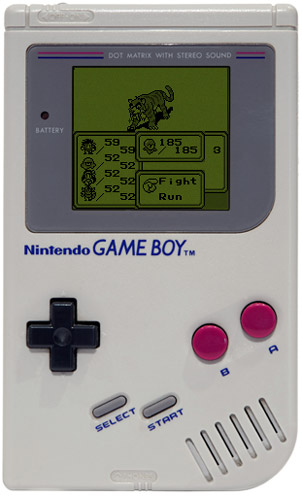

I still remember the first time that I saw a Japanese Roleplaying Game (JRPG). Like many people of my generation, it was a Final Fantasy game, though not one so obvious as Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy VI (or Final Fantasy 3, if you’re familiar with the North American naming scheme), or Final Fantasy VII. No, it was Final Fantasy Legend II in all of its monochromatic glory on the Nintendo Game Boy.

I was at a friend’s house, and his cousin was also visiting. I’d never met the cousin, but he had a Game Boy (like me), so I liked him almost instantly. But, where I was eradicating (or, more accurately, being eradicated by) the Footclan in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or dodging winged-Moai statues in Super Mario Land, he had this slow, boardgame-like game, with numbers, equipment, a map, and so many other elements that I was unfamiliar with. In particular, I remember a fight with a tiger. The one pictured here, in fact. As I think back on it, I can only assume that it’s a low level enemy, fought in one of the early game environments. At the time, however, it was something different. Something frightening.

If you do your homework, however, you’ll quickly discover that my first experience with Final Fantasy was, in fact, not with Final Fantasy at all, but with Akitoshi Kawazu’s infamous SaGa series. See, when Square the developer of the Final Fantasy series, wanted to bring over Kawazu’s zany Makai Toushi SaGa, the first in the SaGa series, to North American shores, they decided that it made more sense to release the title under a respected and successful brand, Final Fantasy, rather than attempting to sell something new. It was the right decision. Final Fantasy Legend II became Square’s first million-selling product.

My parents did the only thing they could: hired a cool, sixteen year-old babysitter. One evening, he brought over a copy of Final Fantasy VI.

At that point most of my roleplaying happened in my head, the sandpile in my backyard, or the forests surrounding my home. I didn’t have even the faintest understanding of numbers-based roleplaying—of dice hit, defense, or THAC0. Swing stick, beat bad guy—those were my rules. The rules of the fantasy worlds I played in bent to will. Final Fantasy Legend 2 wanted me to do math.

So, though my curiosity was piqued momentarily on that day at my friend’s house, I went back to playing character platformers and their instant satisfaction. I returned to adventuring through jungles, battling pirates, and exploring the cold depths of space, all in the safety of my backyard with my friends and brothers.

For a number of years after that, I forgot about Kawazu’s strange game, and the name Final Fantasy faded into a hazy memory. Until one evening…

Like any family of three young boys, my brothers and I were quite a handful. As the oldest, a ripe eleven years old, I led the charge. Vivid memories still fill my head of the time we were climbing up-and-down the ladder-like sides of a bookshelf in my living room, only to bring it crashing down to the floor, barely avoiding being crushed (and further embarrassment for my mother’s friend, who was babysitting.) After that incident, attempting to wrangle up three rambunctious boys, my parents did the only thing they could: hired a sixteen year-old dude with an SNES.

One evening, he brought over a copy of Final Fantasy VI.

Graphics

Creative Limitations

Looking back on development of Final Fantasy VI, co-writer/director Yoshinori Kitase said, “I supposed that action games, for example, relied on sense and instinct while RPGs appealed more to reason and logic.”

Final Fantasy VI was Kitase’s first opportunity to head Square’s mainline franchise, and his enthusiasm shows in all of its loving touches and commitment to the ideals that ensured that the game would not only be successful at the time of its release, but be considered a genre classic in the years to come.

“It’s maybe strange to say [this], but I miss the limitations of making games in those days,” Kitase acknowledged. “The cartridge capacity was so much smaller, of course, and therefore the challenges were that much greater. But nowadays you can do almost anything in a game. It’s a paradox, but this can be more creatively limiting than having hard technical limitations to work within. There is a certain freedom to be found in working within strict boundaries, one clearly evident in Final Fantasy VI.”

