I still remember the day I got my first sight of serious mountains. I was a student at Caltech, working at JPL as a summer intern, and one of the engineers on my project invited me along on a backpacking trip in the Sierra Nevada. It’s a good thing I wasn’t the one driving to the trailhead. I probably would’ve crashed the car when we reached the Owens Valley and saw the Sierra’s stunning eastern escarpment. Jagged snowcapped peaks rise to 14,000 feet straight out of the sagebrush and alkali desert of the Owens Valley, which is one of the deepest in the world.

As it was, I craned my neck out the backseat window with my jaw hanging open and only one thought in my head: OH HELL YES. I yearned to climb those airy ridges and balance on those serrated pinnacles. But during my undergrad years I had to settle for occasional backpacking trips in the Sierra. As a student I had no money, no car, and most climbers I knew were rock jocks rather than mountaineers.

If you accidentally kick your gear sling off a ledge, you’d damn well better know how to come home alive without all those fancy bits of metal.

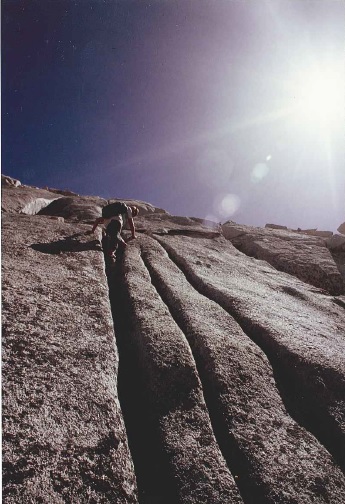

When I moved to Colorado for grad school and at last had some spare cash, the first thing I did was sign up for an 8-week mountaineering course taught by the Colorado Mountain Club. The CMC is a bastion of hard core, old-school mountaineers. In addition to modern techniques for multi-pitch roped climbs and glacier travel, we practiced historical methods like hip belays, pebble chocks, and body-wrap rappels. Our instructor said, “If you accidentally kick your gear sling off a ledge, you’d damn well better know how to come home alive without all those fancy bits of metal.” We climbed technical rock routes in hiking boots rather than specialized rock shoes, so we’d know how to ascend peaks without the advantage of sticky rubber soles. I went on scores of CMC trips and climbed every peak I could manage.

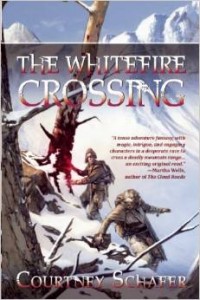

Climbing is a strange, insular, addictive pastime. For many, it’s not a hobby, it’s a lifestyle. Long before I sat down to write my first novel, it had struck me that certain parallels existed between climbing and the way magic and mages are sometimes portrayed in fantasy. So when I did write The Whitefire Crossing, I thought it would be interesting to contrast the viewpoints of two protagonists: one a climber who well knows the lure of dancing with death, the other a mage attempting to reject the deadly style of magic he’s been trained to cast.

More, I knew right away what real-world setting would inspire my story’s landscape. Even after all my years in Colorado, the Sierra Nevada remain the mountains of my heart. It’s not just the stark beauty of the Owens Valley and eastern Sierra that fascinates me, but the region’s wild and woolly history. After all, what brings people other than explorers to areas so remote and arid? One word: profit. In the real world, this meant water – the Owens Valley was the site of the fiercest battles of the California water wars, immortalized in the movie Chinatown. Though the Sierra Nevada are rich in minerals and gems, the logistical difficulties of the Owens Valley terrain made large-scale mining efforts there impractical – most of the gold rush folks went much farther north, where the mountains are gentler.

“Earth Colossus” by Chase Stone

What if a similar landscape existed in a world with magic?

But, I thought, what if a similar landscape existed in a world with magic? Especially if raw magical power welled up along fault patterns, so that a fault-and-graben geological area like the Owens Valley might result in a deep reservoir of magic pooled within the valley confines? A clever, amoral opportunist might then conceive a scheme to reap untold wealth from the mountains: build a city, and send word to every mage he could find saying so long as they helped provide water and didn’t interfere with his mining operations, he’d let them cast whatever spells they wanted, no matter how dark their methods. Kind of like how the mafia turned Las Vegas from a tiny cow town into Sin City and made a zillion dollars in the process.

Better yet, what if the mobsters of Las Vegas were only a single mountain range away from the Mormons who founded Salt Lake City? Both in such remote, resource-poor areas they’ve got to trade with each other to survive? So I took my lawless city of Ninavel, and on the far side of my Whitefire Mountains, I put a country that views mages with deep suspicion and regulates the hell out of what magic they don’t outlaw.

All that makes an interesting stage to play on, but for me, characters are the true heart of a story. While I’ve certainly had fun drawing on my wilderness experiences to tell Dev and Kiran’s story, the climbing and all the worldbuilding are tools to explore issues of trust and partnership, of safety vs. freedom.

But as far as the climbing goes, I don’t like to repeat the same ground. In The Whitefire Crossing and The Tainted City, adventure scenes took place in the mountains. But in the final novel of my trilogy, The Labyrinth of Flame, I’ve switched things up a bit. As a climber, mountains aren’t my only playground. I also love the slickrock desert canyons of Utah, where phantasmal spires loom above slots so narrow and deep the sun never touches their depths.

Utah’s red-rock desert is a land of secrets. Hidden seeps, surprise slots, labyrinths of fins and domes that entice you to explore ever deeper. You can feel the weight of eons in the silence; the desert is ancient in a way that mountains are not. What better setting for a story in which my characters are in a desperate race to uncover truths hidden deep in the past? To add a little spice, canyons have their own specialized set of dangers: flash floods, keeper potholes, hypothermia. (Yep, hypothermia. The air temperature in the open desert above may be 100F, but water lurking deep in slot canyons is often cold enough to send even wetsuit-clad canyoneers into hypothermic shock if they can’t move through the canyon quickly enough.) People think rock climbing is dangerous, but canyoneering takes a far higher toll among its enthusiasts.

Perhaps I should have taken that as a warning! The Labyrinth of Flame has certainly had a bumpier road to publication than its two predecessors. After my publisher Night Shade Books’s near-miss with bankruptcy, I decided to put out the book myself rather than risk further publisher problems preventing the book from reaching reader’s hands. Thankfully, that’s led to a happy ending. My Kickstarter to fund production of the book has exceeded its goal: I’ll be able to publish an edition as professional in quality as the first two books in the series. Maybe even pay for interior art, if the Kickstarter does well enough before the end (which is tomorrow!). Knowing the book will be a reality feels as amazing as my first sight of the Sierra Nevada all those years ago; a milestone I will look back and forever treasure.

Thanks for sharing this Courtney.

And, Aidan, once again, a fabulous job on the art to go with the piece.

You’re welcome, Paul! And I must second your kudos for Aidan’s art choices. I just spent a while browsing artist Phuoc Quan’s site, and WOW. Amazing work!