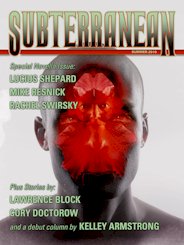

“The Lady Who Picked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” by Rachel Swirsky is a Hugo Award-nominated novella that begins when a sorceress dies and follows her spirit as it is summoned through the ages by a variety of different people and cultures seeking her magic and knowledge. Swirsky’s considered by many to be among the best new voices in genre short fiction, and this novella is yet another piece of her fiction worth reading and, more importantly, examining.

“The Lady Who Picked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen’s Window” by Rachel Swirsky is a Hugo Award-nominated novella that begins when a sorceress dies and follows her spirit as it is summoned through the ages by a variety of different people and cultures seeking her magic and knowledge. Swirsky’s considered by many to be among the best new voices in genre short fiction, and this novella is yet another piece of her fiction worth reading and, more importantly, examining.

The most startling aspect of the story is Swisky’s decision to tell the tale over the course of many millennia. By casting a trapped spirit as a protagonist and narrator, Swirsky is able to cover an enormous amount of time in a relatively small amount of space. One of my favourite aspects of Speculative Literature, especially that which covers vast amounts of time, is its ability to suppose about societies and how they will evolve over time. We see only bits and pieces of each time period, but the juxtaposition of placing a static character in an ever-changing environment and then asking her to try to adapt almost immediately to new ideologies, new races, and new forms of magic, allows Swirsky to explore the regrets of acting blindly on the whispers of endless prejudice and thoughtless bigotry.

“I will not desecrate women’s magic by teaching it to men.”

“How is it desecration?”

“Women’s magic is meant for women. Putting it into men’s hands is degrading.”

“But why!”

Our argument intensified. I began to rage. Men are not worthy of woman’s magic. They’re small-skulled, and cringing, and animalistic. It would be wrong! Why, why, why? Misa demanded, quoting from philosophical dialogues, and describing experiments that supposedly proved there was no difference between men’s and women’s magic. We circled and struck at one another’s arguments as if we were animals competing over territory. We tangled our horns and drew blood from insignificant wounds, but neither of us seemed able to strike a final blow.

“Enough!” I shouted. “You’ve always told me that the academy respects the sacred beliefs of other cultures. These are mine.”

“They’re absurd!”

“If you will not agree then I will not teach. Banish me back to the dark! It does not matter to me.”

Of course, it did matter to me. I had grown too attached to chaos and clamor. And to Misa. But I refused to admit it.

Naeva’s main conflict with these societies, as you can see above, is her hard-nosed and brutally stubborn abhorrence towards men. She was raised in a matriarchal society that treated their men as little more than baby-makers—useless and vile otherwise. It’s not surprise, however, that the societies that she is summoned to through the following millenniums are more liberal in their views toward gender equality. Naeva is faced with confronting her sexism, but it never feels like there is any progress made—she starts out unreasonable, and finishes unreasonable, angry and alone. The ending of the novel hints at redemption, but by then it’s too late for herself and the reader.

Ultimately, I’m not sure that any sort of conclusions are drawn to the questions and problems posed by Swirsky. Of course, humanity’s difficulty with individually adapting from the mindsets and bred-in prejudices of the societies we grow up in can never be solved, or properly explored, in a short novella, but I felt that, ultimately, the explorations of the themes are more of a meandering than a straight drive towards any sort of conclusion. As a story, I enjoyed it immensely, mostly because of the time-travel aspect, and Swirsky’s prose is always top-notch, but as a thematic piece, especially concerning the examination of sexism, it’s a bit of a rocky road. I much preferred Swirsky’s “The Stable Master’s Tale” (REVIEW), which was published around the same time.

[…] these, I’ve read Swirsky’s (REVIEW) and Reynold’s (REVIEW) offerings. Both of them were interesting, but flawed. Chiang’s […]

This is nearly a year later, but I read this last year and thought it was one of the stronger nominees. I enjoyed the meandering aspect to it. I think something that shorter form SFF suffers from is a compulsive need to be incredibly tight and structured. I would have liked the story less if it attempted to rewire itself into making a direct, obvious point about gender issues instead of just letting it be the subject matter.