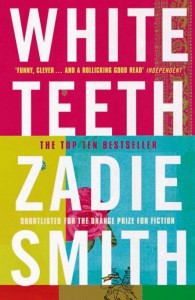

Zadie Smith is best known for writing White Teeth, a many times-nominated novel that takes a Dickensian look at the lives of two North London friends, and along the way explores the ideals and vices of family, multiculturalism and religion. So, it’s with some amount of pride (but mostly deserved happiness) to see her mention Science Fiction, a genre oft-maligned by mainstream critics and writers, with keen interest and enthusiam.

Zadie Smith is best known for writing White Teeth, a many times-nominated novel that takes a Dickensian look at the lives of two North London friends, and along the way explores the ideals and vices of family, multiculturalism and religion. So, it’s with some amount of pride (but mostly deserved happiness) to see her mention Science Fiction, a genre oft-maligned by mainstream critics and writers, with keen interest and enthusiam.

From a recent interview:

‘Only Connect’ is the motto of Forster’s Howards End, the novel that you use as ‘scaffolding’ in On Beauty. You deliberately recreate entire scenes from the novel, from the opening series of letters, to the concert scene, and certain characters are recognizable as being from Howards End. What made you decide to make these references so clear, and are there any other novels that you would like to pay homage to in a similar way?

I’d never do it again. At the time I couldn’t really explain why I had done it. Now, in retrospect, I can see it was an act of tribute, and also a goodbye: a way of laying to rest the influences that dominated me as a child, which were quite conservative literary influences. The thing is, it’s contextual. When I was a fourteen year old all I wanted to prove was that I was English, that I could read the ‘classics’ as well as anyone, that if I passed my exams I had a right to go to this posh university just like any of these posh kids who considered it their birthright. I was outside of everything and I wanted to be inside. That’s the opposite position of a lot of young British writers, who took their Britishness as an undeniable fact and wanted to break out – to French shores, for example, or beyond. I just wanted to prove I had a right to write, to add to the literature of the country in which I found myself. Hence the Forster, hence the Eliot, hence the Woolf, hence all of that. It was personal and political. I was absolutely determined that no-one was going to say to me “Oh, they only let you into Cambridge out of some kind of working-class/race affirmative action.” I wanted it to be clear that I could do the work as well as the next Etonian. So my childhood was all about being this good student, because I had no money, and without the grades I knew I wasn’t going to get out of Willesden. To me ‘wanting to be a writer’ meant first passing these A levels. I knew I was fucked without them.

It was only when I got to college that I realized I had concerned myself with a lot of stuff my peers weren’t concerned with. A friend said to me at the time that I was ‘fatally out of step with my generation’ – but in a way I think that embedded Nerdism, being more familiar, at that time, with Milton than Bukowski or whatever, helped me. It gave me a very solid foundation.

Anyway, the Forster thing was part of that out-of-stepness. So then it was so strange to find myself published and hear some people saying ‘you only got published because you’re trendy and black.’ I felt black, but not trendy. But of course, if people want to see you that way, you can’t win with them – trying to ‘prove yourself’ to people like that, I see now that it’s a hiding to nothing. I try and write the best books I can and people are of course free to like or dislike them, but there will always be people who say ‘she got published because she’s black’. Consider for a moment how it would be possible to win this argument? You can’t win it. The only objective test I can think of is if ten young white writers and I submit anonymous essays or stories to a board of readers convinced that blackness is an enormous secret advantage in the publishing industry. Would they be able to spot my affirmative-action prose? Is it really so poor next to my white peers? Maybe. We should set up that test somehow.

No, the real, unquestionable advantage was Cambridge. A publisher wrote to me in my final year because he’d read something of mine in a Cambridge publication. That was the absurd luck and privilege of the institution. All I can say is that I worked my arse off to get into that institution. And I felt guilty, because I had so much luck. The only way I could justify my luck to myself was to try and write as well as the next guy. What else can you do?

