[Editor’s Note: What follows is a critical essay in the traditional sense: an in-depth and spoiler-filled analysis of Ken Liu’s The Grace of Kings—focused particularly on the women in the novel. It’s thoughtful, beautiful, and important—but if you’re sensitive to spoilers, you might enjoy reading it more after you’ve completed Liu’s epic novel. If you’re looking for an (almost) spoiler-free review to help you determine whether to buy it, let me suggest Justin Landon’s review on Tor.com.]

Many months ago Joe Monti, editor of Saga Press, Simon & Schuster’s SFF imprint, sent me a copy out of the blue of Ken Liu’s The Grace of Kings for a possible quote. More precisely, and using the proper polite etiquette, he contacted my editor at Orbit who forwarded his email to me.

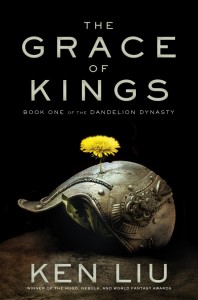

I knew Ken’s name, of course. He’s a multiple award winner (Hugo, Nebula, World Fantasy) for his short fiction. He has also done an important service to the sff field by translating short fiction and novels from Chinese into English, works that readers in the English-speaking market would not otherwise be able to enjoy. The Grace of Kings is Liu’s debut novel.

My Intent

In this post I’m going to do something I rarely do: I’m going to reveal my thought process about how I read this novel, and because some of it will come across as critical I’m stating right up front that I loved this novel.

It is beautifully and intelligently written. It’s a great story about the process of history and politics that includes memorable characters, fantastic world-building and invention, and an adept use of structure that melds Western epic traditions with the Chinese tradition of multi-layered narratives like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Our field likes to talk about novels or series that “redefine” the genre or are “bold and edgy” or “innovative.” After 26 years in the field I can say that often I do not agree with that assessment because usually there were others who did the same or similar thing earlier but did not have the popularity or readability or critical visibility to be granted the imprimatur of being a genre-defining book.

The Grace of Kings is genuinely innovative as a template for modern commercial epic fantasy.

So I will go out on a limb and state that I believe The Grace of Kings is genuinely innovative as a template for modern commercial epic fantasy. It does its thing in a way that blends epic sensibilities, and it does so from the perspective of a creator who has grown up within multiple traditions and thus has a unique ability to weave both together in a completely organic and persuasive way. (I’m seeing this blend done very well by other writers also, of course, but that’s a topic for another post.)

[Author’s note: I read a manuscript file and thus there may have been changes to the final published copy, so if I reference things that have been altered, I apologize.]

I Start Reading

However I had no particular expectations, only hope, when I began reading and immediately got hit with a strange doubled sense of consciousness. The opening scene in which an emperor takes part in a triumphal procession as a man on a kite attempts to assassinate him is exciting and fabulous (kites recur in the story) while meanwhile in the emperor’s procession there exists a float with sexy dancing girls.

I mean. Seriously. Sexy dancing girls in a society I have as yet no reason to believe encourages or tolerates excessive public displays of sexuality.

I actually stopped dead in my reading and thought, “How can this be? I can’t just have read that dreadful cliché in a story by a writer I know thinks about these things and yet here it is, a cheap and easy detail of the kind that litters the ground of so much unimaginative epic fantasy . . . even my own in places, I succumb to this cliché too, so let’s not be too judgmental here, okay? It could just be a fluke and not a harbinger of terrible unthought-through gender roles to come. It could mean something else.”

Art by Frank Hong

So I kept reading.

It took me about 50 pages to get my reading protocols fully adjusted to how Liu uses different layers and types of narrative rather than a straight third person viewpoint. The gods provide a “Greek chorus” giving us a lofty (but squabbling) omniscient view of the action. The main characters’ through-story anchors the structure. Within these weave smaller and often finite short threads in which we get all the background on and then the main events of and denouement in the lives of specific minor characters whose fates intersect the main story, which, we come to see, is in this first book the story of how a corrupt but extremely powerful conquering emperor and his court can be brought down and replaced by other, possibly (or possibly not) worthier people.

