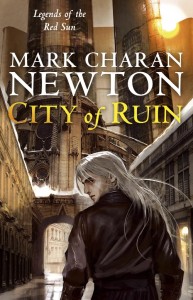

City of Ruin

Author – Mark Charan Newton

Hardcover

Pages: 400

Publisher: Tor (UK)

Release Date: June 4, 2010

ISBN-10: 0230712592

ISBN-13: 978-0230712591

The New Weird. It’s that strange little literary movement that, according to Mark Charan Newton, is dead. And yet, he’s flying that mantle high, telling anyone who’ll listen that City of Ruin, the second volume of his Legends of the Red Sun series, has been let of its leash by virtue of a four book publishing deal; it’s going to be weirder, more true to Newton’s original vision of the sun-deprived Boreal Archipelago. Nights of Villjamur, Newton’s first novel (REVIEW), dabbled in the New Weird, but City of Ruin is meant as a love letter to two ailing genres (it’s also very much in the vein of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth novels and Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun), and promises to be the unrestrained novel Newton wanted to write in the first place (it’s not easy to sell giant spiders, floating spaceship islands and geriatric cultists to publishers, I guess.)

The New Weird movement is one I’ve only watched with vague disinterest from the sidelines. It just wasn’t for me. I’m too traditional, too happy to read novels I recognize. Why would I need weird for weirdness sake? At least, that’s what I thought. I was worried that the New Weird would take too much to wrap my head around, would be more trouble than it was worth. But, if City of Ruin is such an example of the genre then, well… the New Weird just isn’t as weird as the reputation that precedes it. Rather, it’s Fantasy with an open mind, Fantasy that steps away from Elves and Dragons and replaces them with smoking, male banshees and corpse golems. My early perceptions of New Weird were that I’d constantly be forced to reevaluate how I approached the place and setting of the novel, to push aside preconceptions and learn again how to listen to a story; but, really, in the end, a hulking, angry coin golem is just a fresh coat of paint on a troll, and a city-stomping cephalopod is just a dragon in disguise.

But I digress, this isn’t an essay about my ill-conceived misconceptions, but a review of a novel that draws influences from many genres beyond New Weird. There are touches of Epic Fantasy (cross country travelogues, complete with aloof, drunken swordsmen and tangential encounters with ravenous tribes) and Urban Fantasy (with a few battle scenes that would make the film version of Children of Men jealous), dusty old detective novels (with noirish undertones galore), but most interesting are the ties, intentional or not, to Cyberpunk and near-future Science Fiction. Among the new characters introduced is Malum, a gang leader and Vampyre, who reveals the seedy underbelly of Villiren. His story arc, full of gang politics, cigarettes, smuggling and whores, a constant reminder that this is a tale told not in the past, on some fantastical other world, but in a far future of our own. This isn’t your grandma’s Fantasy:

Under a sleet-filled sky, in a area of the city currently blocked off for renovation, Malum and the banHe had words.

The banHe smoked his roll-up nervously, as if paranoid, though there were always a couple of his thugs loitering nearby, their boots crunching on the vacant rubble-patch. This place used to be an educational establishment until the rents got too high, but now it was marked out for being turned into a larger apartment block. At the moment, it made a good place to meet: there were no places to hide a crossbow, not even enough cover behind which someone could crouch with a blade.

‘What is it, Malum?’ the banHe enquired, an almost musical quality to his voice.

‘Portreeve says there’s going to be a massive march of strikers heading through the northern districts – protests from stevedores on the docks, support from the smaller merchants, that sort of thing.’

‘What they angry about?’

‘Dangerous working conditions mainly.’

‘Why ain’t they taking it up with their employers? What’s Lutto got to do with it? It’s a free market, right?’

Malum smirked. ‘C’mon, you know better than that, Dannan. Private companies in this city means no one takes responsibility for things like deaths occurring at work – mainly from hypothermia at the moment. No one wants to work shit jobs for shit money in the ice, especially when they’re dying all round, but their employers say shut up or they’ll just ship in cheaper workers from off-island. Even talk of slaves coming in to work for next to nothing, though Lutto told me that he’s uncomfortable with that – might spoil his image back in Villjamur. Not even the Inquisition can get involved, in case it sends out a bad signal – that there isn’t much democracy here. Got to create the illusion of freedom just to placate the rest of the masses.’

This is balanced by the more traditional stories of Randur and Brynd Lathraea, both returning, rather dubiously, from Nights of Villjamur. Their’s are stories of quests and tactical, large scale warfare, racial tensions, sword fights and invading armies. This balance lends the novel more variety than its predecessor and shows Newton’s ability to tackle large scale stories from multiple angles. That said, the story meanders through the first 2/3rds of the book, dropping storylines and characters for long periods of time while focusing on others, and could have used some tightening and better pacing leading up to the, admittedly, page-turning climax.

