it?” Geder said.

Basrahip raised querying eyebrows.

“The three-year fire,” Geder explained. “A fire that went on that long would have left a layer of ash all over the world. And there are cities that stood where they are now since before the dragons fell.”

“If it must be, it must be,” Basrahip said. “But the fire years are truth.”

“But there are forests in Northcoast that have trees older than that. Not many, maybe, but I read an essay about how you can tell the age of a tree by the number of rings, and it said the largest of the redwoods in Northcoast—”

Basrahip shook his bull-wide head.

“You put too much faith in empty words. No forests live that were not planted after the fire years. All animals that live were sheltered by humanity in the fire years. If you say that the world must be built upon ash, then look for it, and you will find it. Or if you do not, you must find for yourself what became of it. But the fire is true.”

“It’s just in all the histories I’ve read—even the ones written within a generation or two of the fall—no one’s ever mentioned a catastrophe like that. You’d think they would have. I mean, the utter destruction of everything’s not the sort of thing I’d leave out if I were writing a history.”

pp. 28-29

The dogmatic and sometimes cult-like behaviour of extreme religious sects is right at the core of this series. It dictates and shapes many of the core conflicts being faced by the various characters who are trying to navigate through its war-torn pages, and, through the lines-in-the-sand often drawn by zealots and mad, power hungry people who use religion as a weapon, Abraham is able to create a world that is experiencing many of the same crises that we see reflected in our own world’s insecurities, reported nightly on the six o’clock news. In discussing The King’s Blood, I inspected Abraham’s purpose for building a world populated by so many different races, so different and yet so similar, and what that meant in the overall conflict nested in the conflict between the Dragons and the Spider Goddess. I said:

Like our own world, which is populated by billions of people, some of whom are tall, some short, some have dark skin, some have light, some an epithantic fold to their eye and black hair, others blue eyed with pin-straight hair the colour of hay. But they are all humans just the same, irregardless of race. I can hear a story about fellow humans, something funny or sad, something true or something fictional, and never once stop the person telling the story to stop and describe, at length and with specificity, what ethnicity these characters are, what colour their skin, or whether they had brown eyes or blue. In some cases, cultural tendencies might have an effect on the context of the story, but often not. Generally, none of it matters a lick to the story being told. So, what does it matter if a character in Abraham’s series has glowing eyes, porcelain skin, or walrus-like tusks growing from their mouth? As Abraham’s characters are wont to point out, the thirteen races of humanity all spawn from a single starting point and, despite their differences, and their own set of racial standards and prejudices, are all just humans. They are characters, and when I stopped trying to define them visually or pigeonhole them for being Timzinae, Firstblood or Kurtadam, I was able to fall further into the story.

“Being conquered is sometimes uncomfortable,” Ternigan said, and the issue was dismissed. p. 68

In this later volume, this picture begins to clear somewhat and readers, along with the characters, learn, slowly, that the war being fought in the present is little more than an extension of a war fought hundreds or thousands of years earlier by preternatural forces, and the divide among the thirteen races was, perhaps, once manufactured and manipulated for the purposes of those waging that long-ago war. My assumption above, that all the races were created equally, is called into question in The Tyrant’s Law and continues to add a level of thematic depth lacking in many series similar to The Dagger and the Coin. It’s easy to enjoy this series for its surface level success — characters, adventure, language — but, it’s even more satisfying to consider some of the questions that Abraham is asking between the lines.

Of the characters, Geder, and his maniacal decision-making, continues to be a core strength of the series as Abraham carefully pieces together the building blocks of a tyrant with the best of intentions. Marcus continues to follow the most archetypical ‘fantasy’ plot, his travelogue-like quest to find a magic sword taking him deep into a treacherous land. Cithrin takes a bit more of a back seat, at least early in the novel, as control over her place in the world is taken from her, but she makes one decision, right at the end of the novel, which is certain to send ripples of chaos through the world over the course of the final two volumes. Most interesting to me, again, is the story of Clara Kalliam, disgraced wife of the late Dawson Kalliam, who was a viewpoint character in earlier volumes. Her fall from grace as a result of her husband’s death was swift, and there’s a terrific resilience in Clara as she discovers that though her traditional place of authority has been stripped from her, a truer power has replaced it: freedom. Her ghostlike attack against Geder Palliako and the Severed Throne, along with a budding romance with a young man who represents all the strengths and virtues she needs to succeed, is masterfully handled by Abraham and a joy to read.