Those limitations, and the freedoms that Kitase attrubutes to them, had a profound impact on creating the passion-filled sixth entry in the series, and none moreso than the remarkable fact that development of Final Fantasy VI took only a year. By contrast, development of Final Fantasy XIII took five years. Conceptual design began immediately after the release of Final Fantasy V in December 1992, and production/development of the game occurred during 1993. Final Fantsy VI was released in Japan on April 2nd, 1994, just 16 months after the creators sat down to begin sketching their first ideas on paper.

“It was a hybrid process,” explained Kitase. “[Hironobu] Sakaguchi came up with the story premise, based on a conflict with imperial forces. As the game’s framework was designed to provide leading roles to all the characters in the game, everyone on the team came up with ideas for character episodes.”

It was a truly collaborative effort, as Kitase is quick to point out. “I can’t say that I conceived the complete story,” he told Edge Magazine. “Locke and Terra, for example, are greatly coloured by Sakaguchi’s influence. Meanwhile, the background and in-game episodes for Shadow and Setzer were mainly devised by Tetsuya Nomura, while Kaori Tanaka provided suggestions for Edgar and Sabin, among others. I devoted my time and effort to creating Celes and Gau.”

The Women of FFVI

At that time, JRPGs, at least those that made it to North American shores, lacked the emotional sophistication of even the most rudimentary novels. Even the Final Fantasy series was filled with stock storylines, puddle-deep character relationships, and dialogue that did no favours to anyone. Final Fantasy VI isn’t perfect in this regard, but at the time, Hironobu Sakaguchi and Yoshinori Kitase’s story, along with Ted Woolsey’s (doomed form the get-go, but) competent translation, opened up a grim world full of adult themes and situation, such as genocide, the effects of colonialism, and suicide. On top of this, the Steampunk aesthetic was a kick in the pants for a genre that spent (and still spends) too much time emulating juvenile Dungeons & Dragons campaigns.

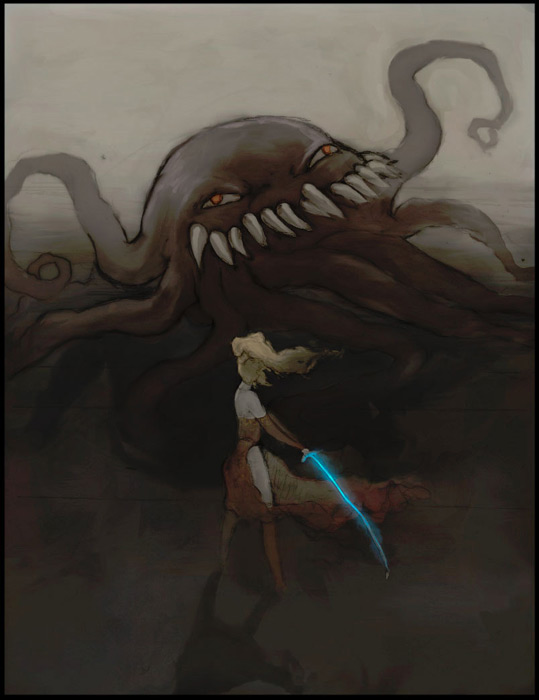

At the emotional core of Final Fantasy VI are two women: Terra Branford and Celes Chere.

Final Fantasy VI was a step ahead of the genre, and, frankly, the popular fantasy genre in its entirety, by framing its narrative around two women. And not just female characters as voiceless avatars for the player, but genuinely powerful and authoritative women around whom the world is shaped. Celes is a high-ranking and powerful general in the Gestahlian Empire, and Terra is the Empire’s greatest weapon. Together, they have the power to reshape the world.

Throughout the game’s narrative, layers are peeled back from each of their respective lives and it becomes evident that in the hands of the Gestahlian Empire, the two women, from two very different origins, suffer under similar threats and expectations from those they have grown up with and lived beside their entire lives. Two powerful women, one naturally gifted with magic, the other imbued with the power through Gestahl’s ghastly exploitation of Esper magic, are both trapped by circumstance and the lies that surround them. This theme of captivity runs in parallel through the storyline of both women, and they each find their own method for coping with the trauma that they have faced, and the conflicts they must overcome.

Art by じゅ

Born to a human mother, Madonna, and an Esper father, Maduin, Terra Branford is both a symbol for the conflict between the two races, and the lynchpin of Emperor Gestahl’s war, and Kefka’s subsequent reign. Snatched from her mother’s arms as a child, and endowed with a gift for magic not seen since the War of the Magi, Terra is raised by Gestahl to serve as an obedient and deadly weapon.

