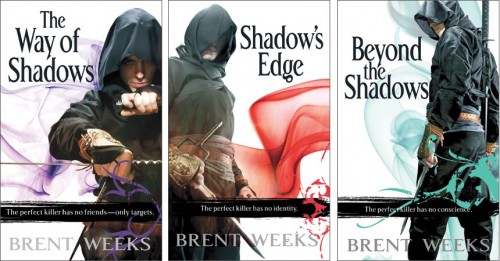

Brent Weeks needs little introduction. Since releasing The Night Angel Trilogy just two years ago, Weeks has become one of the most popular new writers of Epic Fantasy. His tale of wetboys and guild rats put him on the map, but Weeks is back with The Black Prism, the first volume in The Lightbringer Series, and he’s ready to prove that the success of The Night Angel Trilogy was no fluke.

Brent Weeks needs little introduction. Since releasing The Night Angel Trilogy just two years ago, Weeks has become one of the most popular new writers of Epic Fantasy. His tale of wetboys and guild rats put him on the map, but Weeks is back with The Black Prism, the first volume in The Lightbringer Series, and he’s ready to prove that the success of The Night Angel Trilogy was no fluke.

Brent and I sat down (err… traded emails) and chatted about everything from Matchlock-Fantasy to the difference between bloggers and casual readers, magic systems to Mary Robinette Kowal, plot twists to building Fantasy worlds, and, of course, his latest novel.

Brent’s a cool dude, and this was one of the easiest and most enjoyable interview’s I’ve conducted. This guy gets what it takes to be a writer in the 21st century. But, let’s let Brent do the talking, yeah?

The Interview

Welcome, Brent! Thanks for taking the time to drop by A Dribble of Ink.

Delighted to be here, Aidan. Thanks for inviting me to your, um, office.

The Black Prism has several point-of-view characters, but mainly jumps between Gavin Guile and Kip – one a young boy caught in a political hurricane, the other is the most powerful man in the world, and a veteran of countless battles, political, religious and physical. Was it difficult for you to jump between these two very different characters? What does the contrast between them add to The Black Prism?

No, it wasn’t difficult. There are plenty of things about writing that are hard, but for me getting into different characters’ shoes isn’t one of them. It’s actually one of the most fun parts of what I do–and there are a bunch of reasons, structurally and artistically, why I chose characters who were so very different from each other. I try to give myself new challenges with every book I write–harder challenges, so that I keep developing my skills. Something that’s hard in fiction is to take a character at the top of the world and make you care about him. That’s Gavin Guile. He’s not only powerful, he’s rich, he’s intelligent, he’s handsome, he’s universally respected, he gets whatever he wants without it seeming like he works for it–pretty much everything that would make you want to hate a guy. At the very least, a character in that position is hard to identify with, even if you admire him.

Compare that with the typical fantasy hero: a guy who comes from nothing and grows in power until he can face the Big Bad credibly. That typical underdog story–which is Spiderman, Harry Potter, Harry Dresden, and ten thousand others not done so well–has some big advantages with an audience. It’s easy to root for an underdog and to identify with him, because we’ve all been there. There’s a triumph we feel as he or she triumphs–we’ve been there with them through the thin, and they are us, so when they finally get the payoff, we’re getting it too. It’s a powerful tool in any writer’s arsenal–and I decided to forgo it this time.

So if I’ve got a main character who’s intriguing at first, but is going to take you a while to really fall in love with, I’ve put a hurdle in readers’ way. Being the nice storyteller I am, I thought I’d help them over the hurdle. That help is Kip–who is a ways away from being a stereotypical boy-out-to-save-the-world himself. He’s a fat mixed-race kid with a smart mouth and a single mom; he’s got a crush on a girl who doesn’t like him back, and he doesn’t like himself all that much. To balance that, he’s funny and he underestimates himself constantly: he’s braver, smarter, and better than he thinks he is.

One is the vastly privileged insider, and the other is naïve, young outsider. Their differences bring different perspective to the world itself and the problems their world faces.

