Art by Evan Lee

The great old stories break and bend rules modern audiences take for granted. For example: Journey to the West, which I talked about last month, is a story of high-flying magic, transformation, kung fu, divine war, and so on—that, for all its epic scope, reads more like Sword and Sorcery.

That is, to borrow Liz Bourke’s definition of S&S: Journey to the West is a story of encounter, in which central characters going about their daily business keep running into strange, fascinating, terrifying things—and befriending them, or beating them about the head and shoulders, or both.

By contrast, let’s talk about one of the best war-and-intrigue novels of all time, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. At first glance, Three Kingdoms seems an epic fantasy, in that it describes the fall of a massive empire through the lens of central characters with dynastic ambition. But, though set in a time of miracles, Three Kingdoms relies on the traditional Sword & Sorcery mix of cleverness, combat, and betrayal rather than prophecy or magic.

Fight for the Future

The empire, long united, must divide. Thus it has ever been.

Three young men meet in a peach garden in their nation’s twilight. One’s a local farmer. One’s a scholar, on the run because he killed a town bully. One’s a poor minor noble—a cousin to the throne so distant that his surname is their only real connection. The men have only one point in common: they are patriots. Together they pledge brotherhood, share a cup of wine in the shadow of the peach blossoms, and set out to change history.

This is the first chapter of a hundred-twenty chapter epic set in the twilight years of the Han dynasty, which ruled many of the lands now called China from 206 BCE to 220 CE. In proper epic fantasy fashion, the book starts with signs and portents: green phantasmal serpents coiled around the imperial throne, hens transformed to roosters, dark clouds boiling up to fill ancestral shrines. In the far West, an evangelical rebellion rises, with a yellow-turbaned leader with magical powers who believes he has been appointed by Heaven to overthrow the corrupt dynasty. The Emperor calls for recruits, and the call reaches the countryside where our heroes first gather.

That summons brings together Liu Bei the noble, Guan Yu the scholar, and Zhang Fei the farmer, drunk, butcher, and all-around stalwart. They raise a small force of men, and set off to save the world.

That summons brings together Liu Bei the noble, Guan Yu the scholar, and Zhang Fei the farmer, drunk, butcher, and all-around stalwart. They raise a small force of men, and set off to save the world.

Over the next hundred-twenty chapters, we follow these men, their comrades, their enemies, and their children through warfare, treason, the downfall of the dynasty, and the rise of a new era. From relative obscurity, the three brothers rise to govern a city, command a province, and at last, to build a kingdom.

Meanwhile, the scheming genius poet-tactician Cao Cao and the conflicted general Sun Ce, gain power; Cao, the adopted son of a corrupt eunuch, maneuvers his way to the heart of the Imperial court where he seizes control of the Emperor, while Sun Ce flees to his ancestral homelands the south, branded a traitor. The action swings back and forth from Liu Bei and his friends, often one step ahead of certain doom, to Cao Cao, who smoothly assumes control of the empire, and the Sun family, entrenched in the southlands and preparing for war. As Liu, Guan, and Zhang gain followers, they challenge Cao Cao’s authority—to their own peril, as Cao marshals a crushing assault into the south.

Three Kingdoms effortlessly wheels between court intrigue, battlefield grit, music-hall seduction, and fraught debate over mulled wine. This book bursts with tactics, maneuvers, betrayals, and crossed motives. The question of loyalty spins at the story’s heart: what does it mean to be a loyal subject, son, daughter, or brother? When a nation you love starts to fall apart, how do you save it, and when is it time to give up on saving and build something new? Cao Cao is cast as a villain in much of the novel, but he’s the one fighting on the side of the Empire, at least nominally; of course, he’s installed a puppet Emperor and holds all real power, but when he fights, he’s ‘under the standard’ as it were.

That question of loyalty gives the quietest scenes in Three Kingdoms thrilling power. On my first read of Three Kingdoms, I was stunned by the martial heroics, but a simple moment when Liu Bei and Cao Cao share a drink in a plum garden stuck in my mind like a splinter under my fingernail.

If you come to fantasy for strategy, chivalry, loyalty, and the destiny of nations, look no further.

Where’s the Romance?