As the Final Fantasy series is wont to do, players are introduced to Terra as a amnesiac protagonist, her memory stolen by the slave crown she wears on her brow. Final Fantasy VI begins with Terra on a mission outside of Narshe, a neutral coal mining community, where, alongside two other imperial soldiers, Biggs and Wedge, she is ordered to find Tritoch, a frozen esper. Gestahl hopes to abuse the power of the espers, and regain a magic that has been missing from the world for a millennium. Against her will, Terra leads an assault on the innocent citizens in Narshe, running them down and killing them for no other reason than that stand between her and the esper. By placing the player in control of Terra as she does these horrible things, Final Fantasy VI immediately engaged with the player’s sense of revulsion and self-preservation. Even as Terra is discovering the truth about herself, about the horrors that she has committed, the player themselves want to be distanced from their own actions early in the game, a parallel of emotions that has helped Terra Branford to become one of the most beloved characters among Final Fantasy fans.

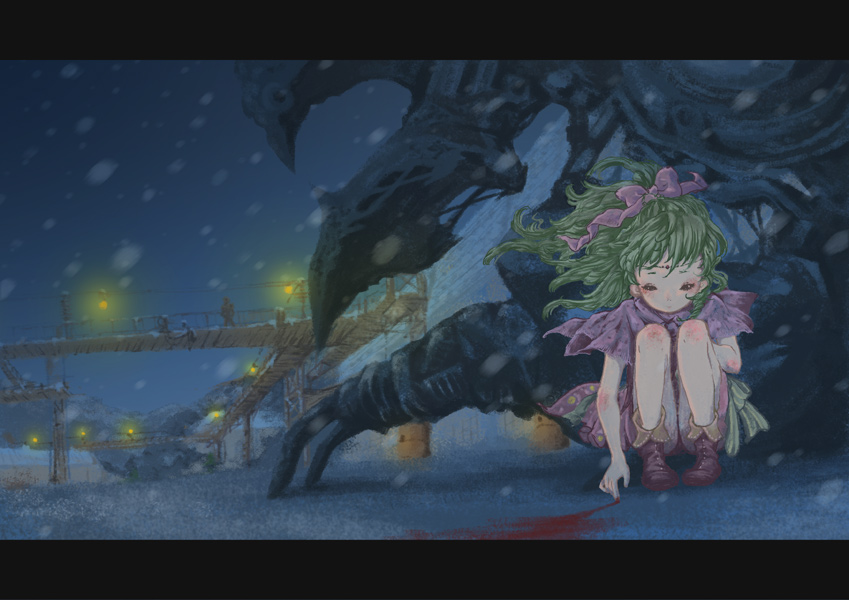

While Terra loses her memory, a mechanism in part to defend herself against the travesties of her past, Celes carries the weight of her actions openly, fresh scars visible to all. Celes must make a conscious decision early in Final Fantasy VI to cast aside her people, the safety of her authority, and join her enemies, a mercenary group called the Returners. Proud and cunning, Celes’s power comes from her ability to adapt, to funnel her passion and belief into a perseverance that symbolizes the Returners’ ideals.

Celes’s strength is challenged in one of the 16-bit era’s most surprising and emotionally nuanced moments: her suicide. Midway through Final Fantasy VI, Celes becomes stranded on a small island with Cid, another member of the Gestahlian Empire, and one of the few to show kindness to the espers. The world around them is dying, the result of Kefka’s actions when he usurped power from Emperor Gestahl and threw the World of Balance into ruin. Cid falls ill, and it is up to Celes (and, by proxy, the player) to keep him alive. While it’s possible to keep Cid alive by feeding him only healthy fish, with no instructions (or GameFAQs), it was almost impossible for gamers to know this on their first play through of the game. When Cid passes away from his illness, Celes, overcome with grief, throws herself from the island’s highest peak.

She wakes, miraculously alive, and, as if a message from god, finds a wounded bird wrapped in a bandana much like one that belonged to her lover, Locke. With it, she again finds her strength, and the will to push forward and reunite with her friends. Without her perseverance, there’s little doubt that Kefka would stand unopposed on his throne atop the world.

God of Power

World in Ruins

At a point in the game when most JRPGs have the player traipsing through caves, Final Fantasy VI pits them against the apocalypse.

