I get the question “Why insects?” quite a lot. My stock response depends on how flippant I’m feeling at the time, but comes in two flavours. One is all about lofty literary ideals and exploring the human condition via the chitinous mirror that is insects. The other is “I just like insects.” Both are true1.

The lofty literary business is a thing, though. There is a genuine tradition, mostly a Central/Eastern European one, of using insects to examine human nature. Kafka’s Metamorphosis, of course, but also the Insect Play by the brothers Capek, and Viktor Pelevin’s Life of Insects. Even the ant section in T.H. White’s Sword in the Stone is worth a mention2.

These are all great works, but for me – the lover of insects – they share a problem. Their portrayals are all very negative. When Samsa wakes up as a cockroach3, it is both to the revulsion of his family and peers, and to considerable physical difficulty just getting around in a human world4, and the various insects in Pelevin and Capek are shown as human, but the worst of what humanity has to offer – selfish, rigid, murderous, warlike. They are an object lesson in where we’ve gone wrong as a species.

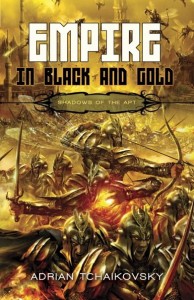

Art by Chris Hill

They are the swarming hordes, whose purpose is no more than to overwhelm and devour – and we, the heroic humans, are free to slaughter them in their thousands.

Elsewhere in genre fiction insects and their kin are simply a convenient shorthand for the worst possible evil. They are the swarming hordes, whose purpose is no more than to overwhelm and devour – and we, the heroic humans, are free to slaughter them in their thousands, because they come in their millions, and they all look the same, and they come over here, taking our jobs and ogling our women, and… Well yes, just like stormtroopers, zombies and killer robots, insects are a perfect way of dehumanising the Other until you can kill them without conscience or remorse. Who cares about insects, after all? For a perfect illustration, look at the poor bloody Geonosians in the Star Wars prequels. These are the insect guys in Attack of the Clones who have that arena thing where the big fight takes place, and they are also the ones who manufacture their cannon-fodder surrogates, the battle droids, for the Trade Federation. The Phantom Menace already substituted battle droids for living enemies to make the mass slaughter of the baddies more palatable, and when Anakin & co arrive on Geonosis they pick up with the Geonosians exactly where they left off with the robots. The insect-people (many of whom are unarmed and protecting their home) are simply fair game. There’s no Sand People moment of Dark-sidedness in hacking the crap out of them, they’re just there to die.

World of Warcraft has used insect-like races three times now to signify ultimate evil – detailed and nuanced insect races, in fact, but in the end they always reduce down to the nihilistic swarm. Tolkien – well, seriously, Tolkien I can only assume to be an arachnophobe5. Orcs will kill you, but the spiders, with their webbing and poisoning of the dwarves, promise a fate worse than just being hacked about – not just evil but unsportsmanlike too – un-British. I could go on.

Art by Matthias Utomo

It’s worth pointing out Starship Troopers here, as a film that subverts the trope – the subtext is very plain about who’s invading who, and who the real monsters are, and highlights the ludicrous double standards of the Space Marine/Spartan etc. style archetype – in that it turns the human protagonists into exactly what is being demonised, a vast horde of identical emotionless Perfect Killing Machines. Leonidas and Master Chief and Leman Russ know their followers are individual heroes. Nobody thinks to consider that Insect Monster Queen S’zzzzrrptjk might think exactly the same about her myriad brood.

Art by Amelia

For some reason, the world of superheroes appears to be gratifyingly ‘colour-blind’ towards insect symbology. Spiderman, Blue Beetle, Ant Man, Wasp, all heroes, and nobody bats an eyelid. And of course the general insect-phobia I’m talking about is a very western thing. Plenty of New World, African and Asian cultures, for example, are full of positive insect role models, but for the progeny of Europe – that continent most free of actually threatening invertebrates – insects (other than bees, butterflies and ladybirds, I guess) are basically the Devil.

So this is where I came in. Because I liked the Geonosians and the Silithids and those wretched bad guys in Star Fleet, whatever they were actually called. I wanted to write a version of Metamorphosis where Gregor Samsa wakes up as a cockroach and it’s aces, best thing ever. I wanted to do insects that weren’t slaves to a hive mind67. And so, for my fantasy series, Shadows of the Apt, I came up with the insect-kinden – human nature being explored through insect nature8.