A couple of points:

-

Liu never backs away from revealing the dreadful misery and carnage that accompanies such upheavals, both in terms of the larger effects on the population and the specific effects on individuals.

-

He also does not pretend there is a simplistic and exceptionalist answer to questions of governance and rebellion. No character is fully good or right, and I’m not sure any is fully bad as we catch glimpses into what drives people to the actions they take.

-

He occasionally pauses for exchanges of philosophic conversation in a way totally appropriate to the aesthetic of the text. Likewise he is a skilled enough writer that these abstract interludes are interesting and never boring or slow.

-

There are a lot of characters. Even I—champion of the cast of thousands—had moments of getting confused, but the narrative structure and the omniscient viewpoint through which it is all told specifically work to make it possible for Liu-as-narrator to drop down to explain things to us when we need explanation in a way that third person limited or first person would not gracefully allow.

-

This is a fantastic example of a story told using the omniscient viewpoint, a technique hard to pull off and not nearly as popular as it was, say, a hundred years ago (third person limited being a relatively recent phenomenon). Liu head-hops with abandon, and it works because the omniscient viewpoint is firmly established from the beginning.

The Wimminz

Yet by 30% in I realized with a sense of creeping sadness that this was a dude story, set in a rigidly patriarchal world.

Yet by 30% in I realized with a sense of creeping sadness that this was a dude story, set in a rigidly patriarchal world. Main character Kuni Garu’s wife Jia Matiza is OBVIOUSLY smarter and more capable than he is and yet we only catch glimpses of her and then only as she acts as a help-meet to his story. Somewhat later one of the minor character short stories sets up the story of Princess Kikomi, who uses beauty, sex, and death to save her people from imperial retaliation, a story that makes complete sense in the context of the society’s mores and which is vividly told in a way I totally could see unfolding on screen as part of a multi-season tv drama. But because Kikomi and Jia are basically the only two women who appear within the plot up to that point it felt discouraging.

And yet.

I have read hundreds of novels over the course of my life in which there are no significant women characters. It’s no wonder women have flocked to read, and write, Urban Fantasy and Young Adult these days, which far more often center women in important roles. Really, I can’t say this enough: Whenever some guy complains that (for example) “all romances are the same,” I roll my eyes because so many of the books I have read are to all intents and purposes a re-tread of the same boy-coming-of-age or man-fighting-the-system or father-son-conflict or war buddies story, and so on. Yet these stories are never seen as intrinsically repetitive even when the tropes and emotions and plot structure are the same. Each one is individual! Unlike those repetitive romances!

It’s not that I don’t like stories about men.

I LOVE STORIES ABOUT MEN. SOME OF MY BEST CHARACTERS ARE MEN.

It’s just I have read so so so many and I am so so so tired of reading—and viewing—what begin to feel to me like the same thing over and over and over again. This is why (except for Season 2) the TV show Justified—well written, well filmed, well acted—bores me: It often seems like a series of dialogues between men (in different combinations) that are supposed to be profound and difficult and edgy and, you know, I’ve seen every single one of them before, multiple times. I’ve seen it already. I’ve read it already.

As I pondered these deep thoughts, I realized that actually what I really wanted was to stop thinking about the issue of gender and get back to reading The Grace of Kings . . . because I WANTED TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENED NEXT.

Art by Xu Xinmin

The skill, story, emotion, and characters of the story had drawn me in. The narrative was fascinating because it was well done and furthermore because it was not being told with the same repetitive tropes and rhythms as is so much fiction I run into. I was enjoying it in the same way I love The Wire, a brilliant television show that focuses intensively on men and does not do particularly well by its female characters with the exception of Season 4. I consider The Wire one of the most complex and insightful narratives I have ever seen on tv . . . even considering how it scants the role of women in a modern society.