Kip really is a great foil to the average kid-with-secret-lineage often found in Fantasy novels. There’s a great quote near the beginning of The Black Prism:

Kip really is a great foil to the average kid-with-secret-lineage often found in Fantasy novels. There’s a great quote near the beginning of The Black Prism:

“Kip. Well, Kip, have you ever wondered you were stuck in such a small life? Have you ever gotten the feeling, Kip, that you’re special?”

Kip said nothing. Yes, and yes.

“Do you know why you feel destined for something greater?”

“Why?” Kip asked, quiet, hopeful.

“Because you’re an arrogant little shit.” The color wight laughed.

I read that passage a couple of times and really had to grin to myself. It was refreshing to see an author tackle the genre tropes with an almost literal flip-of-the-bird. I knew I was getting into a novel about a boy with a hidden, magical past, but I wasn’t expecting those preconceptions to get toyed with by the text. The Black Prism is still very recognizably Epic Fantasy, but were you determined from the outset to throw some curveballs at your reader?

I had a professor who talked about genre being a contract with the audience. I think that’s a pretty fair definition. So, while I love epic fantasy–love it–I wanted to give fair warning early that I write worlds where the bad guys can win, where the boy-destined-for-greatness may not make it to book three. There may be prophecies, but you don’t know if the prophet is inspired and what he says Must Come True, or if he’s just the neighborhood crazy man. It’s a world with a lot of uncertainty.

So yes and no. I’m giving readers fair warning that curveballs are possible, but–uh, not to stretch the metaphor too far–but not saying that I’m going to try to hit batters with my pitches. I like to write surprises, but I want those surprises to be the kind where a reader goes back and re-reads the paragraph to see if That Really Happened. I don’t want the kind where a reader throws the book across the room.

To go back to the contract idea–I can break the contract if I break it in pleasing way.

Speaking of surprises, much of the dramatic tension in The Black Prism relies on a huge plot twist (that I’d *love* to talk about in detail with you, but won’t, in fear of book-ruining spoilers). While reading The Black Prism, I found myself jumping back and forth between being enthralled by the twist… and finding it a bit of a stretch, especially the twist’s relationship to some of the important secondary characters.

Where’d you find the courage to centre your novel around such a huge plot twist that, more or less, requires readers to suspend belief for a moment and buy into the concept before it’s fully explained?

When you’re dealing with any significant plot twist, there’s all these tensions that you have to hold in balance like the anchor lines of a spiderweb–if any of the major ones break, you’re going to lose half the structure. You keep in balance what the reader knows, what the main characters know, and what all the supporting characters know. In addition, if you want to have more than one twist, you can’t rush to throw in a bunch of extra lines to support the structure.

I enjoy writing plot twists and I do my best not to cheat as an author. Is it a stretch? Yes! Part of the reason I put that twist where I did–early–was so readers could go through those questions. If you put the same twist at the end of the book, it would be TA DA! Big reveal. End of book. The surprise certainly is climactic, and would propel you into the next book. But I didn’t want to do that. I wanted readers not just to say, “Wait, how did he do that?” But also to get to ask, “How does he continue to do this? And was he really as successful as he thought he was? Because it seems like kind of a stretch.”

Whether all readers buy it is a different matter. Any time you write something that goes out on a limb, you’re going to have people who don’t buy it, either because you don’t do it well, or just based on their own experiences. Have you ever known someone for years and spent lots of time with them, but they still remained a cipher to you? Or on the other hand, are you the kind of person who can’t even keep the birthday present you bought your dad a secret for three weeks? Those two readers are going to require different levels of textual evidence for a character who keeps a huge secret. To go far enough for one reader may well be beating it to death for another.

That you–who must read in a critical mode–only found it a bit of a stretch at times tells me that it will probably work for a lot of readers.

One of the most obvious and defining aspects of The Black Prism is its magic system, something you clearly spent a lot of time developing. Were you ever afraid that the magic system would become too large a beast and get in the way of the characters and story?

Not the magic system itself, but my explanation of it. My characters live in a world where the magic is profoundly influential. That’s no big deal. Look at electricity in our world. How much do most of us know about how a TV really works? If an apocalypse came, could most of us rebuild a TV? For how we experience the world, TV just is. There is a lot of mental work that goes into building a profoundly influential magic system, but–and maybe this is the heart of your question–how much of it should I show at one time? Even when dealing with writing a huge long fantasy book, every page is a finite space–and every reader’s attention span is, too. The more time I spend describing the magic, the less I have to describe the characters and the world and politics, and the less space I have for meaningful action or dialogue.