This is a long way of saying that On Beauty was the end of all that for me – of trying to get people’s approval by writing myself IN to this English tradition. I just don’t care any more. All I can do is continue to work very hard on my little projects, taking in any influence I feel like, and not fearing subjects that interest me. 19th century Jamaica interests me. The 70’s Black Power movement in London interests me. The feminist lesbian movements of the 60’s and 70’s interest me. At the moment, sci fi, speculative fiction, interests me enormously. I’m so excited now about the next decade. I feel free!

As fans of genre literature, we all know how wonderful it can be. We know the beauty and the possibilities presented by the creative minds who have helped define the field; but we also know how difficult it can often be to convince readers outside the genre to give it the consideration and credit it deserves. With advocation from authors like Smith, however, we’re one step closer to shedding that undeserved reputation and moving into the spotlight among ’proper’ literary novels and novelists.

This isn’t the first time a mainstream or non-genre author has dabbled with genre fiction, of course. Iain M. Banks, author of the enormously popular Culture novels, has also penned over a dozen mainstream novels under the name Iain Banks, many of which have found success similar to his Science Fiction; Margaret Atwood, the first lady of Canadian literature, is a Science Fiction writer in disguise; and Michael Chabon has won both a Hugo Award and the Pulitzer for his work.

And that’s not to mention the many successful “mainstream” authors who are writing speculative fiction another a different name. Because, really, are Dan Brown, James Rollins (who writes full-blown Fantasy under the name James Clemens), Carlos Ruiz Zafon, or Diana Gabaldon writing novels that are so drastically or spiritually different than many of the novels that clutter Science Fiction and Fantasy shelves?

So, my question to you is, which ostensibly mainstream author(s) would you like to see try their hand at genre fiction? Would you like Michael Chabon to turn his hand fully over to Fantasy? Or should Bernard Cornwell perhaps leave real-world history behind for a more speculative history? Would you be more interested in an author like Zadie Smith, whose past work offers little-to-no resemblance to recognizable genre fiction, try her hand at it; or should the mainstream authors stick to what they’re good at and leave the fun stuff to the (nerdy) professionals?

I’d love to see a more post-modern writer tackle it. How would Don DeLillo’s Underworld have been different set in an alternate reality? Trippy.

I am all for this sort of thing, not because it might open up SFF to a wider, perhaps formerly close-minded audience or because it might free the genre from the term “ghetto”, but because my experiences with mainstream authors crossing over into genre have all been positive. I approve for selfish reasons. I don’t care about genre climbing up in the world and getting a better name for itself, I just want to read good books.

Well said, James. I agree, 100%. Well, except for Modelland by Tyra Banks. She’s a mainstream author, right?

Modelland appears to be her first attempt at fiction, which makes her pure genre.

Anything that helps take the stink of speculative fiction in the minds of “mainstream” readers is fine by me. But I wonder if Michael Chambon’s work in our field inspired many of his readers to explore further in genre and discover many equally talented writers, or if they only read his fantasy because they already respected his name on a cover? Just wondering.

That’s a very good question, Lynn. Frankly, though, I’m not sure I’d like the answer.

It’s not a question I’m going to answer because it’s not a question I think we should be asking. The same goes for Mind Meld’s like this. They are questions that reduce and limit the potential for art by suggesting it is something akin to a production line. I don’t want my favourite mainstream writer to write a science fiction novel, I want them to write whatever they want to write. (I’ll cop to a bit of hypocrisy here because I sometimes want children’s authors to write adult novels but I’d argue that is slightly different.)

Having just written a column on the problems that genre can create, I’m not sure how to answer your question, Aidan. I wish more authors in general would realize that borrowing tropes & textual strategies and crossing boundaries can enrich their fiction and potentially draw readers from different communities to their work.

I think another important person to put in the mainstream, respected authors who have written sci-fi list is Doris Lessing, Nobel Laureate and former Guest of Honour at the World Science Fiction Convention.

Love this form of fiction. It’s fusion fantasy: Throw any genre together in a blender and hit high.

I’d like to see Victor Lavalle take his toe out of the fantasy realm in his award winning literary fiction and take the plunge. For a while he was talking about featuring a zombie, but he went a different way in The Big Machine, his last and scrumptious book. Totally recc.