Many stories that don’t include women in any significant way leave them out because the frame and aesthetic of the story world is unimaginative. It’s a writing flaw. Yet—and this should go without saying but unfortunately I have to say it—it is also absolutely completely possible to tell an excellent or even just fun and entertaining story in every possible iteration, with men, without men, admixed genders, and so on. Whatever Liu was doing in this book, it was working for me, which made me think about why other books don’t work for me, and what the difference in approach is: also a topic for another post.

Liu is playing a long game: He brings in women characters in a major way in the last third of the book.

As it happens, Liu is playing a long game: He brings in women characters in a major way in the last third of the book.

While many laud the martial character of Gin Mazoti—a character I very much appreciated and enjoyed—I was just as happy to see Liu also focus on women acting with agency in more traditional roles. As I have said before and will doubtless say again, as much as I love kick-ass women—and I really really do—if we as writers can only give importance to a woman character (especially in a society written to be patriarchal) when she does things that are coded as “male” in that society — that is, only if she “rises” to a societally-designated male status (as Gin does) — then we are not in fact raising the status of women overall or doing ourselves or our characters any favors.

Liu does not do that. Once he deploys women he uses them in a variety of ways and in a variety of roles and with a variety of personalities. I personally will be most interested to see how he deals in the second volume with the two vying queens: That will be a serious challenge because it is easy to fall into tired stereotypes about grasping, jealous women and hard to unfold the nuances of intelligent women trying to make their way and protect their children in a society stacked against them.

Here’s another and even more interesting thing that Liu does:

When Kuni Garu realizes he can use women to win his war precisely because his (male) enemies will not expect it or even react to it, we as readers are totally with Kuni. We don’t need a single thing explained about why this strategy will work because Liu has resolutely stuck to his patriarchal society with its focus on the men’s lives for so much of the book. He uses our own expectations of reading traditional patriarchal societies in an epic fantasy as part of the reversal he creates. When the defenders of Rima can’t defeat Gin’s smaller force because their commander not only holds to outmoded tactics but can’t believe “an ignorant girl” can lead an army, the story has already prepared us for Zato’s behavior. This element of the plot would not have worked as well if Liu hadn’t set up the nature of this patriarchal society, and the general absence of women as actors on the “public stage” of life, so patiently.

I do think Liu makes a pair of minor stumbles in this regard:

-

In Chapter Twenty-Two, The Battle of Zudi, Kuni’s stirring “I’ve seen the bravery of Xana’s women first hand” speech pretty much comes out of nowhere. What was startling wasn’t that Kuni would make such a speech as he’s the perfect person to do so within the narrative and furthermore this incident sets up his later willingness to raise Gin to a general’s rank and to listen to women in general. What was startling is that up until this moment we have barely seen any women even in the background and in fact don’t see the very women he is talking about, much less all the work they are doing, until he identifies them to the other men and thus to the reader. It jarred me at the time of reading because women had been invisible in the text before they were so suddenly called out and praised—by a man—as part of the plot. However, I must note it is possible Liu wrote it this way on purpose; that is, that he waits until Kuni gets the other male characters to see women before the reader starts to see women in any numbers, in which case I applaud his subtlety.

-

I confess I was puzzled and disappointed in some aspects of the depiction of the islanders from Tan Adü, the land of savage cannibals, who have two important set pieces in the story (the plot elements of this worked fine for me and I love the crubens). I had the feeling the islanders were meant to feel culturally different from the other peoples we meet, just as they are described as being physically distinct. I’ve read a couple of reviews that suggest there is a Polynesian element to the setting, but as a person who lives in Hawaii (although I hasten to mention that I am not Native Hawaiian) I don’t see that correspondence at all. When I read the Tan Adü parts they felt culturally disjointed because I felt I was being told one thing and shown another, right down to the unseen women of the islands literally being mentioned solely in reference to sex and food.

However, for me as a reader these proved to be minor issues within a text that bowled me over. I for one am so very very glad Ken Liu is writing this series and I eagerly anticipate the next volume.

In this review I have chosen to mostly focus on the role of women within the text, yet in a narrative this rich there are any number of vectors and tangents out of which discussions can unfold. I invite (yes, YOU!) to comment with your own observations or responses on any aspect of the novel.