By making the magic integral with the social structure and the politics, I was able to have some of the magic explication serve multiple purposes: a person who can use two colors has better social status and some satrapies pay that person better than others will and try to lure them away. That tells you about magic, about the rarity of drafters, and about the jockeying that happens between the satrapies.

All that said, I also look at worldbuilding in a big fantasy as something that happens over three books. So I let some things go for later books that would have been fun to talk about–for the sake of space and pace.

These days a lot of Fantasy seems to live or die based on its magic system. Authors like Brandon Sanderson and Blake Charlton seem like good examples of this, where an intricate magic system is as much a part of the novel as its characters, plot or world. What’s the appeal of developing such an in-depth magic system, instead of using something more esoteric (or, conversely, recognizable) and focus more on the traditional aspects of a novel?

These days a lot of Fantasy seems to live or die based on its magic system. Authors like Brandon Sanderson and Blake Charlton seem like good examples of this, where an intricate magic system is as much a part of the novel as its characters, plot or world. What’s the appeal of developing such an in-depth magic system, instead of using something more esoteric (or, conversely, recognizable) and focus more on the traditional aspects of a novel?

I won’t lie, part of it was to show I could. When you have a magic system where magic is rare, and the explanations are given slowly and over the course of three books, it’s not going to be part of the story that people gravitate to or mention first.

I’ve been thinking a bit recently about the problems of your job Aidan. Look, you’re a reviewer. That means you necessarily read more and differently from most SFF fans. A lot of fans will discover a writer and then devour everything that person has ever written. You bloggers have it tougher. You need to read something, form an opinion, articulate it, and move on. You have pressures to cover everything, and to not focus on one author for multiple books in a row–lest you be accused of being a shill for them. (Didn’t some blogger run into that recently?) Add to that the pressure of Oh, you should read some sf classics too–and don’t neglect those under-appreciated writers! Oh, and read outside the genre or your blog will stagnate! … And your job gets pretty tough.

It also, unfortunately, means that you read less and less like an average fan. (If there is such a thing.) There’s clearly both great things about having an astoundingly broad knowledge of the field, but when you come across a writer like me, it means that if I do something brilliant in book three of Night Angel that I’ve been setting up for two books, it’ll pay off for a ton of fans, but most reviewers will never see it.

I like to think I do some brilliant stuff with magic in Night Angel, but it unfolds slowly, and characters lie about it so it appears to be contradictory with what you’ve been told before, and people within the book misunderstand it because they have a pre-Scientific Revolution understanding of the world.

So basically, I dumbed this book down so bloggers would get it.

Just kidding.

Really, I was writing a new book, and I wanted to come up with magic that was different and fun. I’d written a book with low magic–where magic is rare, and I wanted to try the other extreme. So I put this thing together that is vibrant and permeates society, and I hope is also easy to visualize. I wanted to make it superficially simple enough you could grasp it with a two-sentence explanation, but then have depths and complexities to that could enthral the real geeks. (Like me.) Because that’s how I see real science: life is defined as X–except, well, then there’s viruses. Or geometry: two lines on a plane will never intersect–except, well, on the non-Euclidean side of things…

I wanted my magic to be like that, because it makes it feel real, it allows me to pull some surprises out of my hat, and it keeps me interested for years as I write these books, and then for more years as I talk to fans about them.

I think it’s just a pendulum thing. The LOTR had all this depth in the linguistic side–and none in the magic. Different things fascinate me–and obviously fascinate Blake Charlton and Brandon Sanderson–than what fascinated Tolkien. And I think that’s great.

Like the chicken and the egg, I’m curious about what came first: the magic system or the plot?

I feel like I’m answering “It’s a little of both” on all your questions, but the truth is, they came mostly at the same time. I had the basics of the magic system when I started writing, but it was more complicated and less intuitive. I ran into a brick wall in the plot–specifically, the magical prison I’d made up for one of the characters didn’t cohere. I changed the rules, and it worked. Then I had to go back to some earlier scenes and give up a few cool things because the magic didn’t work that way anymore.