While the traditional translation of the Chinese title 三国演义 is Romance of the Three Kingdoms, we’re talking about Romances of the old school, romances like the Song of Roland—stories about heroes, basically. There’s not much of a modern romance here. For that, depending on your tastes, you’d be better served seeking out Dream of the Red Chamber, or (and here I blush) Jin Ping Mei.

The title literally translates to Three Kingdoms Historical Novel (yanyi is a genre name, composed of the character for ‘perform’ and the character for ‘righteousness’, though this kind of analysis is dangerous with Chinese words). Why ‘historical novel’? Well, Three Kingdoms is based on the true history of the fall of the Han dynasty. Most of its characters are historical, and the battles it describes, happened. The story’s invention lies in its characters, which had been filled through a thousand years and more of folk tradition by the time the writer sat down to work. For example, Cao Cao in the novel is such an overwhelmingly cool villain that the Chinese expression for ‘speak of the devil and he appears’ is literally ‘speak of Cao Cao and he arrives.’ Historical sources don’t paint the man as anywhere near that bad.

Bromance of the Three Kingdoms, or, A Brief Note on Gender & Historical Values

Three Kingdoms, with its more serious and realistic subject matter, offers a modern genre reader more values dissonance than does a lighthearted romp like Journey to the West. Many central characters come off as strange, if not downright bad, people by modern standards—Liu Bei, especially, who’s set up as the ideal king, abuses his son, and his views on women can seem backward at best. Women in Three Kingdoms are often property, collateral damage, or temptresses, with a few exceptions. This book contains a lot of great stuff, but it has baggage too.

Art by Daniel Dociu

How to Read

We have a few complete translations of Three Kingdoms, of which I’m most familiar with the Moss Roberts translation. Roberts is very readable, and includes tons of footnotes for the interested scholar. Also, the paperback volumes to which I’ve linked include a sheaf of traditional prints of the major characters in the frontmatter, which help keep the many characters straight.

There’s also an older translation by Brewitt-Taylor. I haven’t read this myself, so I can’t speak for or against it outside of the fact that Brewitt-Taylor uses the old Wade-Giles Romanization system, the one with all the apostrophes, which is pretty out of date these days.

Googling around looking for resources for this article, I discovered ThreeKingdoms.com, a website that features the (public domain) Brewitt-Taylor translation, annotated and revised, with the W-G Romanization updated to Pinyin. I haven’t reviewed this closely but it might be a good way to taste Three Kingdoms without diving in. Use at your own risk!

I really, really wish I could point you toward some reliable abridged versions, but I don’t know of any. The Three Kingdoms story is more interlaced and complicated than Journey to the West, with a much larger core cast; it’s hard to imagine what you might trim to abridge.

Have Your Note Cards Ready

I’ve mentioned only the central players in of Three Kingdoms because this is a book with a Cast of Thousands (literally). For serious: if you think George RR Martin follows a lot of characters, you have no idea. This book stretches through two generations, and the principals spend the entire time accumulating enemies, allies, and offspring.

Secondary characters are often even more fascinating than the leaders; many have become cultural touchstones for the nations that include Three Kingdoms in their cultural history. Diaochan, the chorus girl who destroys an empire, is one example. Lü Bu, fierce warrior, doomed lover, dupe of kings, is another. Zuge Liang, humble Daoist genius sorceror-tactician, bearing his fan, out-Holmeses Holmes a thousand years before Conan Doyle. On top of these we have one-eyed giant Xiahou Dun, charismatic general Zhou Yu, green eyed Lord of the Southlands Sun Quan, and a host of others to cross the eyes of the most dedicated neophyte readers.

Fortunately, the internet is here to help! Most characters can be easily identified with a Wikipedia search, or by using one of the online Three Kingdoms jargon files. Kongming.net features a searchable list of all the more than two thousand (!) commander characters, for example.

Three Kingdoms in Pop Culture

Three Kingdoms, like Journey to the West, has spawned a host of popular culture interpretations, some more accessible than others. I’ll do my best to hit the highlights here, but there’s so much that I have to apologize in advance for everything I know I’ll miss.