Thanks for this Kate.

I admit that I, too, saw his world as being rather traditional in handling women’s roles, which didn’t disappoint me quite so much, since I was distracted by other things. (Another novel I won’t name I read last year that was far more traditional DID annoy me in this regard). When that last third does kick in, you’re right, I saw the “long game” that Ken is playing. This is not a one and done, he’s writing a series.

There is a real theme of “going to the future” that is uncommon in epic fantasy. The best years aren’t behind us, they are still to come and we can get there. We can change and adapt and invent our way there. And part of that in this novel is *culture*, especially in the roles of women. It seems to be that a more equitable role for women is being invented in the culture, as we read and watch it.

Enjoyed this post, loved Grace of Kings, and also had some problems with the portrayal of women. I think I had it easier because while I was trying to avoid spoilers going in, it seemed everyone in my twitter feed was reading & exclaiming over this book and particularly that it was trying to subvert and challenge existing tropes

With those lenses on, it was easy for me to read the opening parade as an exotic parade of marvels specifically to bring the reader into that world but so over-the-top I didn’t expect the exoticism to continue. I mostly felt that the “calling attention to and subverting” tropes continued through the book.

Specifically on the subject of women, I think that the book did directly point out, both in the first 2/3rds and especially in the later 1/3rd of the book that the society and characters were VERY patriarchal, the story was focused on Kuni and Mata, and these sorts of stories often disregard women. Again, partly because I’d been prepared by Twitter, I found myself saying “OK, this ugly aspect of Epic Fantasy is being called out again and again, now what are you going to do”?

And that’s where my disappointment came in: the parts where women were finally included. Gin aside, the notion that women are better kite fighters and balloon riders because they are lighter than men felt simplistic, as did their role as auxiliary field medics. (My memory is that that’s mostly where they showed up in Kuni Garu’s army. Part of me wonders whether the women who accompanied many armies were already doing that generally unheralded job). It seemed that many of the women (certainly both queens) had moments of imposter syndrome – asking what they were doing there & whether their husband really loved them. While these emotions made sense in the context of the story, I don’t remember any men feeling similarly, despite the many men who are in fact in positions that they have no business being in according to the customs of their society.

I agree that there are places where the subversion/demolition of the patriarchal society & patriarchal tendencies in fantasy were brilliant – Gin’s victory in Rima being the in-your-face version, and the women singing near the end were two examples that really worked for me.

This is getting long – I definitely had a lot of (mostly positive!) thoughts about the book. I think it helped to go in with some expectation that the book was aware of & in dialog with many of the tendencies of Epic fantasy, and that some (particularly the role of women) took a while to play out. I still found myself disappointed in some of the ways that Grace of Kings brought women to the fore later in the book, but not enough to dampen my enjoyment of the text, just wishing for even more greatness. I’m also very curious about how the two women of the court will play out in book 2.

There’s a really interesting question here of how writers contend with wanting to have a dialogue with, subvert, or re-frame some of the usual tropes of epic fantasy.

A writer can simply write within the expected framework.

They can write through the usual frame and perhaps only introduce a single changed aspect (a kickass woman lead but not much else changed).

They can introduce the subversive element straight out, from the first page.

There is a bit of a risk using the technique Liu uses here, playing that longer game. He could have made other choices culturally, for example by not using historical patriarchal patterns for his society, but I really feel like this novel is in dialogue with a long tradition and acknowledges that. What makes it risky is that he thereby has to take his time unfolding what he is doing.

Here’s the thing, though: He is ALSO introducing your typical Western reader to a narrative structure they may not be familiar with, and that may take them some time to adjust to, as well as introducing a huge cultural milieu that the reader has to learn. So he’s juggling a lot of balls with the opening.