The crutch of the novel is Villiren. A Fantasy version of Los Angeles, Villiren lives off the debauchery and sin of its inhabitants. Gangs rule the streets, and inanimate, lifeless sex golems fill the beds of all damned souls waiting for the sun to die. It’s reputed to be the wealthiest city in the archipelago, but lacks a real defined governmental system, instead letting the gangs and a corrupt Port Reeve (whatever that is) run the show. Newton’s proving himself to be adept at creating these Gormenghast-esque settings, infused with as much character and importance as any of the living characters, but forgets that, ultimately, the reader has to invest themselves in the city if they’re supposed to fear for its safety. Villiren is as fully realized as Villjamur, but I often felt it would be better if it were just invaded and destroyed, for there was little worth saving. To Newton’s credit, one of his characters struggles with this very concept, but when most of the story is told through the eyes of outsiders to the city, who struggle with its chaotic personality, it becomes hard to empathize with Villiren’s plight. As they title suggests, Villiren is a city on the edge of ruin, it’s fucked no matter what happens, so why bother to save it? Distressingly, it’s what’s most recognizable in Villiren that makes it so vile. Newton draws upon our world and gets too many of the little details alarmingly right.

Again, like Nights of Villjamur before it, City of Ruin has a detective story at its heart, but Newton lets the spider cat out of the bag on page one. Rather than explore and reveal the mystery through the eyes of Rumex Jeryd, the investigator, we’re introduced to the killers in the prologue of the novel. Sure, their motives are cloudy, and the reveal is genuinely pleasing and twisted, but much of the tension whodunnit fun is stolen from Jeryd’s story when the reader already knows so much more than he does. As he searches for the identity of the murderer, he seems more like an old, weary, bumbling fool rather than a seasoned pro.

The characters that return from Nights of Villjamur are all fleshed out further, but I constantly felt like they (aside from Brynd Lathraea, who has an honest, necessary reason for being in the city) were forced into Villiren’s story, as opposed to an natural piece of the puzzle. With Newton returning to Villjamur in the third volume of the series, I would have appreciated if he took a Steven Erikson-like approach, introducing a new cast of characters for us to learn and love, eventually merging their stories with those from the first novel. As it stands, the old faces were familiar, but got in the way of Malum, Lupus and Beami, (newcomers all, and sharing in the most interesting storyline of the novel.)

It entered the deep night, a spider reaching taller than a soldier. Street by street, the thing retched thick silk out of itself to cross the walls, using the fibrous substance to edge along improbable corners. Two, then four legs, to scale a wall – six, then eight, to get up on to the steps of a watchtower, and it finally located a fine view across the rooftops of Villiren. Fibrous-skin tissue trapped pockets of air and, as tidal roars emerged from the distance, the creature exhaled.

A couple walked by, handy-sized enough to slaughter perhaps, their shoes tap-tapping below – but No, not them, not now, it reflected – and it slipped down off the edge of a stone stairway to stand horizontally, at a point where observation took on a new perspective. Snow fell sideways, gentle flecks at first, then something more acute, adding to the brooding intensity of the streets.

Within this umbra, the spider loitered.

As people sifted through the avenues and alleyways, it sensed them by an alteration in the chemistry of the air, in minute vibrations, so no matter where they were they couldn’t hide. With precision, the spider edged across to a firm overhang constructed from more recent, reliable stone. Webbing drooled again, then the creature lowered itself steadily, suspended by silk alone, twisting like a dancer in the wind. Lanes spread before it, grid-like across a plain of mathematical precision. The frequency of citizens passing below had fallen over the last hour; now only a handful of people remained out to brave the extreme cold.

It could almost sense their fear.

One of them had to be chosen – not too young, not too old. The world collapsed into angles and probabilities as the creature made a controlled spiral to the ground.

Scuttling into the darkness, the spider went in search of fresh meat.

With the release of Nights of Villjamur, Newton’s prose was divisive for its loose, stream-of-conciousness style. People either loved it or hated it. Strikingly, especially to those expecting a Fantasy novel (as it’s generally marketed as), the prose is very contemporary, a seemingly intentional move on Newton’s part to, again, solidify the fact that this tale is being told on a future version of our world, far removed from contemporary times, but with echoes of our language and culture still intact. This anachronistic language fits in the Cyberpunk-esque Villiren much better than it did in the Medieval-esque Villjamur, especially when dealing with the locals; it’s like comparing the expectations when a Scottish farmer opens his mouth to a SoCal teenager. Newton is a better writer in City of Ruin, but it will likely do little to change the minds of those who were put off by the prose in Nights of Villjamur.

