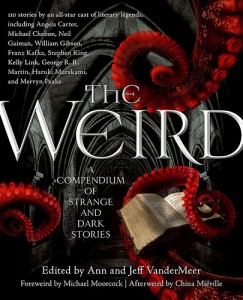

This week saw the publication in the U.S. of a massive (Amazon shipping weight for the hardcover: 3.1 pounds!) new anthology of fantastic literature: Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. Initially published in the U.K. by Corvus last fall, this book contains 110 stories of fabulous, bizarre, sometimes esoteric weirdness. I read the whole thing at the end of last year, and it has produced a lot of fodder for contemplation. I found it difficult to write a brief, crisp review of it (although a review is in progress), but what really made this book significant to me is that I have been able to turn the stories over and over in my mind and find insights into reading, writing, story, genre, and some tenebrous insights into how I look at life and reality. Even better, some of the stories require you to struggle, to navigate your way through discomfort and perplexity, to really experience their value. I’ve written about it several times, and it has inspired a chapter in the book I’m currently working on. What’s great about The Weird is that you can find all kinds of odd, perplexing, sometimes horrible things in it, and once you take them in they start to worm themselves into your thoughts and ideas.

This week saw the publication in the U.S. of a massive (Amazon shipping weight for the hardcover: 3.1 pounds!) new anthology of fantastic literature: Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. Initially published in the U.K. by Corvus last fall, this book contains 110 stories of fabulous, bizarre, sometimes esoteric weirdness. I read the whole thing at the end of last year, and it has produced a lot of fodder for contemplation. I found it difficult to write a brief, crisp review of it (although a review is in progress), but what really made this book significant to me is that I have been able to turn the stories over and over in my mind and find insights into reading, writing, story, genre, and some tenebrous insights into how I look at life and reality. Even better, some of the stories require you to struggle, to navigate your way through discomfort and perplexity, to really experience their value. I’ve written about it several times, and it has inspired a chapter in the book I’m currently working on. What’s great about The Weird is that you can find all kinds of odd, perplexing, sometimes horrible things in it, and once you take them in they start to worm themselves into your thoughts and ideas.

Well, they do for me at least.

And this is what I want to discuss in this blog post: the idea not just of weird fiction, but of how genre expectations — as reading frameworks — condition our engagement with fantastic literature. We all have our preferred categorizations for the stories we read: some people like SF, others speculative fiction or fantastic fiction. Some readers want to organize stories more precisely, right down to very specific sub-genres like paranormal romance or steampunk. Some people like micro-designations, while others like a big playing field. Myself, I was a rabid, obsessive parser of subgenres as a younger reader, but I found after some years that I was reading the same sort of stuff constantly, and I was getting, well, bored. I came to realize that my problem was with how I looked at genre, how I used genre and how my expectations and assumptions influenced my reading of a story. I have evolved into a big-tent sort of reader of fantastic fiction, to the point where I prefer to use the term fantastika, precisely because it opens doors into stories rather than closing them. It also incites discussions about genre and how we look at the stories we enjoy reading, and I like that.

Within that broad category I do see some distinctions, but I see them, and genres in general, as interpretive schema, rather than labels that fix a story’s identity. Genres do not just categorize; they establish (or occasionally question) a lens for our perception of a text. In fact, using genre as a term of fixity usually creates a presumption about a story that limits what a reader might find in it. The very terms we use all contain assumptions about what we are looking for in a story and what it is trying to do. For example, the idea of speculative fiction is a popular designation for fantastic literature, but one that I find simultaneously too vague and too leading. All fiction is a speculative endeavor, for writer and reader. Most definitions of this term point more specifically to the idea of conjecture and extrapolation, of a story that creates a world different than ours (contemporarily or historically) to explore. But within such definitions is a conceit that the story has to lead us to a particular speculation, a “conjectural consideration of a matter” in a positivist direction.

Contrast this with the idea of weird fiction as a possible genre designation. Weird fiction is harder to define than speculative fiction: China Miéville states that weird fiction is “fantasy, SF, horror and all the stuff that won’t fit neatly into slots.” In their introduction to The Weird, the VanderMeers assert that “The Weird is as much a sensation as it is a mode of writing.” What sets weird fiction off from other stories is that it is not easy to define, but that it creates an atmosphere and a sensibility in the reader’s mind that dislocates and unnerves the reader. It is not the opposite of speculative fiction, but is a different approach in the writing and reading of one. The root of the word weird is “uncanny, bizarre, and concerned with fate.” Speculative fiction is usually not about fate, but about a different direction; weird fiction is deeply concerned with fate, with notions of destiny and the unknowable. Each idea has presumptions about where a story is going and what we are looking for when we read it.

This leads me to ask: if you go looking for “speculative fiction” and find “the weird,” what is it that is disappointing? If you want to be weirded out by a story but aren’t, what is it that lingers and bugs you about it? Does it come down to predictability versus mystery? Each idea is a predication, but looks for something different than the other (even though “weird fiction” is sometimes sublimated beneath the rubric of speculative fiction). There are assumptions attached to the ideas of speculative fiction and weird fiction; sometimes we suspend them, other times they become the basis for rejecting a story. The conceit that I find embedded in the idea of speculative fiction is its premise that we must find something progressive in a story, a confabulated certainty that we can unearth and construct in our reading mind. But that is only one way to look at a story. What I find compelling about looking at stories weirdly, whether they fulfill that expectation or not, is the potential for being reflexive. The world is a strange place, and we as humans spend a lot of time trying to make sense of it and then striving even harder to make it recognizable, graspable, real. Speculative fiction as a genre predisposes that we must find something; the weird isn’t sure what we will find, but what we uncover will seem simultaneously inevitable and ineffable.

I recently wrote that “certitude hides more than it exposes. . .weirdness, in the literary and literal sense, is all around, and powerful art can emerge from it.” What I found in The Weird was a series of lessons in what weirdness can inspire in the art of fiction. I worry sometimes that our genre designations constrain, rather than liberate, our imaginations and our capacity for interpretation. In the rush to define stories we can lose sight of the fact that we create the meanings we find in them. Reading is not just an act of cognition, but an act of evocation. If we could open our genre expectations up, think more critically about them, and apply them more playfully to the stories we read, I wonder what new and wondrous things we might find in them.

[…] A Dribble of Ink (John H. Stevens) on Genre Predispositions and The Weird. […]