I’ve spent the past 10+ years reading/watching various Chinese classical texts & adaptations, so when I heard the book is a retelling/incorporates Three Kingdoms, I was pretty much set up to expect a cast of thousands. A thousand men, that is. I mean, the original text is so male-heavy it makes Tolkien’s three or four women look like positive parity. Sure, there are a few women in the original stories, but they’re pretty far and few between, so I was delighted when Jia showed up and held her own.

For that matter, I didn’t see Kuni’s speech as coming out of nowhere. The narrative emphasizes repeatedly that he often feels out of his depth, a little less competent than he wishes he could be, and someone who stands out purely because he’s had to overcome everyone’s assumption that he’s a nobody. He does get above himself at one point (and gets his head dunked in ice water, deservedly so) but for the most part, he does struggle with his own case of impostor syndrome. It’s even lampshaded in dialogue, that he’s the rare man who isn’t consumed by self-confidence. The only other doubtful male characters I can think of are all ones who inherited their positions as ignorant adults or near-adults (like a few of the kings plucked from anonymity, who weren’t really sure being the figurehead was really all that).

So it seemed to me entirely feasible that given his background, Kuni would have the empathy to see that women are taking part. Besides, the speech was foreshadowed. The enemy’s taunts about wearing dresses/makeup sent Mata into a towering rage, after all. Kuni’s reaction struck me as part of trying to calm Mata down, and at the same time, waking up to hearing his own words: why is it such an offense to say someone is like a woman? All the pieces were there, and it just took them falling into place for Kuni to put them together.

Speaking of pieces, I think part of the reason I ripped through the book so fast was the growing sense of the narrative giving me clues. I picked up on about half of them, but it didn’t all come together until I finally twigged on the setup (two men both aiming for the newly-made Kingship), and Mata’s reactions to Kuni getting there first. Pretty sure I yelled out loud while reading, partly at the delight of seeing the historical parallels, and partly out of surprise that it took me so long to realize we were heading into a retelling of the Hongmen Banquest. (Ken’s response on twitter was merely a self-satisfied, “hee.”) I honestly cannot believe I totally missed the clues about Liu Bang, when they’re littered through the text. (That said, if Jia goes the road of Lü Zhi, then you can definitely get out your gender-role knives, Kate.)

As for the women’s roles in the last third, the narrative was very clear to delineate the issue — that Gin was a true rarity for having any fighting skills, so the question became: what other skills do women have, non-battlefield, that are still useful? Kuni’s not perfect; his assumption was very much the camp-follower and laundry-washer. But from there, the narrative doesn’t let the women fade into the background. It highlights (repeatedly) all the ways that women’s skills are useful/used in the war-making engine: painting, needlework, sewing, cooking. Plus, women-only airborne troops, hard to beat that.

There’s a deft hand with other/newer political parallels, a wonderfully mature and complex relationship between Kuni and Jia, and so many other things but if I really get started, we’ll be here all night.

Agreed. The ROT3K is definitely not the typical epic fantasy structure, and Liu has to bring that to an audience that is unfamiliar with the “changing delta v” of the narrative and character flow. I am not entirely certain he pulls that off, though. I’ll be better prepared in book 2

Once I adapted (at the beginning) I had no trouble with the form, the layers, the short finite stories embedded in the longer stories, and strong omniscient narrator. It worked really well for me. Obviously ymmv but I enjoyed the pleasures of a well done omniscient voice (because so much current fic is so strongly third limited or first, thus so tight in its focus).

Nothing wrong with third limited and first — it’s what I write in myself — but besides the actual skill with which Liu deploys omniscient it was also just a nice change of pace.

It’s funny because I adored the structural elements and found myself slipping comfortably into the interludes of character history quite quickly.

There were really only two places where the book fell down for me. First, the strong theme of hardheaded practicality over received wisdom and accepting the signs of the gods seemed to be undercut partly by the “cool” elements that were not necessarily practical (alchemy that makes the chunnel possible, and then the development of steam engine powered submarines. Both are awesome, both also felt like they slipped into suspension of disbelief by virtue of being awesome), and also the active intervention of the gods (I’m really waiting for some of the male gods to weigh in on their opinions of women in positions of greater importance). Turning away someone who might be able to understand the motives of the gods is pretty silly if he indeed can pull it off.

