There was a moment the other day when I saw a famous author on twitter point out to everyone that they were not their characters. “If I was,” they said, “we’d all be in danger.” This was a joke, of course – the suggestion was that since a fair share of their characters were murderers or psychotics, then the author could not be them, as the author is not, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, a murderer or a psychotic.

There was a moment the other day when I saw a famous author on twitter point out to everyone that they were not their characters. “If I was,” they said, “we’d all be in danger.” This was a joke, of course – the suggestion was that since a fair share of their characters were murderers or psychotics, then the author could not be them, as the author is not, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, a murderer or a psychotic.

This joke highlights one of the fun, fuzzy, gray areas in writing relationships – where do characters come from? How do writers make them up? Or do they make them up at all?

Characters aren’t precisely “made up,” I don’t think. When we think of fictional characters, we imagine them as just sort of popping into space – they do not exist, and then the writer thinks of them, and suddenly they’re there. Something from nothing, in essence.

But it’s not from nothing. People think writers work with no raw material at all, but they actually do – they work with themselves.

Imagine a writer as a huge, swirling, dripping ball of knowledge, memory, and experience. The ball is so big it’s impossible to hold in your hands, or even to get your arms around – after all, we’re talking about years and years of conscious and subconscious impressions, connotations, associations, all kinds of messy intangibles. And you can’t funnel that into any one character – the ball is just too big and unwieldy for anyone to make a copy of it.

So what does a writer do? They pull off a chunk, like a piece of clay. Then they take that chunk and massage it, and maybe add more chunks from the main ball if they think it’s necessary, and they sculpt it and shape it and adjust it until it has the semblance of a real person – the sculpted chunk’s got emotions, experience, agency, prejudices, goals, all that kind of fun crap.

And they’re all, more or less, derived from that main ball of knowledge, memory, and experience.

But note that the character is not a real person – it’s just a semblance of a real person, a picture. A writer can’t make a real person, in other words – they can only convey the idea of one. If they do this artfully enough – if they pull enough raw material (and the right kind) from the main source to form a well-rounded, reasonable, informed idea of a person – then what the reader receives on their end is a well-written character.

And my personal definition of a well-written character, just so’s you have it, is a character who is thoroughly, meaningfully connected to the world the story takes place in, who is also invested in the story to a believable degree, and acts in an informed, reasonable manner to affect the events of the story to try and meet their goals.

That’s a pretty antiseptic way of putting it. There’s a lot of richness I’m leaving out, in atmosphere, detail, dialogue, internal monologue, all the fun stuff. But you can see that the character’s emotional connection to the world and its story can only be informed by drawing from the emotional experience of the author.

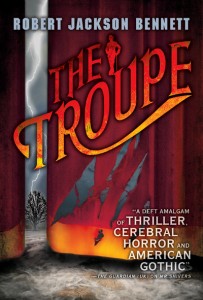

That doesn’t mean that I, having written about starvation, hobos, union busters, and vaudevillians, have any such experience in these matters. I don’t know what it’s like to kill, to break a limb, to jump a train, to brush shoulders with gods, and I don’t really want to know.

But I do know what it’s like to be lonely. I know what it’s like to feel suddenly afraid, like the world is completely barren. I know what it’s like to feel lost in the cacophony of everyday life. I know what it’s like to make crushing choices. I know the voices of cynicism and idealism that argue constantly in my head quite well. These things I know – and they translate to fiction very easily.

I am, in a way, writing what I know.

So no, a writer isn’t their characters. But their characters – especially their memorable, successful, well-written ones – are a part of them. Writers pull a lump off the side of the big, swirling ball inside of them, and maybe that lump just happens to have a streak of flightiness in it, a few pits of bitterness, and maybe a swirl of rage. These are things that are definitely in the author – perhaps constantly, perhaps surfacing only briefly – but they’re there.

So while I wouldn’t expect a writer who writes about murder to have murderous impulses themselves, I bet they think about conflict a lot. I bet they’ve thought long and hard about moral consequences, about the law, about the logistic of it, and how heavy the burden would weigh on their shoulders.

Something can’t come from nothing – everything comes from somewhere. And try as a writer might to write to a reader and an audience, I don’t think any writer can get away from writing to themselves.

[…] A Dribble of Ink (Robert Jackson Bennett) on Characters – Something Never Comes from Nothing. […]

They say when you’re not writing, you should be keenly observing your surroundings and the interactions of the people around you. It’s part of the writing process.

I guess it’s important to always invest some kind of emotion into your writing, to dig into your past and find something that might have made you feel similarly as the character you’re writing about.

Enjoyable, interesting post.

Thanks, Robert.

Indeed, characters must come from characters. I can only imagine the mind of Mark Lawrence, for example, and the place where Jorg Ancrath comes from…

How about the minds of Brett Ellis (American Psycho) or Hubert Selby Jr. (The Room)…