“Urban Fantasy” is a hot term these days. You hear it used to describe everything from Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse books to Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files. It encompasses the work of authors from Patricia Briggs to Kim Harrison, from Ilona Andrews to Kevin Hearne. With such a diverse range of talent, the definition quickly loses meaning. There isn’t a whole lot that’s urban about the sleepy, small town of Bon Temps.

“Urban Fantasy” is a hot term these days. You hear it used to describe everything from Charlaine Harris’ Sookie Stackhouse books to Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files. It encompasses the work of authors from Patricia Briggs to Kim Harrison, from Ilona Andrews to Kevin Hearne. With such a diverse range of talent, the definition quickly loses meaning. There isn’t a whole lot that’s urban about the sleepy, small town of Bon Temps.

But that’s okay. Because urban fantasy has never been about urban settings. It’s about *contemporary* settings. It does a very simple thing: it takes the modern world, the one we live in every day, and ask the question, “What would this be like if magic were real?”

If the genre’s popularity is any indicator, that question has traction. Fantasy has, for much of its lifespan, been dominated by ancient and medieval settings. Many of the most enduring works in the genre, from Tolkien to Brooks to Feist, are set in pre-gunpowder, pre-industrial revolution worlds. But readers don’t ride to work on horses, hunt deer for dinner, or carry a sword to fend off the occasional Orc raid. Contemporary fantasy’s popularity suggests that many readers like to dream about the impossible right in their own backyard.

And here’s where you can run into trouble writing contemporary stories. The same thing that makes a contemporary setting resonate so strongly with the reader may also piss them off: Ownership.

Back when dinosaurs roamed the earth, I wrote an article about the Enola Gay Controversy. The kerfuffle surrounded the Smithsonian’s decision to exhibit the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The Air Force Association and the American Legion hit the roof, claiming that the exhibit focused too much on the casualties of the explosion, and not enough on the bomb’s critical role in ending the war and potentially preventing even greater loss of life. The shit-storm got so bad that the director of the Air & Space Museum was forced to resign.

The root of the controversy could be found in that sense of ownership. People who lived through the Enola Gay bombings, both Japanese and American, were watching this exhibit. They felt ownership over a story that held deep meaning for them. They cared deeply about how it was told.

It’s tougher to stir this level of passion over the Four Lands or Middle Earth or Xanth, because nobody has any real experience with those places. It’s hard to feel like you own those stories. But Harry Dresden runs his cases in modern day Chicago, and so I wasn’t surprised to see a minor blow-up when Jim Butcher was accused of white-washing the neighborhoods depicted in the book. Readers grow-up, live and work in modern day Chicago, and care passionately about how their home is presented.

I’ll be honest. This scares the crap out of me.

I’ll be honest. This scares the crap out of me.

No matter what an author intends, once the work is written, published and sold, it’s out of the author’s hands. You can’t control how a reader will interpret your work, nor should you try. And when you are writing work that sits right where people live and eat and sleep, you are running the risk that they will take something from it that you didn’t intend, will assume things about you that aren’t true. That’s scary.

But in the end, you can’t let that stop you. Your responsibility as a writer is to create the most compelling story you possibly can. Compelling stories invoke passion, and passion can be directed in a variety of ways, including straight at your face. It’s a hazard of doing business. But I’d argue that if you let it stop you, well, then maybe this isn’t the right line of work for you.

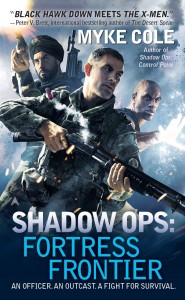

My SHADOW OPS series is about the modern United States military. That means there are roughly 1.5 million people (not counting their families, friends, contractors, civilian counterparts, etc…) with a dog in the fight. They have every reason to believe that I’m telling their story, whether I intended it that way or not. I’m in the military, so it’s my story too, but that doesn’t shield me from the passions my depiction might inflame. When Control Point hit shelves, I chewed my nails down to the quick waiting for someone to shout, point a finger. I’ve done fairly well so far, but that concern never leaves me.