Think about that for a moment. The world is destroyed. At a point in the game when most JRPGs have the player traipsing through caves, sneaking into castles, and fighting rats, Final Fantasy VI pits them against a remorseless enemy who succeeds in bring about the apocalypse. It’s not pre-apocalyptic, or post-apocalyptic, it’s the end of the world in real time. So much of the early game is spent building belief in the vision of the Returners, a vigilante group that is set on bringing down Gestahl’s empire, that the pain and disbelief is palpable when Kefka, not Gestahl, is revealed to be the true antagonist.

At the time of Final Fantasy VI‘s release, few games had the courage and foresight to so dramatically subvert players’ expectations. We’re a merry gang of heroes, right? Sure, things will go wrong, but we’re out to save the day, to stop the bad guys. Nope. Full stop. You’re wrong. A year passes in the game, then, after the Floating Continent has crashed into the sea, the World of Balance has been upset by ruin, you’re back at square one: a single character, no party, no airship.

Every legendary story has the single moment when the reader/viewer/player realizes that they’re participating in something special, something beyond the bounds of the average. From George R.R. Martin’s Red Wedding, to Frodo’s claiming of the Ring, to Rosebud, that moment transcends the medium and cements itself in the participant’s memory, never to be forgotten, with a feeling never to be recaptured. Kefka’s triumph is the moment when Final Fantasy VI goes from being an interesting, progressive mid-90s JRPG, to one of the most iconic and important videogames of the decade. Since then, videogames have grown up, and shocking twists aren’t quite so unexpected anymore, but at the time, the courage of Sakaguchi and Kitase was unprecedented.

The Music

A Cast of Thousands

Beyond the three standouts, Final Fantasy VI offered a diverse and interesting cast of characters, both playable and not playable. Ask any player who their favourite character was, or which four comprised the perfect party (Locke, Celes, Terra, Edgar, thank you very much), and you’ll get a different answer every time. While future RPGs, such as the Suikoden series, would usurp Final Fantasy VI‘s throne in terms of playable party members (Suikoden features 101 recruitable characters), there’s a balance to Final Fantasy VI‘s party that ensures each playthrough is unique. No character is wasted, everyone has the potential to be a valuable party member.

Coming off of Final Fantasy V, which featured a robust and a nearly unrivalled job system, which allowed the player to customize their party of four in hundreds of unique combinations, Final Fantasy VI reduced the system complexity by creating the esper system, which allowed characters to equip magical shards that taught them magic spells and provided a unique bonuse to certain statistics when they levelled up. In addition to the esper system, each playable character had their own special ability: Sabin’s Blitz mimicked the martial arts and complex button sequences of arcade fighters, Cyan’s Bushido rewarded player patience, Celes’ Runic put players one step ahead of their opponent’s magic spells, and Gau’s Rage could mimic the attack of nearly any enemy in the game.

All of a sudden, players were able to form a party that was unique to their play-style, but also ensured that every character was powerful across the board. Sabin, for instance, is a martial arts master, and has a bodybuilder’s physique, but intrepid and creative players discovered that he made a great healing and support mage, thanks to his high speed and resiliency. The freedom afforded by this enormous cast of interesting characters ensured that there was a little bit of something for everyone. Trading stories on the playground, every kid had a different argument about how their unique mix of characters was the one to beat.

In addition to their unique abilities in battle, all of the fourteen playable characters, along with many of the non-playable characters, had rich backstories and side-quests that encouraged players to dig into their history and discover more about the various interlinking relationships that brought everyone to the Returners’ cause.

“The idea was to transform the Final Fantasy characters of the time from mere ciphers for fighting into true characters with substance and backstories who could evoke more interesting or complex feelings in the player,” said Kitase. “Since the scale of each character’s individual story was expanding, I began linking this to the concept of different dramas developing, according to the player’s choice of character in the game.”

“Maintaining a careful equilibrium between all the characters was probably the greatest challenge I faced,” he continued. “However, I ended up so involved with each personality while scripting the scenarios that there were points where, looking back at the game today, it’s clear that I somewhat lost this balance. For example, as the scenes featuring Celes and Kefka progress, these characters (while not directly playable in the game) became far greater and more influential than originally intended when development began.”

Like any great story, Final Fantasy VI grew in its telling, and Kitase was unable to ignore the gravitas of the game’s greatest characters.