I have to say that it’s actually easier to write once you do have the rules set up, though. And it’s usually pretty easy to fix the problems:

Girl X wants to kill Guy Y. Problem, he’s a 1000 yards away. She picks up a gun. Ah, crap. Matchlocks don’t shoot accurately from a 1000 yards. (The Lightbringer books are set in about 1600 AD.) The answer isn’t to have her shoot from 1000 yards and get lucky; it’s to scratch out that 1000 yards, and put in 100 yards in its place. Voila. Obviously, this will create other problems–now the bad guys will be hot on her heels right after she makes the shot–but those new problems are usually a good thing for a novel.

Though some novels are starting to change the trend, magic is traditionally antithetical to science; in The Lightbringer Series, however, there is a lot of logic inherent to the magic and it follows some very strict rules. How do you find that sweet spot where magic and science intersect?

Great question; if I figure it out in the next three books, I’ll let you know! Honestly, this is something I work on a lot, but I don’t think I’ll know if I did it right until long after this series is done. What I want is for the magic in a fantasy novel to give you the same feeling I get when I walk outside at my parent’s cabin in Montana and look at the stars–there’s pure wonder to seeing the stars so bright, the swathe of the Milky Way, a carpet of galaxies. It’s numinous, mysterious, and yet real, logical, mathematical. We know those stars have fusion reactions, and they obey gravity, and so forth. Thoreau said something about astronomers robbing the stars of their wonder, and he was dead wrong. I think that your wonder can be magnified by your knowledge–like a doctor being endlessly fascinated with life itself, even as he learns more and more.

Whether I’m able to hit that sweet spot with The Lightbringer Series is, of course, a very different question.

How did setting The Lightbringer Series in a Matchlock-era setting affect the story?

Come on, it’s guns and swords and magic all together! It’s just cool!

The real answer sounds trite: it affects everything. You know, if a peasant can pick up a gun and with two minutes of training be able to kill a knight whose armor cost $50,000 and horse cost $100,000 and who’s worked day and night on his killing abilities for ten years–then the world is just different fundamentally. All of society has to adapt. Either you try to outlaw guns to keep the old order, or you hire mercenaries because they’re cheaper, or you invest in really heavy armor and breed strong horses to carry guys wearing it–I mean, the whole array changes. Ditto for, say, transportation. If galleys are the fastest thing on the sea, there are going to be slaves to power them–but if someone comes up with a three-mast ship powered by wind that can go faster and carry more men and guns, things are going to change everywhere.

So different levels of technology are going to change the entire range of acceptable solutions to problems–and to what problems are simply impossible. If I find out the Canadians are finally invading Montana, today I could drive from Oregon and help the resistance–if I have a car. If I’m riding a horse, I’m not going to get there until next spring when the passes open, so, you know, good luck, fellow Montanans.

Your first series, The Night Angel Trilogy was published nearly-simultaneously (each volume one month apart), which, from where I sit, seemed to give a very valuable push to an (at the time) unknown author. Overnight success, by way of years and years of writing. With The Lightbringer Series, you’re writing one volume at a time, but with the guarantee of being published. How has the experience writing a novel/series changed for you since becoming published?

I appreciate you pointing out the years and years of writing that came first, but even then, The Night Angel trilogy really didn’t seem like an overnight success. My initial print run was not huge by any means, and I didn’t get reviewed most places. The fast publication was definitely important–and the cover art just as much so, but The Way of Shadows didn’t hit the New York Times bestseller list (near the bottom, but hey, on it!) until six months after it was published. So for me, the recognition that I was doing well enough to get to keep doing this–as my job–was slow in coming.

That said, the biggest change has been the demands on my time. Where the silence was terrifying before, now the noise is.

There’s also the weight of expectation. When I wrote The Night Angel Trilogy, I didn’t know gritty was going to be the new black. I was just telling the story of whores and killers. To tell that honestly required a certain level of language, violence, and abuse. Thieves and murderers just don’t say, “Shucks.” But having written three books that were gritty, the grit was one of the things some people loved and expected from my work. Doing something different will always disappoint some fans, but doing the same thing over and over is artistic death.

