Some ideas have great power, and in fantastic literature, one of the mightiest of these is the idea of The Hero. The Hero is a very particular sort of creature: it (quite often “he”) is the protagonist of many stories and serves as paragon, savior, and metaphoric proponent/enactor of ideology. The Hero reflects aspirations and serves as inspiration both in the story and to the reader. This can be a useful, evocative device to employ in a story. The problem is, some of The Hero’s admirers use this device to constrain the idea of fantasy and limit the boundaries of imagination that writers and readers use in their engagement with fantasy literature.

Some ideas have great power, and in fantastic literature, one of the mightiest of these is the idea of The Hero. The Hero is a very particular sort of creature: it (quite often “he”) is the protagonist of many stories and serves as paragon, savior, and metaphoric proponent/enactor of ideology. The Hero reflects aspirations and serves as inspiration both in the story and to the reader. This can be a useful, evocative device to employ in a story. The problem is, some of The Hero’s admirers use this device to constrain the idea of fantasy and limit the boundaries of imagination that writers and readers use in their engagement with fantasy literature.

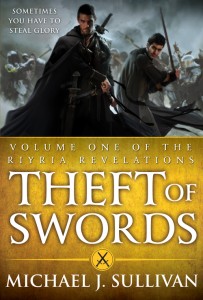

Author Michael J. Sullivan discussed “Fantasy as Fantasy” on his blog recently, and after reading his opinion, I wanted to respond not as a proponent of “the other side” that he establishes, but as a critical reader of fantastika. I was perturbed not by his defense of The Hero, but by his assumption that his position encompassed all of “fantasy” and that fantasy should ideally be Just One Thing. This idea extended not only to the literary genre, but to the very notion of what “fantasy” means. I think that there is far more potential in both of these ideas when we open them up rather than try to set limits upon them.

His thesis is encapsulated in the latter half of his opening paragraph:

“The more traditional “hero’s quest” [is] being abandoned for [a] greater ambiguity that critics call depth. I’ve never been able to understand that because, after all, it’s fantasy, and fantasy is like daydreaming. Does anyone daydream about a miserable world filled with awful people where the dreamer themself is also despicable?”

His then discusses his issues with “gritty realism” taking hold in recent literature and bemoans what this means for society: “[s]eems to me that if we give up on heroes in our fantasies, or on societies that are worth saving, then how can we ever expect to find them in the real world?”

There are three concerns in Sullivan’s post: about the alleged loss of The Hero in fantasy literature, about what he sees as the misuse of “fantasy,” and about “gritty realism” as a symptom of societal malaise. He presents a very clear hypothesis in his piece: that fantasy is about dreaming of better things; that the ideal of The Hero is a necessary component of this, and that we need the inspiration of The Hero to counter the reality around us. I disagree with each of these assertions, and I believe that there is more to fantastic literature, and the very practice of fantasy, that can create far more powerful and fruitful visions for looking at the world around us.

The Campbellian hero is a stock character in high/epic/heroic fantasy fiction, and a series of traditions and a market have grown up around the stories of such heroes. While new trends have appeared and become popular, The Hero has not gone away. Popular writers such as Brandon Sanderson continue to employ The Hero in their stories, and while the field is crowded with more of those gritty, ambiguous types, the classic device remains and shows no signs of disappearing. Sullivan’s concern smacks of the “nihilism” debate that took place earlier in the year, of a disquiet about there being more than one approach to a fantasy story, which implicitly threatens The Hero’s standing as the proper avatar of “fantasy” par excellance.

But fantasy the genre and fantasy the human intellectual capacity are broader than the focus on one iconic idea. “Fantasy” as literary production is not just about a figure of untarnished goodness smiting all in his path. As Richard Mathews noted, even J. R. R. Tolkien’s idea of fantasy was deeper than that: “fantasy is not avoidance of the actual but a means of more complete understanding.” In fact, conflating “fantasy” with “the heroic quest” does a disservice to the very idea of fantasy. The term itself is rich in associations: imagination, illusion, vision, a “picture to oneself.” It is also tied to the idea of bringing something “to light.” Fantasy and daydreaming are not the same thing. Daydreaming is to fantasy as The Hero is to the genre of fantasy: it is one device that you can employ to enliven it and make it productive. To conflate the heroic quest with fantasy, reduce fantasy to the practice of daydreaming, and then contrast it to a demoralizing, dissipative “gritty realism” creates a duality that severely truncates the very idea of fantasy. Fantasy in this formulation is only about dreaming of a better world; realism is the theft of moral certitude and mythic inspiration from our dreams.

Realism is a method of writing fiction; it does not “reflect” the real world, but is the author’s interpretation of actuality. It is not reportage or historical narration; it is a way of translating a person’s perception of how the world works into a literary text. I don’t find Abercrombie’s writing, for example, to be some form of hyper-realism that precisely mirrors today’s world. His storyworld is harsh, dirty, and difficult to survive in. He is not “reflecting” real life, but rather has chosen an approach to his stories that emphasizes not just complexity or ambiguity, but particular applications of these elements to heighten the texture and immediacy of his tale. “Gritty” is as fanciful in its way as white-clad paladins fighting black-shrouded demons; neither is a direct simulation of “the real world.”

These “other worlds” are not “just the same” as ours. They are all illusions, projections of someone’s imagination and vision who complexity is not amoral, but approaching morality from a different angle. They may not fit the narrow range of vision Sullivan advocates in his post, but they are categorically not invalid as fantasies. The hero’s quest is one sort of conjecture, one method of telling a fantastical tale. ALL literature is a fantasy, no matter how closely it strives to mirror someone’s perception of or aspirations for reality. Whether they are personally satisfying to a reader or not has no bearing on their fantastical qualities; equating one sort of story with an entire meta-genre of literary productions limits our understanding of what we are capable of conceptualizing and comprehending through the lens of the fantastic. The fantastic can be edifying, escapist, surreal, inchoate, resonant, or most any other adjective you can think of. That is what makes it fantastic, what gives it the potential to brings things to light.

[…] also wrote a short piece for A Dribble of Ink, a response to a blog post on Michael J. Sullivan’s website about “Fantasy on […]

[…] And John Ginsberg-Stevens responds to this bemoaning on A Dribble of Ink. […]