Full Bloom

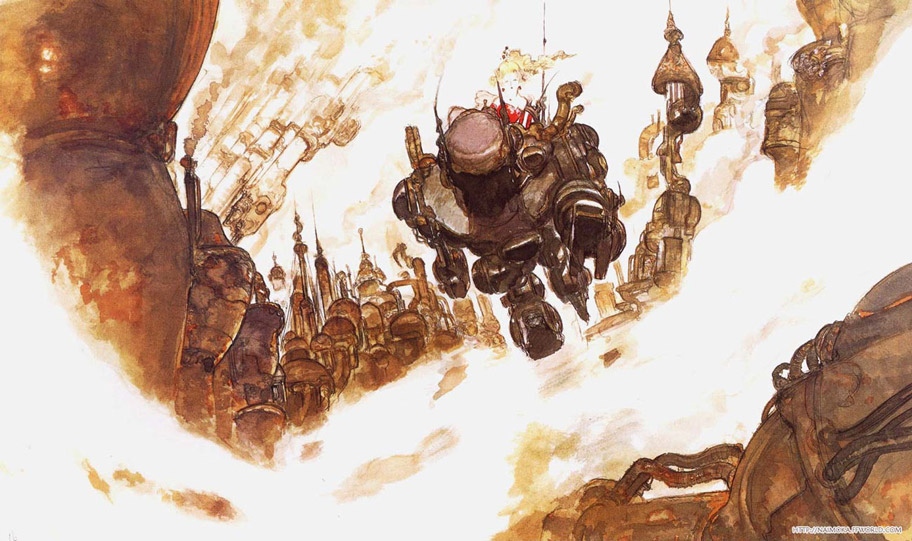

Final Fantasy VII, released three years after Final Fantasy VI changed the landscape of gaming. Like an earthquake of unimaginable magnitude, Cloud Strife and his misfit band of revolutionaries took the groundwork laid by its predecessors and, through sheer cinematic indulgence and grandiosity, opened the world of JRPGs to the masses.

Final Fantasy VI established a lot of the new traditions that would define the Final Fantasy series through the late ’90s and into the early ’00s, including darker narratives, morally ambiguous characters, sci-fi/steampunk aesthetics, and, perhaps most importantly, the first signs of the cinematic storytelling methods that would help Final Fantasy VII turn the industry on its head in 1997.

One has to look only so far as the Opera Scene, famous among gamers and Final Fantasy fans for its iconic music and unique place in the series’ history, to see the first signs of this change. All of the Final Fantasy instalments before Final Fantasy VI were full of dramatic plot points: heroic sacrifices, personal triumphs, feats of strength and perseverance. In so many ways, those narratives were the perfect culmination of imaginary childhood adventures. Elves and dwarves, evil to banish, and squeaky-clean kingdoms to save. Final Fantasy VI was dirty and unpredictable, and the Opera Scene asked players to take a step back, and recognize that even during those dire times, there was some hope, some beauty still left in the crumbling world. The Opera Scene wasn’t powerful for its bravado, but for its delicacy and tenderness. For a generation of gamers accustomed to blasting away enemies with their BFG 9000s, Final Fantasy VI captured minds and hearts with a Disney-esque musical interlude.

Such storytelling techniques were abused to great effect in the following entries in the franchise — big, dramatic CGI cutscenes interrupting gameplay with (at the time) mind-blowing action scenes that helped pull the gamer into the game world in a way that static text and small, barely animated sprites never could. There’s a scene in Final Fantasy VII that features Cloud, the spiky-haired protagonist, riding a motor cycle down a set of a stairs. I remember exclaiming to my friend that that was the pinnacle of videogames, graphics could get no better. (I was 14 years old, it was cool, okay?) But, hindsight being 20/20, I now look back on that scene and laugh, realizing that Square was never able to recapture the naive creativity that led to the Opera Scene.

Art by Carlos F. Villa

Final Fantasy VI set the groundwork for the cinematic future of Final Fantasy games, but later entries in the series, especially the most recent, like the lamentable Final Fantasy XIII, seem to have forgotten so much of what made the final 16-bit entry so timeless. Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII continued with the tradition of establishing an interesting world where fantasy clashes with modern technology, but they both faced issues that seemed to grow out of Square’s inability to balance ambition with solid game design and storytelling. Final Fantasy VII was bogged down by a near incomprehensible translation, and graphics that lacked the innate charm of its predecessor. Final Fantasy VIII featured contemptible characters, and introduced players to the Draw system, which relied on too much repetitive grinding and lacked the simple elegance of the Esper and Materia systems before it. Even Final Fantasy IX, a personal favourite, and clear homage to Final Fantasy games of past, tossed away the blazing-fast battle system from Final Fantasy VI for a slower experience, and forced players through most of the game with a set group of characters, each strictly adhering to a particular class archetype.