My SHADOW OPS series is about the modern United States military. That means there are roughly 1.5 million people (not counting their families, friends, contractors, civilian counterparts, etc…) with a dog in the fight. They have every reason to believe that I’m telling their story, whether I intended it that way or not. I’m in the military, so it’s my story too, but that doesn’t shield me from the passions my depiction might inflame. When Control Point hit shelves, I chewed my nails down to the quick waiting for someone to shout, point a finger. I’ve done fairly well so far, but that concern never leaves me.

Because I don’t want to piss people off. I don’t want them to focus on assumed subtexts and agendas. I want them to sit back, relax, and enjoy a rocking adventure.

I’m pitching a new novel right now. The protagonist is a US Navy SEAL. There are real SEALs out there, working under conditions I can only imagine, pursuing objectives that would have me curled up in the fetal position. When I put the SEAL label on a character, even in an entirely fantasy world, I step into their wheelhouse. Like it or not, I risk the story resonating with them in ways I’d never intended.

I’m terrified.

And I’m doing it anyway.

Because if there’s one thing SEALs would understand, it’s the old salt of their counterparts in Britain, the SAS.

Qui Audet Adipiscitur.

Who Dares, Wins.

+1 for the Latin. :)

I do wonder if the use of imaginary locations in some contemporary/urban fantasy is a way for writers to avoid pissing people off on geographic and social grounds. “I can’t believe that new novel by Myke Cole, I grew up on Staten Island and I *know* New Yorkers don’t take Staten Island seriously.” .

So, if you make “New Deptford” as a city, you can create an urban fantasy set in the modern day, and make stuff up without getting people angry.

To paraphrase Larry Niven

There is a technical term for those who assume the beliefs and outlook of a character in a work of fiction are that of the author. That technical term is “idiot”.

It’s an interesting point and not one I’ve considered. I think I was reading fantasy and science fiction long before anything else, so when I started reading Urban Fantasy I never expected the setting to be completely accurate and I did expect the author to change the ‘world’ to their own vision for the story. It’s never bothered me before, even novels set in places in the UK I know well. People confusing fiction with non-fiction perhaps?

I can’t help but wave my arms around in confused anger. Why can’t a museum director present something whatever the hell way he wants to, and why can’t people just disagree and have a public debate, and see it as an opportunity to study all aspects of an issue? Why must it end with someone’s career taking a hit? [Full disclosure: I have a friend who is a curator there – in fossils, not air & space.] Is there any such thing as respectful public discourse.

Hey Myke, Can you tell us more about the Navy Seal story? Gotta dig those guys, baddest warriors on the planet!

Off topic but I just wanted to thank you for your books Myke. I brought Control Point recently and I am enjoying it so much I have Shadow Ops loaded on the reader and ready to go next already.

As to respect and public I find those words are mutually exclusive a lot of the time these days……

Presenting some of these questions as who has/claims “ownership over a story” is an interesting take, and one I’ll be thinking about, so thanks. I think it works better in the Enola Gay/US military examples that you gave, rather than in the Jim Butcher Chicago example. Because that example isn’t just about people caring about how their home is presented, and all sorts of people having different interpretations of it.

Rather — as I understood it — it’s about who is being included in the story. So it’s not just about who owns the story, but is the story telling the dominant narrative of the majority or the unheard/under heard story of the minority? And critiquing an author for going along with a dominant narrative, even in contradiction to reality.

People don’t just feel that they “own” a story about Chicago because they live there. They justifiably feel a right to be present in stories, especially stories about cities and neighborhoods that they exist in currently, and especially given a history of being excluded.

[…] was also hosted by A Dribble of Ink for whom he wrote a fascinating article entitled ‘The Peril of the Contemporary’, in […]

[…] little while back, I wrote a piece titled “The Peril of the Contemporary.” I say a lot of things in that guest post, but the most important takeaway is this: I firmly […]