Second, while I really liked the critiques of how women are often portrayed in Epic Fantasy, I didn’t like the solutions much (as mentioned above). But I do agree that it’s clear Ken is playing the long game.

There’s so much I loved about this book, in particular the narrative structure and the cinematic portrayal of battles, but those two elements were the bits that fell a bit flat for me.

A. Fishtrap,

Thanks for joining in! This is such a great novel!

Yes, I agree that Kuni’s empathy for women (and women’s position) is set up, and that the story does a good job building within the sequence of the battle to the point where he would react to the taunts as he does. I was speaking purely from a craft viewpoint: That is, I did not at that point recall having seen any women in the minor background roles that would suggest they were there–they only “become visible” to the reader afterward. So, for example, if the text had said (as an aside) a dozen women walked passed hauling water then it might not have seemed quite as sudden? Does that make sense? There are really very few women even in the background up to that point. So for me it wasn’t the portrayal of the men, or the men’s actions — that’s all fabulous.

I liked the variety of roles and skills shown in the last third, too! Another character I was very glad Ken included is (I’m blanking on her name and my iPad is not within reach) the woman who comes to avenge herself on Mata and instead becomes his lover. She really worked for me because to me she represented a very sympathetic and deft portrayal of a woman, with limited social agency, who nevertheless takes agency in the plot even within that limited sphere.

I have feelings about the idea I’ve seen expressed here and there that a work isn’t really feminist unless all genders are equal or it gender flips (I love both these kinds of stories too!), or that works that show women “beating the patriarchal system” are old fashioned and not really feminist . . . . if that’s true, what are we to make of women’s lives? Are no lives feminist unless they fit a certain template that makes them “more like men?” I think it honors and gives respect to the lives of women historically when we see this woman, with the choices she has, acting on them and being treated in a respectful way. If you see what I mean.

So — yes — the range worked really well for me.

I should have said in the post how much I like how Ken deals with Kuni, Jia, and (sorry no iPad and I read this book months ago) his second wife. Both women are interesting, strong, intelligent people.

I keep thinking there must’ve been women in the background, mentioned here and there, but then again — I guess we get so used to women being invisible in fiction that we learn to fill in the blanks. I mean, women are half the human race, so they must be around… somewhere, right? I’d like to think that was an intentional move on his part — to only bring women into the story once it had been so explicitly noted that they are, after all, half the human race.

You’re thinking of Mira, the woman whose brother was one of Mata’s soldiers. I particularly liked the parallels there with Kikomi, who despite taunting us with strong/intelligent possibilities, got stuck in the classic “seductive killer” trope. (I really, really loathe that trope.) Kikomi verged on genre-savvy, in that she seemed to know there was only one way she could play out; her story felt like she did X and said Y because that was the plot’s demand. Mira definitely transcends/subverts that trope — not only in being platonic, but in choosing to put aside the knife. The two acted as bookends, although I wouldn’t have minded if Mira had also found a way to dunk Mata’s head in a bucket of ice water, because damn, he needed it even more than Kuni.

I was going to say, “gender aside” (but even a passing familiarity with the past century of Chinese history renders some startling commentary buried in the text, seems to me, just google “women hold up half the sky”), but the story’s evolving treatment of its women characters echoes its attitudes towards tradition. Over and over, the story pushes away from venerated/traditional and into the future/possible. Some of the biggest mechanical and technological advances (like the mechanical crubin) don’t seem to really make any leaps until both halves, male and female, are working in combined effort. Or the nearly-blatant mockery of the King who insists on applying an archaic code, even to warfare, and it’s a woman who defeats him quite handily. If that wasn’t a sideways knock at the hidebound views of neo-Confucianism, I’ll eat my hat.

The entire story is full of easter eggs. I’m just really glad that a many of those easter eggs were also strong and complex female characters, too.

Yay, a discussion!