I’m not talking about the Art – the ability the kinden use to take on insect powers like flight. What that lends to the narrative is a whole different story, mostly to do with how your world changes when magic (not that the kinden think of it as magic) is a universal. However, each of the kinden has a particular nature that has developed under the influence of its arthropod patron. Individual characters may conform or kick against it, but there is certainly an archetype, for better or worse.

And that last is the key: better or worse. I can be as pro-bug as I like, but being rose-tinted about it would harm the narrative. Each of the kinden has its good and bad side, inextricably intertwined. Each has its own identity, but in a sufficiently flexible and nuanced way that, I hope, they avoid the ‘fantasy/SF race trap’ where alien or fantastic species basically have one personality trait and one thing they’re good at, and every one of them is like that, and does that. If there is a key to why the series – and the world – has found its readership, it’s probably this.

Beetles endure, for example. That’s an in-setting proverb, even. Just as beetles are found everywhere in enormous variety, the Beetle-kinden adapt and thrive – inventive, tough and flexible… the flip side of which is that there are plenty of examples of that becoming a moral flexibility – greed and self interest promoting the survival and profit of the individual no matter what9. Ant-kinden are cohesive and loyal, strong and self-sacrificing, but only if you’re one of them. Their cities tend towards martial isolationism, their technology towards reliance on the tried and tested rather than allowing innovation from outside. Spiders are elegant, creative, deceptive and often too clever for their own good. Wasps, the main antagonists, are militaristic, intolerant and parasitic, but also courageous, passionate and ambitious. And as noted, these are just the stereotypes. There are plenty of renegade Ants, noble Wasps, loyal Spiders and rigid Beetles in the books.

But things come full circle. I do go one darker and play with the most negative associations of insects and their kin, having firmly established my credentials as a champion against that. In a sense, the trope would be incomplete if I didn’t acknowledge the stereotype somewhere and put my own spin on it. And so we come to Seal of the Worm, in which the worst is made plain, and is revealed to be not just an invertebrate characteristic, but a human one. To write of the need of the swarm to destroy everything that isn’t itself is to hold the mirror up to humanity and reflect its own intolerance and xenophobia. In the world of the kinden, insects are people too, but sometimes people are insects…

- From a certain point of view (waves hands mysteriously).

- Don’t remember the ant section? Then you probably read the other version. In the original version it wasn’t included, but formed part of another book, the Book of Merlyn which was not published in White’s lifetime – he salvaged the ant section, amongst others, for a revised later printing of Sword in the Stone.

- Or not a cockroach – the original translates, I’m informed, as “vermin”, which actually brings the human alienation point over much more sharply. The description of his physical difficulties certainly shows some sort of beetle or roach, though.

- Metamorphosis as a parallel to the way people are treated when disabled is not something I’ve seen discussed, but surely it must have been.

- Not an arachnophone, as originally typed. Tolkien as The Spider Whisperer is, however, a perversely attractive idea.

- Please consider the tiny, tiny minority of insects that actually live in a caste-structured hive society.

- Also, that’s not how ant nests and the like actually work, of course, but, like I say, convenient shorthand. We look at ants and see ourselves.

- There was a mad moment when the whole series very nearly turned into Redwall with woodlice, with actual insects as the protagonists, but thankfully I came to my senses and wrote something that had at least a tiny chance of anyone wanting to read it.

- And if that’s not one in the eye for the ‘faceless devouring swarm’ I don’t know what is.

Oh my. I love the art in this piece, and I’ve been reading Adrian’s books for a few years now. You all should try them!

The German original has ‘Ungeziefer’ which is a pejorative version of ‘insect’, so vermin sounds about right. Ungeziefer is the sort you use poison spray to get rid of. Small wonder Gregor doesn’t exactly embrace his new form. ;)

@Gabriele — You learn something new every day! Neat tidbit. :)

That’s fascinating @gabriele. I had no idea!

Pretty cool stuff, in no small part because… I don’t think I’ve given enough thought to insects. In a lot of ways, they’re one of the more “alien” species, aren’t they? More incomprehensible than, say, snakes.

There is a genuine tradition, mostly a Central/Eastern European one, of using insects to examine human nature. The Netherlands also has a well-known and popular book, “Eric or the little insect book” by Godfried Bomans, where a little boy gets lost in a painting depicting a summer meadow and meets class-conscious wasps, a philosophical bumblebee, an emotional and poetic butterfly, a self-important burying beetle, and an ant colony which adopts him. A running gag is the protagonist telling the insects how they should be behaving based on his school biology book, with the puzzled insects trying to comply.

[…] it up, so that the result is possibly the nicest thing I've had on a website in a long while. Insects are People Too is my text, and I go into some of the literary antecedents of the insect-kinden, and precisely why […]