Here at A Dribble of Ink, given that Aidan Moher and Kate Elliott are currently two posts in to their joint reading and analysis of Daggerspell, book one in Katharine Kerr’s fifteen-volume Deverry saga, it seems like a pertinent time to review Kerr’s latest novel, Sorcerer’s Luck – not only because it’s a refreshing, enjoyable read in its own right, but because it serves as a solid introduction to Kerr’s thematic style. Which is a useful thing to have to hand: as much as Deverry constitutes one of my absolute favourite series of all time (and for anyone interested in some of my slightly spoilerish thoughts on same, they can be found here), even though the series is finished, fifteen books is a lot to ask anyone to invest in without some proof that they’ll enjoy the author’s writing. This is, for instance, the big problem with recommending Terry Pratchett’s Discworld to first-time readers: whichever book we might personally view as the apex of the series (mine is Night Watch), a big part of our love for it invariably comes from the fact that we already know the characters from earlier stories. I was, therefore, immensely pleased when Pratchett went and wrote Nation, an incredibly powerful book that not only exemplifies the best of his style, but which neatly cuts through the issue of recommending any one Discworld novel as a starting point.

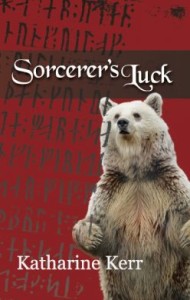

Which brings me back to Sorcerer’s Luck: a story about the relationship between Maya Cantescu, a struggling art student and vampire-but-not-really based in San Francisco, and Tor Thorlaksson, a wealthy sorcerer and bjarki – that is, someone who shapeshifts into a bear. Among her other talents, Maya has the ability to see through illusions, and when Tor finds himself being haunted at the dark of the moon by otherworldly manifestations, he hires Maya to see through them. But their professional relationship soon becomes complicated, not only by their mutual attraction to one another, but by the increasingly violent actions of Tor’s sorcerous enemy. What’s the real reason for Maya and Tor’s connection? And what does Tor’s unknown opponent want?

Given the overwhelming abundance of romantically-oriented vampire and shapeshifter stories on offer, I’ll completely understand if, somewhere during the previous paragraph, you rolled your eyes.

Given the overwhelming abundance of romantically-oriented vampire and shapeshifter stories on offer, I’ll completely understand if, somewhere during the previous paragraph, you rolled your eyes and thought, however briefly, Oh, great. Another one. It’s an understandable reaction to have: however much we might love a particular combination of narrative devices or SFFnal tropes, and regardless of the very important distinction between the stories whose use of said elements we find captivating and original rather than generic and derivative, there’s a certain amount of exhaustion that invariably accompanies the process of sorting out which is which. With that in mind, then, let me be clear from the outset: Sorcerer’s Luck stands firmly in the former category. One of Kerr’s greatest strengths as a writer – and in fact, I might go so far as to call it her signature strength – is her ability to subvert the established norms of genre and subgenre simply by turning her hand at them. No matter the differences in time, place and motive that separate her various novels, they’re always united by an exquisitely deft sense of location, era and personality, because Kerr is one of those incredibly rare writers whose worlds never feel constructed, but rather discovered.

Sorcerer’s Luck is no exception. Though the system of runes, bindings and illusions used by Tor is both engaging and believable, the plot constructed around just the right balance of external action and internal conflict, and the core mystery neither overly simple nor needlessly ornate, the real heart of the story lies in the characterisation. As the story begins, Maya, a WOC, is living in a form of near-poverty that’s all too familiar in the current economic climate. As well as running herself ragged working long shifts at a burger-flipping job to support herself through college, she puts up with her tiny, scummy flat while simultaneously juggling student loan debt, credit card debt and, as an added supernatural bonus, the stress induced by living with vampirism. Not that Maya craves blood: she doesn’t even get the benefit of being immortal. Instead, she needs to drain the life-force of living people – élan – in order to stay alive. Her condition is genetic, and in a twist that mirrors her financial insecurities, Maya has to scrape by in this regard, too: instead of draining individuals, which would kill them, she lives on scraps of élan gleaned from healthy strangers in crowds, leaving her constantly fearful of the possibility that one day, she won’t be able to find enough, and will wither and die.

Art by Lupercos

Tor, by contrast, is incredibly wealthy. Though living under an emotional cloud thanks to a combination of family problems, his bjarki state and the frightening illusions sent to dog his home, he is nonetheless able to offer Maya the sort of stability and support – emotionally, magically and financially – that she’s been struggling without her whole life. But Maya is wary: not only because she fears the deeper association with magic that being with Tor will bring, but because she’s acutely aware of the financial imbalance between them. Tor is generous to a fault in terms of what he offers her, but Maya neither wants to be seen as mercenary, nor does she want to be in his debt – and she especially doesn’t want either concern to colour their relationship. So when it’s suggested that her connection to Tor has its roots in a past life, everything Maya thinks she knows and wants is thrown into turmoil. Can she trust Tor? Are her feelings her own? And how much will she have to compromise in order to find out?

Bound together through history by an intricate chain of Wyrd.