The Final Fantasy series is rightfully lauded for its courage to experiment and evolve its formula from entry-to-entry. However, this innovation must be practiced carefully, as too much experiment, not properly weighed against fan expectations, have been damaging to the series. At their core, each game in the series features familiar concepts, such as world elements (moogles, cactuars, summonable eidolons/espers), characters (most notably, Cid), themes (magic vs. science, imperialism, human purity), and naming conventions (for magic spells, abilities, etc.). These elements, along with the series’ recognizable visual identity, help gamers, both committed and casual fans, identify the series and feel comfortable with each new entry. Striking this balance between established traditions and trailblazing concepts helped to keep the series fresh for nearly two decades. However, in recent years, with the release of both Final Fantasy XIII and Final Fantasy XIV, there is worry among critics and fans that Square Enix has forgotten or lost the ability to understand what made their earlier games so successful and enduring.

Art by Mikaël Aguirre

“What made the Final Fantasy series so innovative was the emotion realised from drama within the game in addition to those other elements,” said Kitase.

In the two decades since its release, Final Fantasy VI has remained one of the most beloved and universally praised videogames among fans of all ages. For those who discovered it upon its release, it is a nostalgic reminder of a time when passion filled the industry, and the JRPG genre was still ripe with potential and full of brave new adventures and ideas (and not yet weighed down by corporate expectation and pressure). For those who discovered it through re-releases, from the PlayStation, to the Gameboy Advance or, *shudder*, the iOS and Android versions, it has become a beacon of the heights that videogames can reach when they push through hardware limitations, and fuel development with thoughtful innovation.

“What made the Final Fantasy series so innovative was the emotion realized from drama within the game in addition to those other elements,” said Kitase, thinking back on the early days of the series. “I believe this innovation was more apparent than ever before in the sixth game. This game really brought that creative goal into full bloom.”

For twenty years, we’ve plumbed its depth, and for twenty years the hard-fought adventure of Terra, Celes, and Locke, and the terrifying behaviour Kefka has won our hearts and proven that some things only grow finer with age.

Now I want to have an old-school RPG fest!

I came to the RPG game later than most, when my parents gifted me with a Playstation and a copy of FFVII, with no memory card, and with me having had zero interest in RPGs or video games more complex than Solic the Hedgehog. Whether it was parental prescience or just the dumb luck than can sometimes follow a bad gift decision, I ended up playing it, then liking it, then getting hooked on RPGs. I found older games in the series. Found older games from different series. Found friends who also played them. And holy crap, they were GOOD!

I remember playing FFVII in high school, seeing how far I could get in the game sans memcard, leaving the system to run overnight for a few hours while I slept and then started playing again in the morning. I inevitably died at the same place each time, outside Wutai after Yuffie stole all my materia (I didn’t realise at the time that I could skip that subquest entirely…) Glorious memories of years gone by, I tell you!

FFVI isn’t one of my favourite games in the series but it does rank pretty high up there, making me a bit of an oddball in a crowd of my friends who seem to prefer FFIV to just about any other game in the series.The magic system, the characters, the graphics, the setting. Exploiting crazy glitches just to see what would happen.

Yeah, now I DEFINITELY want to have an old-school RPG fest!

>>Fun Fact: Scott Lynch named Locke Lamora after Final Fantasy VI‘s ubiquitous treasure hunter: Locke Cole.

Now *that* I did NOT know. Interesting!

Final Fantasy was never my cup of CRPG, alas, or maybe I would have twigged to it. I played CRPGS in the early days (Ultima IV, the D&D gold box games, etc) but for a good long time, the only computer games I played were strategy. Bioware has changed that to an extent, though, with Dragon Age.

This TheVerge-style of post, with large images, pull quotes and sidebars (and even audio), is really cool and well done, Aidan.

Thanks, WHM. The Verge and Polygon were my inspiration for assembling this article, so I appreciate the comparison!

[…] “Life… Dreams… Hope… Where do they come from?” A Final Fantasy VI Retr… […]

[…] two friends will not have the same cherished memories. From the Opera House to the Final Battle thegame continues to be analyzed. Its large and complex cast of characters explored as they faced the living god Kefka, the […]

after read your article, I want to play final fantasy VI.

Perfect description of the best Final Fantasy, this game is a work of art where even the bad points are good things.