Film

Okay, confession time—a big part of the reason I’m writing this article is because I know it will let me convince more people to see Red Cliff. I describe stuff for a living and trying to tell people how awesome this movie is often leaves me speechless. John Woo, master of the two guns, directs an absurdly massive dramatization of ten key chapters of Three Kingdoms, detailing the lead-up to the pivotal battle of Red Cliff. This isn’t a strict adaptation of Three Kingdoms, drawing off some more modern historical research to supplement the novel’s characterizations (which, as I understand it, often portray the Sun family and their allies as being less cool than history suggests they were), but who cares.

You know how, after a roleplaying campaign where all the characters are max-leveled, fighting their way through armies and changing the destiny of nations while dealing with deep-seated emotional issues, you find yourself wondering why so few movies combine depth of characterization with over-the-top martial arts superheroics? Red Cliff is that film. Kung fu action. Tiger hunting, Strategy. Intrigue. Trust. Betrayal. Epic Qin duels. Victory achieved by cleverness and perseverance. The triumph of Intellect and Romance over Brute Force and Cynicism. It’s all here, portrayed by an excellent director and top-flight talent. And, man, I don’t care what your sexuality, if you don’t have a crush on Takeshi Kaneshiro and Tony Leung at the end of this movie, you are officially dead.

SEE THIS MOVIE. Red Cliff was released in a much shorter (as in, only two and a half hours) edition for American theaters—that’s the one I saw on the big screen. It’s great, and if you search for “Red Cliff Theatrical Version” you’ll find it, but I’m going to link you now to the Red Cliff International Version, which is um four hours and forty-eight minutes long but SO WORTH IT. Barbecue a slab of something delicious and put this on one Saturday when you have nothing else to do. Gather friends, and fall in. The film actually feels tighter at 288 minutes than at 148; the extra two and a half hours improve pacing and invest us more in the characters and their struggles.

My one caution: if you don’t know Three Kingdoms already, familiarize yourself with the central characters before watching this film. You’ll enjoy the thrill of recognition, and the first ten minutes will be even more awesome than they are already.

Weirdly, considering its greater length and density, Three Kingdoms lends itself very well to film adaptation. There’s so much story there, and so many notable events, that it’s relatively easy to pull out one chapter, or three, and dramatize them. The 2011 film The Last Bladesman, starring Donnie Yen as Guan Yu, for example, adapts a critical event from the life of scholar-spearsman Guan Yu.

Television

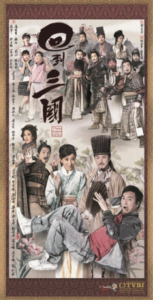

Because Romance of the Three Kingdoms is much less about episodic adventure than Journey to the West, it didn’t lend itself as well to old-form Western serial TV. Nevertheless, adaptions are common on Chinese television, the most recent (it seems) being the high-budget Three Kingdoms released in 2010 and directed by Gao Xixi. The Three Kingdoms characters are giants of the literary canon—Guan Yu is literally regarded as a god—and perhaps because of that severity, there are also a decent number of silly adaptations. Hong Kong’s TVB has a series called Three Kingdoms RPG about a 21st-century Hong Kong Real Time Strategy gamer kid who gets zapped by a time warp and sent back into the Three Kingdoms era, where he becomes a buddy and assistant to master strategist Zhuge Liang. On the more “huh” side, there’s Ikki Tousen (warning: TV Tropes link), the anime series where all the Three Kingdoms characters are, um, improbably proportioned Japanese schoolgirls in a massive fighting tournament / gang war in modern Tokyo, which tournament apparently involves copious fanservice. Eek. Full disclosure: I’ve never seen Ikki Tousen, so maybe it’s great, but it’s also sort of infamous in Three Kingdoms circles. If anyone knows of an awesome Three Kingdoms anime, let me know!

Video Games

No surprise, a 120-chapter novel about battles and heroes lends itself absurdly well to video game translation. The most easily available games in the United States are the Dynasty Warriors series, in which You the Player assume the identity of one of the many, many commanders on one of the three sides of the war, and fight your way through key battles, possibly changing history! I find the Dynasty Warrior games dangerously addictive, and really capture the book’s epic scope—you’re basically in an RTS, only you have no control over anything but a single disgustingly overpowered superhuman warrior. In my opinion, these games are best played splitscreen with a friend, which allows for conversations like “I’ll hold our right flank; see if you can sneak behind enemy lines and kill their general!” And the more of those conversations we can have in life, the better.