For anyone familiar, not only with the Deverry cycle, but Kerr’s more recent quartet of Nola O’Grady books – an urban fantasy series that puts core SF concepts like parallel worlds and alien civilisations alongside psychic powers and shapeshifting, all neatly embroidered against a crime-procedural backdrop – Sorcerer’s Luck is, thematically speaking, an interesting mix of the two. Tor’s runecasting and Icelandic heritage are contextualised by his belief in Wyrd, a type of fate or destiny that guides individuals through various lives – and which, coincidentally, is also of tantamount importance to Kerr’s Deverry novels, where the endlessly-reincarnating characters are bound together through history by an intricate chain of Wyrd. Similarly, just as Nola O’Grady uses the power of chi to fuel her psychic abilities, so does Maya use chi (or élan, as she more often calls it) to stay alive; the same substance, in fact, that Tor requires for shapeshifting.

And then there’s the family element, which is another common theme across Kerr’s work. Whereas many urban fantasy heroes and heroines are either portrayed as only children, orphans, or as otherwise being estranged from what little family they have left, Kerr’s characters are enriched by their familial relationships. Though some of these relationships are purely supportive, just as some are purely destructive, the vast majority are just lovingly complicated in a way that’s immediately recognisable – and all portrayed with a grounded, plausible honesty that SFF, with its tendency towards big drama and magical contrivances, seldom manages. In Sorcerer’s Luck, this comes courtesy of Maya’s brother, Roman, a war vet whose drug addiction forces her to evaluate all their interactions through the lens of how likely he is to be lying to her. Neither is Kerr’s definition of family restricted to blood-connections, either: both Maya and Tor have healthy, active friendships that influence the story, avoiding the trap of urban fantasy characters with predominantly dysfunctional – or in some cases, non-existent – relationships.

Kerr’s characters are critical: by thinking through their own decisions and asking questions of events, they force us to treat the narrative likewise.

In short, Kerr’s characters are complicated, flawed, and very, very human, regardless of their magical abilities, which are never used as a get out of jail free card when it comes to unacceptable behaviour. Which isn’t to say that her characters never slip up or misbehave: they do, and sometimes badly. They have biases, tempers, bad habits, foibles and addictions; and some, invariably, use problematic language or present problematic attitudes. This latter is particularly important, because while such traits are extremely realistic, it’s very easy to present them uncritically, lazily, accidentally, or in such a way as to suggest that the author has failed to identify them as problems at all, with the result that the narrative ends up tacitly condoning them. But this is never the case with Kerr: her skill with characterisation means that nothing is there by accident. Especially when reading from the POV of a single narrator, it’s easy for readers to become complacent, excusing everything an apparently sympathetic character says or does simply because they’re viewing events either from that person’s perspective, or the perspective of a similarly unfased observer. But Kerr’s characters are critical: by thinking through their own decisions and asking questions of events, they force us to do treat the narrative likewise.

A powerful example of this comes near the end of Sorcerer’s Luck, when Maya is being given the brush-off by busy hospital staff: that is to say, by white hospital staff, who have identified Maya as an impoverished WOC and responded according to their own biases. But when Tor, a wealthy white man, arrives on the scene, everything changes: he reacts furiously to the way Maya has been treated, and instantly secures the attention of the same staff who’ve been ignoring her for hours. When challenged on his behaviour – ‘“There’s no need to be so nasty!”’, says the nurse who’s been rude to Maya – Tor replies, ‘“I’d say there was plenty of need. It’s funny how things turned around when a white guy walked in here.”’ Not only is Kerr aware of Tor’s white privilege, then, but she makes sure Tor himself is cognisant of it, thereby adding an important level of trust and respect to his relationship with Maya. Whatever other mistakes Tor might make as a consequence of his financial privilege, we know he understands the social and racial advantages he possesses that Maya doesn’t, and takes active steps to use them for good, rather than obliviously trusting them. Similarly, Maya’s concerns about her relationship with Tor are never painted as fake obstacles or as simple emotional wavering: their differences and personal histories represent real problems, and as Maya continues to evaluate what she knows about Tor, so must the reader do likewise.

If I have one complaint about Sorcerer’s Luck, it’s that it touches on more themes of interest than the novel has time to deal with in full, particularly with regard to the secondary characters. In this respect, it reads like the first book of a series without necessarily being one – I say necessarily, because I’m not sure whether Kerr is planning a sequel, or if the extra detail is simply a consequence of the native care and interest she takes in building a believable setting. In either case, though, it’s a minor issue in the scheme of things, and while Sorcerer’s Luck is perhaps smaller in its scope and ambition than Kerr’s usual fare, it nonetheless holds its own as a solid and enjoyable example of her work.

Katharine Kerr is an author whose writing I will always love and respect, and […] I’d happily recommend Sorcerer’s Luck.

And given its references to both chi and Wyrd, regardless of the actual canon, I can’t help but think of it as a bridging novel: one that suggests both Deverry and Nola O’Grady might ultimately exist within the same narrative universe. In Deverry, Kerr talks about the mother roads – paths through different, parallel worlds that are strongly implied to tie Deverry to our own, historical Earth – while Nola’s world is explicitly one of many overlapping realities. Perhaps, then, it’s more than just a passing fancy to wonder if all these stories are connected, however briefly, like different beads strung on the same necklace. Katharine Kerr is an author whose writing I will always love and respect, and if you’ve ever wondered whether you might feel similarly, given the chance, then I’d happily recommend Sorcerer’s Luck as an opportunity to find out.