First off: fabulous article, Kate! I agree with your points and have a random assortment thoughts of my own to add-

– I too grimaced at the dancing girls in the procession, but then was rapidly distracted by FLYING ASSASSIN OMG. Hah. The overall tone of the first few chapters felt more to me like I was watching a really awesome political anime (like Juuni Kokki, one of my favorites) and so I was hooked, couldn’t stop reading, and then…

– Somewhere around 1/3 of the book, I almost put it down. I was getting impatient. Where were the awesome ladies? Why was Jia so singular? Dammit, how could the author do this to me? And honestly, if I had not had enough trust in Liu, I would have stopped. (Partly because at that time, it was around midnight.) But because I know that Liu is a thoughtful author and surely, surely could not have been this thoughtless, I kept going.

– I was well-rewarded! When I saw Gin I almost wept. It took the book long enough! But it was worth it.

– I am nervous about the next volume, because of the impending power struggle between Jia and Risana (and omg, Jia is so amazing and I feel she has been shafted — not by the author, but by, well, Life, because I seriously cannot fault how the author treated her story — yes political wives get soooo shafted ugh) and I’m hoping that Liu will rise to the challenge with something that subverts the women vs women narrative while still saying something meaningful and compelling about the nature of power and survival. This is a really difficult thing to pull off! But I’m confident that Liu can do it. (At the same time I’m nervous, because I don’t know what will happen and I want the next book now now now. Augh.)

– This book was literally unputdown-able. I cracked it open before bed, thinking I’d read the first chapter and go to sleep, and ended up staying up all night to finish it. So masterfully told.

– Kikomi broke my heart. Her arc… well, I don’t want to say the way it ended was inevitable; I still wish, so much, that a different end for her could have happened, because I must admit to a frisson of rage at her end. I applaud her as an amazing person who got shafted by Life (the way Jizu was) and I understand why her story ended as it did. But dammit. Kikomiiiiii.

– How cool is it that there is a queer character among Kuni’s inner circle and that he’s the fierce and terrifying warrior? You go, Mun Cakri!

A. Fishtrap: Thanks for all these insightful discussions of how tGoK fits into the tradition (which I only know in a vague “read a few things and know a bit of history” manner). It’s so illuminating.

Yes, Mira turned out to be one of the my favorite characters and I could not even say why. I think maybe it was just the tidying up and her fearlessness. There are forms of courage that so much narrative ignores, and hers is a kind that I loved seeing highlighted.

Very much agreed about how the text is both giving a nod to and pushing against tradition, too.

Mia — yes, Risana. I loved how both Jia and Risana are strong, intelligent, knowledgeable, skilled women. And I completely agree with your discussion of — what will happen in book two!

My reactions very much were similar to yours as I read.

Thanks for the excellent review Ms. Elliot! I’m literally fresh off this novel (finished it just a few hours ago), so things are kind of jumbled up in my head, and this review provided a lot of perspective.

Re: the women – I was initially worried when I realized that they were few and far between at first. I was already seeing the similarity to Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin/Outlaws of the Marsh, where women are so few in comparison to the men they might as well not exist at all, and I was worried that this was going to be a repeat of that. But when they started showing up, I was pretty happy with the way they were being written, for the most part.

I was especially happy when it became obvious that Liu wasn’t going to characterize them as these paragons of specific virtues or flaws: Jia, in particular, could have become some kind of paragon of long-suffering, wifely perfection (a la Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey), but she isn’t. She makes mistakes; she gets jealous; she’s not above feeling petty and doing little things that satisfy that pettiness. Her relationship with Kuni is also very interesting because it’s not a straightfoward romantic story (although it starts out that way, which also had me worried; I’m always suspicious of anything that smells of “love at first sight”). She’s HUMAN, and I like human. Gin’s the same, and so are Mira and Kikomi (Kikomi has shades of an old Chinese story I think I may have read before; can’t remember what it was specifically, though). Risana, though, makes me want to squint and look at her sideways. I’m a little worried because she seems to lack a certain layer of complexity I’ve seen in the other characters I’ve mentioned, so I hope that in the next book, Liu does right by her.