It’s clear, also, that Newton has things to say. Like his inspiration China Mieville, Newton fills his novel with political and social commentary, reflecting on the state of our world, our culture and our cities through the destruction of those in his novel. Beyond the parallels between Villiren and Los Angeles (with a bit of London thrown in, I expect), Newton explores racism, sexuality and prejudice, though never hits you over the head with his philosophies. If there’s one are where Newton improved immensely, it’s this. Unlike Nights of Villjamur, much of the commentary and philosophy evolves naturally from the plot, rather than being revealed by blatant internal monolgues by the characters.

Rather than being intimidating in its ‘weirdness’, City of Ruin is, instead, an fantastically inventive look at familiar tropes and archetypes, and full of visual marvel. As with Nights of Villjamur, City of Ruin further proves that Newton’s an author worth watching closely. Pulling from its myriad influences, City of Ruin takes the best of many genres and blends them together into a refreshing mosaic, never quite letting the reader get comfortable with their preconceptions, and constantly pushes at the boundaries of imagination. If City of Ruin is an example of the (New?) New Weird, then it might not be as brain-bending and weird as I’d feared, but it is bloody good.

Sounds like Newton’s take on fantasy is refreshing and accessible and well-written. I can only hope his work is on par with Mieville and VanderMeer and the way they tackle familiar tropes from oblique angles and dress them in unfamiliar skins. Despite their approach, I don’t consider their works to bend the foundations of fantasy writing to an unrecognizable form. The thing that really separates New Weird authors from most fantasy writers is a quality of writing that we don’t normally find in standard fantasy.

This is exactly what I feared from New Weird, but I’m quickly realizing that I was fooled by my own preconceptions. Having not read (much) Mieville or any Vandermeer, I can’t comment on how Newton stands up to them, but CoR and NoV are certainly impressive (if flawed) novels. Newton’s also got a fine sense of voice, which is always good for Fantasy.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Mark Charan Newton. Mark Charan Newton said: RT @adribbleofink: New Blog Post – My review of CITY OF RUIN by Mark Charan Newton (@MarkCN), an atmospheric mosaic of many genres: http://bit.ly/bvJyU2 […]

The New Weird appears to be extemely readable. China Mieville uses some unusual diction and relatively rare words, but his actual prose is reasonably straightforward and flows well (aside from KRAKEN, where it gets tangled up a bit in the first half before straightening out). Steph Swainston, another standard-bearer for the genre, is also pretty easy to read, whilst retaining that weird element.

Dense, difficult-to-read prose was, I figured, a hallmark of the sub-genre. I was surprised when I read The City & The City by Mieville, because it was a relatively easy read (at least the prose, the conceit of the story was hard to wrap my head around at first), but just assumed it was atypical to Mieville. My interest in reading more Mieville, Vandermeer and Swainston has increased fairly significantly over the past few days.

I cannot recommend Finch highly enough. It’s one of the best I’ve read in the last year. There story has amazing resonance. I find myself thinking about it months later.

The phrase “banHe” makes me shudder, to be honest. It isn’t a fraction as clever as it thinks it is. What a turnoff on what is otherwise an interesting sounding novel!

On a better note: @Adam, I’m happy to see my reaction to Kraken is shared by someone else. I recently read an interview with Mieville who said that he tried a more conversational, loose tone with this book, and that if it meandered a bit it was fully intentional. It might have been a blast to write, but sure was a slog to read. I was thankful that he cranked it into high gear finally towards the end.

@Aidan + Jonathan: Finch was fantastic, agreed. However, since it is the third in a loose trilogy (‘City of Saints and Madmen’ and ‘Shriek: An Afterword’ being the first two) I would definitely recommend leaving it til last. Much like reading Mieville’s Bas Lag books out of order, I wince to think of the person who picks up Finch without any prior introduction to Ambergris.

Also, wasn’t it curious that both Mieville and VanderMeer each released a noir/detective thriller this past year? Neither was acutely comfortable in that genre, but it was exciting to see them toe their authorial lines!

[…] also posted his review of Mark Newton’s City of Ruin – hope you’ve read it and enjoyed it as much as we did! Mark has got some awesome stuff […]

I was worried that reading Finch would leave me in the dark (I usually read series in order, but that cover and the promise of a strange ride pushed me to read Finch). If anything, I thought VanderMeer’s allusions to the first two books provided the feeling of history, of depth that I enjoy. The Duncan Shriek stuff piqued my curiosity and now I am compelled to read Shriek: An Afterward and City of Saints and Madmen.

[…] my recent review of Mark Charan Newton’s City of Ruin, I hummed and hawed over my preconceptions of the New Weird, a genre that you had a hand in […]

[…] to read the third volume, The Book of Transformations, especially since I enjoyed City of Ruin (REVIEW) so […]