Summing Up

If you’re the kind of fantasy or science fiction fan who thrives on politics and intrigue and war, if you’ve memorized all the characters in A Song of Ice and Fire, if you wish the Illiad contained more grand strategy or if you’ve ever thought through Arthurian geopolitics — Romance of the Three Kingdoms is your book. Even if that’s not normally your speed, this book contains some of the coolest characters and setpieces in world literature. I’ll go out on a limb and say anyone who can read (or watch) the story of Zhuge Liang borrowing arrows from Cao Cao without cracking a smile is constitutionally insensitive to trickster tales.

If anything I’ve written here has intrigued you even a little bit, snag a character list and a translation, and dive in.

Oh, and seriously. Watch Red Cliff.

Yep,I own the 2-disc version on DVD :)

“And, man, I don’t care what your sexuality, if you don’t have a crush on Takeshi Kaneshiro and Tony Leung at the end of this movie, you are officially dead.” I’ve had a crush on Tony Leung since I was about 10, does that make me alive AND cool? ;) Spot on re: Red Cliff, which reminds me it’s time for another watch — and I haven’t seen the 4-hr version yet.

@Paul – Excellent!

@Drey – Alive and cool just begins to cover it! And I’d definitely recommend the four hour version. Lots of character motivations make more sense—Sun Shangxiang, Zhou Yu, and Zhuge Liang all get a good deal more screen time & their final arcs (especially Shangxiang’s) make more sense as a result.

Have to third (fourth? tenth?) the recommendation for the 4+ hour version of Red Cliff. It’s fabulous on every level. No. It’s magnificent.

I have not (sad to say) read The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (although we have a copy in the house). Fortunately I watched the film with my son, who has read it, and he gave a running commentary so we could keep track of things, people, background, and so on.

[…] Ink, I continue my blog post series on non-Western fantasy source material with a gigantic essay on Romance of the Three Kingdoms that is, among many other things, a naked plea for everyone on the internet to just watch Red […]

[…] Max Gladstone talks about the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. […]

Red Cliff is pretty fun to watch, but in my opinion it’s been severely Hollywood-ified from the original, focusing too much on romantic drama and the power of friendship rather than conquest, betrayal, and the vagaries of history. If you’re interested in a watchable version that stays closer to the spirit of RTK, I’d recommend Three Kingdoms 2010, whose characterizations are much deeper than Red Cliff’s and which covers a much longer period of time. While there’s no official dub into English, fans have translated and subtitled the entire series, and it’s watchable on youtube.

Wow that would be a read to remember.

The Ravages of Time is an excellent manhua adaptation, but I admit I don’t know of any good anime adaptations. And I have to agree with Naz; Red Cliffs is definitely visually appealing, but a bit too Hollywood for my tastes. The ending scene, especially, is pretty jarring when you remember that the struggle for Jingzhou that comes next in RTK causes the deaths of half the protagonists at the other half’s hands. I prefer the 2010 TV adaptation for its interpretations of events and characters on the whole. While it cuts out and/or reduces the roles of some characters, it uses the extra room productively; the show has my favorite versions of many of the main characters, and I found myself cheering and shedding tears for characters I didn’t even know I could cheer and shed tears for, like Lu Su. The adaptation has its flaws, but it’s still one of my favorite TV dramas, period.

[…] the meantime, Max Gladstone is back over at A Dribble of Ink, sharing his thoughts on China’s epic Romance of the Three […]

I’m embarrassed to say that while I’ve read the Roberts translation of Rot3K and loved it, I’ve not yet watched Red Cliff. This despite the fact that I’ve use Zhuge Liang’s technique for summoning the East Wind in two fiction projects of my own.

Love, love, love this story.

[…] Gladstone’s “Broader Fantasy Foundations” series has two new-to-me entries: Romance of the Three Kingdoms and […]

Someday I’ll get around to reading it, but until then I’ll just play Dynasty Warriors 6. Unlocking Lu-Bu and playing his campaign is half the fun.