Between The Night Angel Trilogy and The Lightbringer Series, you’ve created two deeply-developed worlds – was it hard for you to leave the world of Midcyru and begin to develop an entirely new one in The Black Prism? Both stories take place on single continents (or, in the case of The Black Prism, a confined area seemingly in the middle of a continent) – are the two series are connected in any way?

Nope. They’re totally unconnected. Which, honestly, I think is harder.

Was it hard to leave Midcyru and develop a new world? Yes. It’s been an incredible challenge to make a world that is completely different. Building new histories, mythologies, religions, cultures, geography, technology, magic, and politics requires a lot of work before you put a single word on the page. Especially if you like expansive worlds and big stories. And then I didn’t want to make things that were reminiscent of Midcyru–I wanted this to be really new.

I really enjoyed it, but it also definitely took longer than I had thought it would.

After the success of The Night Angel Trilogy, was it intimidating when you realized you were going to have to go back and start over from scratch, knowing you had a legion of fans to please? Were there any talks or thoughts of just doing another series set in Midcyru?

Yes, absolutely. I mean, I guess I thought my number of fans was closer to a literal legion–6,000–than it turned out to be, but I definitely thought of writing another book set in Midcyru. I was about fifty-fifty on what to write next, which was a little scary: Hey, Brent, what are you going to spend the next five or six years of your life on?

There was some intimidation. In some ways, The Black Prism counts as my sophomore effort. What if it sucked? On the other hand, I really wanted to prove myself. I didn’t want to be the guy who wrote ninja books. So by writing something new, I gave myself a chance to show what I could do.

Much of The Black Prism‘s thematic structure revolves around family and the often difficult relationships forced upon people by blood. Is this a theme we will see recurring through the series? What made you decide to tackle such a subject?

Absolutely. Honestly, I was reading about the Borgias and Renaissance Italian history and one of the things that fascinated me was the tangled web of loyalties any individual person would have: to their family of birth, their family by marriage, to their city, to their state, to the Church (which was often a state), to God (which sometimes was different than to the Church), to their lovers, to their legitimate and illegitimate children–the list seemed endless. And people chose differently than expected. Women who were expected to join their husband’s family would undercut their husbands to serve their fathers or themselves; popes would openly acknowledge and promote their bastards; bastards who were supposed to just join the church and serve their fathers quietly would leave the church and go on to become military commanders. People poisoned each other, brothers killed each other, and technology and the arts bloomed everywhere.

In the layering of loyalties, I saw layers of conflict. And let’s face it: your family is most likely to bring out the best and worst in you; they know you best and can best exploit what they know. There’s fertile ground for love and hatred to grow side by side–and I think that stuff makes great fiction.

In an essay you wrote for powells.com, you told a story about a fight between you and your brother and a youthful fist fight. I was surprised, and delighted, to see this same scenario show up in The Black Prism and play an important role in the relationship between Gavin Guile and his own brother, Dazen.

In an essay you wrote for powells.com, you told a story about a fight between you and your brother and a youthful fist fight. I was surprised, and delighted, to see this same scenario show up in The Black Prism and play an important role in the relationship between Gavin Guile and his own brother, Dazen.

Are there any other little real life anecdotes in the novel? How much of your own personality and experiences is found in your work?

Probably only one thing that I remember right now: my brother and I had a four year age difference between us, and we were frequently asked if we were twins. Which… well, I’ll just leave it at that.

I don’t often use direct experiences, even that fight was twisted for dramatic purposes. I felt that I could hew a little closer to reality on that one experience simply because two brothers fighting is so universal. It’s iconic, and there’s always this question as the little brother, What am I really willing to do to win this fight? That said, I use the feelings more than the facts of my own life.

On a recent episode of the SF Signal Podcast, you mentioned how you worked on a novel for five years, before eventually scrapping it due to structural issues. What led you to the decision to bench it? And what did you learn from writing that novel that helped you find success with The Night Angel Trilogy?

I was over 250,000 words into the novel and I realized that I was about halfway done. It was the kind of novel I think you’d really enjoy unless you thought about it when you weren’t reading. By which I mean that each individual chapter was entertaining and led to the next one, but the novel as a whole was like wandering through a fog. No shape. I spent a year trying to impose that shape, splitting the story so that it had an ending, and at the end… I just felt apologetic about it. I already thought, I can do so much better than this.