Of the characters, Geder, and his maniacal decision-making, continues to be a core strength of the series as Abraham carefully pieces together the building blocks of a tyrant with the best of intentions. Marcus continues to follow the most archetypical ‘fantasy’ plot, his travelogue-like quest to find a magic sword taking him deep into a treacherous land. Cithrin takes a bit more of a back seat, at least early in the novel, as control over her place in the world is taken from her, but she makes one decision, right at the end of the novel, which is certain to send ripples of chaos through the world over the course of the final two volumes. Most interesting to me, again, is the story of Clara Kalliam, disgraced wife of the late Dawson Kalliam, who was a viewpoint character in earlier volumes. Her fall from grace as a result of her husband’s death was swift, and there’s a terrific resilience in Clara as she discovers that though her traditional place of authority has been stripped from her, a truer power has replaced it: freedom. Her ghostlike attack against Geder Palliako and the Severed Throne, along with a budding romance with a young man who represents all the strengths and virtues she needs to succeed, is masterfully handled by Abraham and a joy to read.

In many ways, there’s little in terms of direct conflict for the characters, and least in the physical sense. Most of the novel’s breaking points happen internally, as each of the characters confront themselves and struggle to figure out their place in an ever more tumultuous world. Those looking for something big and explosive might look elsewhere; but, then, if such is the case, you’re reading Abraham for the wrong reasons. Anyone who has grown to love these characters will feel genuine empathy and sympathy for them as they are faced with increasingly difficult decisions, now often directly affecting one another as the outcomes of those decisions play out. It’s difficult as a reader to watch the fallout of one favourite character’s decision harm another.

The Tyrant’s Law is a fine addition to one of Fantasy’s strongest series.

If you’ve read this far, you know what to expect from The Dagger and the Coin: terrific characters, strong and intelligent thematic roots, and silky-smooth prose. The Tyrant’s Law might plod along like a middle book, but the characters are so familiar, the world so interesting to explore, and the story so engaging that any of my frustrations can be blamed on having to wait another year to continue the story. Daniel Abraham continues to write quality novels that feel familiar and yet entirely unique at the same time, and The Tyrant’s Law is a fine addition to one of fantasy’s strongest series.

As mentioned on Twitter and elsewhere, a lot of readers, I think,. identify strongly with Geder. And then there are plenty of other role models and things for other types. Heroic Types. Strong female characters. Interesting worldbuilding. I had wondered, going in, if this was going to be “more ordinary” than the Long Price Quartet.

It is more ordinary…and it isn’t.

I can’t wait to read this one.

Exceptional review Aidan. I think we both agree that Clara might be the standout character in this volume.

Even if Cithrin didn’t get as much screen time, what she did get will likely have at least as great and maybe a greater effect on the world and the other characters than some of the actions of the other characters.

“In many ways, there’s little in terms of direct conflict for the characters, and least in the physical sense. ”

Fair point, but this didn’t bother me in the least. I felt the very character driven nature of this installment was its strength.

(BTW, where’d you get the cool dragon image?”

@Paul — As I mention in the review, I think that ability for many people across various backgrounds to find someone to connect with is one of the strengths of the series. That Geder, who makes some truly awful decisions in this novel, is one of them is astounding testament to Abraham’s ability to empathy build.

@Rob B — Thanks. I really appreciate the kind words. I think you’re right about Cithrin’s decision, I just yearn, because I’m a greedy reader, for more time spent with her and Isadau. I also agree that the character-drive/internal conflict of this novel is one of the series’ high points. Intense stuff to watch as a reader.

The dragon illustration is a piece of concept art from Guild Wars 2. I believe (though don’t quote me on this) that the artist is Daniel Dociu, who also does the cover art for Abraham’s (Corey’s) Expanse series.

It was maybe more obvious with The Dragon’s Path than in The King’s Blood, but this series generally seems to be more quiet and subtle than other epic fantasies, and also more character driven. There are Battles and Badasses (B&B), but that’s not really the point of them. I keep coming back to this series because I love the characters.

(Also: I hope that first excerpt means the Carrie’s Players will be back, even though Kit is no longer with them! They are always so much fun!)

Anyway, great review, Aidan. Really looking forward to this.

Thanks, Dave.

You’re right that the ‘B&B’ serves less as a centrepiece to snag readers and more as a tool to force the characters into difficult situations that, through desperation, force them to confront themselves. It is a nice subversion of the general trope-grab used by a lot of genre novels. Same elements, different conflicts, solutions and outcomes.

(Also: I won’t spoil anything, but, well, you might just be in for a treat.)