And speaking of women: I absolutely adore Soto. I’m so very happy that Liu wrote her in; there need to be more middle-aged-to-elderly women as prominent characters in genre fiction. I know that, thus far, people are projecting conflict between Jia and Risana, but I don’t think we can forget that it’s Soto who’s standing behind Jia and nurturing her to become a political wife, and I really want to see how she gets involved in other events further down the line.

And speaking of the Odyssey, it might be because I started on this novel after doing a quick skim of Homer’s duology, but I kept seeing shades of both the Iliad and the Odyssey in the novel. Sometimes it was in the language: things like “misty, salt-kissed Boama”, or “ring-wooded Rima”, or “fruitful Faca” – they all have echoes of similar phrases in both the Iliad and the Odyssey. Other times it was the characters: Mata’s Achilles vs. Kuni’s Odysseus, for example. And then you mentioned the gods as a Greek chorus, plus the fact that they influenced the mortals the same way the gods did in Homer’s work. I know that if this novel might be said to have any antedecents in the classics it’s Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin/Outlaws of the Marsh, but I can’t help but see Homer in it, too. Of course, I could be over-reading it too, so…yeah.

I wasn’t really interested in this novel (perhaps just haven’t not read enough about it, or perhaps having read too much fanfare about it…”Ken Liu writes a novel OMG” etc., when I wasn’t familiar with his work).

Well. This post and the comments make me think, “Wow, I gotta read this!” I was expecting to just be interested in your reading/blurbing process — I didn’t realize I’d get caught up in the details. ;-) Thanks, all. Interesting discussion and I’m very intrigued.

I thought Soto was an interesting character. To a degree she was there as a cipher or to provide some exposition but then it was also much more than that. The role she played in helping Jia and Kuni reject traditional interpretations of their roles and in helping Jia understand her power as a “political wife” was well thought out. I also though it was deftly done when she faced down Mata. She was one of the most interesting characters I thought.

I also am intrigued by Soto and agree with Kam and Stewart about her interesting she is. So far I’m reserving judgment about her long-term roles as I feel she is going to be deployed more fully in book two and I’m looking forward to how she becomes involved in the court politics — and there will assuredly be court politics.

Kam, that’s a great analysis of the influence of Homer, and in fact I am pretty sure Liu mentions in interviews that Homer is an influence.

Just re-reading through the comments (and thanks to everyone!)

Jonah wrote:

” It seemed that many of the women (certainly both queens) had moments of imposter syndrome – asking what they were doing there & whether their husband really loved them. While these emotions made sense in the context of the story, I don’t remember any men feeling similarly, despite the many men who are in fact in positions that they have no business being in according to the customs of their society. ”

Kuni does question himself to some extent but I think you are correct that on the whole the women question themselves more while the men do so less, and that in itself may be an unexamined choice by writers.

I say writers because in my own writing I *often* in second and third drafts have to stop and look at how I am writing the women and make them more assertive, more demanding, more in charge, more proactive — and I’m often writing within cultures that are more gender egalitarian yet meanwhile dragging my own complex upbringing and issues in with me as I write.

This is really a central issue for me when I look at epic fantasy. For example a book that places a few women in traditional male roles with traditional male status while leaving the unexamined bias against women’s lives mostly intact does not feel particularly feminist to me right now. It is such a complex issue, and I think all these comments are very apropos.

[…] A lot has been said about the lack of women in The Grace of Kings. A quick glance at Goodreads, shows me that most reviewers share my frustration when mentioning how for the first two thirds, apart from Jia, the governess Soto and the brief appearance of Kikomi, there are very few female characters appearing at all. When they are briefly mentioned, they are prostitutes, dancers, mothers, wives, who all play those very specific roles when they appear (Kate Elliott wrote an interesting take on this and the comments on that thread are well worth a read). […]

[Editor’s Note: this is not a critical essay in the classical sense. It is an entry from a reading diary which indicates bother by the presentation of women in the novel.]