And at a certain point, even though it sucks hard to throw away five years of work, you have to say, is this how I want to start my career? Am I happy enough with this that if someone reads only one Brent Weeks book, and this is it, that I feel it’s representative of what I do? Do I feel it will make them want to read more? I can say yes to the four books I have published now–that book, not so much.

I guess I learned that writing is hard, and I love it. And that I need to have more structure–I’m neither an organic writer nor an outliner, but something in between, and in that novel, I was a little too freeform.

You write some pretty beefy novels. Will we ever see short fiction from Brent Weeks?

Ah, crap. My editor isn’t reading this, is she? I am working on a little project. In general I think my greatest strengths as a writer show themselves better in a longer form–big, well built-up twists and deep characterization. It’s going to be more novella length (for those who don’t know, 17-40,000 words), but I’m writing it with a really visual style, shorter scenes, lots of action, and my hope is that I can publish it as a short story or an ebook through Orbit’s ebook program–and then also get it going as a graphic novel. I’ve been approached about the story and the graphic novel both, but I haven’t sold it yet because I haven’t finished it yet, and if it doesn’t turn out well, I’ll wait until after I finish Lightbringer 2. I’m kind of work-on-one-thing-at-a-time guy. Wish I wasn’t. Anyway, the story is kind of a prequel to the Night Angel books: it centers on this question, how did the idealistic hero Gaelan Starfire become the jaded assassin, Durzo Blint?

I always encourage my interviewees to gush about some of the author they feel are under-read or under-appreciated. Who would be on your list, and why should we be reading them?

If you’re looking for something similar to my work, a guy named Douglas Hulick has a book coming out in May, I think. Debut, gritty underworld, wry humor, starts with the main character torturing a guy–although it does get less gritty from there. I really enjoyed it. On the other end of the spectrum from my writing is Mary Robinette Kowal, whose short fiction I’ve been enjoying. She also has a debut novel out, which is sort of Regency–with magic.

Thanks for dropping by, Brent! Any last words before we send you off to the chopping block?

Yeah, I just wanted to say, Canada, when you do invade, don’t start at Montana. Really. They teach Red Dawn in school.

Seriously, thanks for having me, Aidan, and thanks for not Glen Cooking me. Heck, you didn’t even Vandermeer me! I really appreciate having the chance to talk with you and your audience here. Thanks!

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Aidan Moher, readandfindout.com. readandfindout.com said: RT @adribbleofink: New Blog Post – An interview with @brentweeks, author of THE BLACK PRISM (published by @orbitbooks): http://bit.ly/auxVL0 […]

Man i need to pick this book up! I simply don’t have the money!

The paperback can’t get here soon enough.

Oh yeah, if I’m going to pimp books, I should probably tell you their titles, too, huh? The Douglas Hulick book is Among Thieves. Amazon says it’ll be out April 1st-ish, but you know Amazon. Mary Robinette Kowal’s book is Shades of Milk and Honey.

This is a wonderful interview. I appreciate not only the thoughts about the book and the writing process but also the theories about bloggers and reviews.

I’m waiting for the paperback, I always buy the paperback ones lol but I’m looking forward to it and I think I would buy all the work. Guess Brent really deserves it ;)

Great interview!

For those who are not lucky enough to have caught Brent on tour I just wanted to add that he always comes across as a very happy and friendly guy. He always has a big grin on his face and genuinely seems to have a blast talking with his readers and answering questions.

[…] A dribble of ink: Interview | Brent Weeks, Author of THE BLACK PRISM […]

[…] Interview: A Dribble of Ink interviews Brent Weeks. […]

[…] An interview with SFWA member Brent Weeks, author of THE BLACK PRISM (Orbit Books, 2010): here. […]

[…] Interview: Brent Weeks @ A Dribble of Ink […]

[…] Interview: The Black Prism by Brent Weeks, conducted by A Dribble of Ink […]

[…] Interview: A Dribble of Ink interviews Brent Weeks. […]

[…] Weeks is an awesome interview. 0 […]