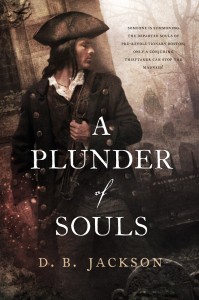

Tomorrow marks the release of A Plunder of Souls, the third instalment in my historical urban fantasy, the Thieftaker Chronicles. For those who are unfamiliar with the series, the books are set in pre-Revolutionary Boston, and feature a conjuring thieftaker (sort of an eighteenth century private investigator) named Ethan Kaille.

I have a Ph.D. in U.S. History and so I take my historical research seriously; I’ve done my best to portray accurately the real-life events from the 1760s that coincide with my fictional narratives. I have taken care in my portrayal of historical figures, and I have made every effort to create a Boston that is true to its purported time while also being accessible to twenty-first century readers.

That last phrase, though — “accessible to twenty-first century readers” — is where all of this gets a little tricky.

That last phrase, though — “accessible to twenty-first century readers” — is where all of this gets a little tricky. What exactly does that mean? In some respects, it’s merely a stylistic decision that I have to make in my writing. My point of view character is a man of the eighteenth century, as are all of the people with whom he interacts. I could have Ethan and my other characters talk and think in precisely the vernacular used in the 1700s — that would be the historically accurate thing to do. But doing so would render my books all but incomprehensible to today’s readers. This was a period during which word meanings and rules of common syntax bore little resemblance to our own, and when even spelling was different from what we’re used to today. (For example, “s” was often written as “f.”) Historical authenticity is fine, but I want people to read my work; it’s hard for me to make a living if they can’t.

My approach to dealing with this has been to write the books in a way that nods toward the historical period without going overboard. Or, put another way . . . My solution has been to compose the books in a manner that harkens to the period in question, without producing a result so at odds with the customs of our own time that it becomes indecipherable. (See what I did there?)

In other respects, though, that social and temporal gulf between my subject matter and my audience creates more difficult issues. Boston in the 1760s was a fairly homogenous city, and the North American colonies in the mid-to-late eighteenth century were not exactly notable for offering scads of professional advancement opportunities to women. It would have been easy — and again, historically faithful — for me to populate the Thieftaker books with nothing but white male characters, making just a few exceptions, perhaps for Ethan’s love interest, a few female crime victims, and some serving girls in Boston’s taverns. Everyone who reads the books will notice immediately that I didn’t do this.

Ethan’s nemesis in the Thieftaker books is Sephira Pryce, a rival thieftaker who is brilliant, cunning, ruthless, corrupt, skilled with a blade and with her fists, fearless, and strikingly beautiful. She is modelled after a historical figure, a thieftaker named Jonathan Wild, who worked in London in the early 1700s. He, too, was brilliant and ruthless and corrupt, and I wanted to have a Wild-like character who would work at cross-purposes with my honest but down-on-his-luck hero. I chose, though, to make this nemesis a woman because I thought that doing so would add a bit of sexual tension to their rivalry, making their interactions that much more compelling and fun for my reader. I will admit though that I also did this because I didn’t want my books to be top-heavy with male characters.

There can be no mistaking the fact that she is a person of color in a book — and in a city — that has few others. There were, in fact, free people of African descent in Boston in the 1760s, and there were many women who owned taverns.

In addition to Sephira, Ethan also interacts with a woman named Janna Windcatcher, a conjurer who hails from the West Indies, and who owns a tavern on the Boston Neck. Janna is irascible and a fun character to write. She is also the most knowledgable and accomplished conjurer Ethan knows, and he often goes to her for help when working on a difficult investigation. But there can be no mistaking the fact that she is a person of color in a book — and in a city — that has few others. There were, in fact, free people of African descent in Boston in the 1760s, and there were many women who owned taverns, although most were widows who inherited their establishments from their deceased husbands. But Janna is another character who could just as easily have been male and white. I chose to make her otherwise.

The other prominent female character in the series is Ethan’s love interest, Kannice Lester, who is also a tavern owner who came to own her establishment as so many female innkeepers did. Her husband died in the 1761 smallpox epidemic. Of the three female characters I’ve mentioned in this post, Kannice is probably the one who conforms most closely to historical realities (Sephira is the one who conforms the least). Still, she is strong-willed, independent, and someone who challenges Ethan often, despite being in love with him.

Why did I choose to create characters who are, in certain key ways, at odds with the historical norm for the period in which I’m writing? That’s a more complicated and difficult question than it might seem. I can see where some might accuse me of bending to the pressures of “political correctness.” Diversity, multi-culturalism, inclusiveness — call it what you will — I suppose one could make the case that I was striving for it in a way that compromises the historical realism of my books. Others might say that I was catering to the marketplace. Women read in far greater numbers than do men. By surrounding my male protagonist with strong, engaging, and entertaining female characters, I’ve probably helped my sales.

The truth is I did it for both of those reasons. I did think that the book would be more marketable if it had strong female characters. And I also wanted to write a book with a more diverse cast than a strict adherence to historical realities might have allowed. It wasn’t necessarily that I was trying to be PC, but I did want to write about different sorts of characters. Ultimately, I chose to include these particular characters in the hope that doing so would make the books more fun for my readers as well as for me. But I’m not going to deny that I made a “modern” choice, perhaps even a somewhat anachronistic choice.

In the end, I was writing a piece of fiction, one that reflects my values and those of the culture in which I live every bit as much as it does those of my lead character and the society in which I placed him. I expect some will say that’s a flaw in the books, and in me as a writer. I’m willing to accept that. Because to my mind, making my characters relatable for a twenty-first century audience is not all that different from making my prose and dialog more understandable for those same readers. I’m not trying to create a historical document. I’m writing a novel. Do I want the historical elements to be accurate? Sure. And to the extent that my narrative and characters and magic system allow this, I believe they are. But I’ve inserted thieftakers into pre-Revolutionary Boston, even though they were not actually active in the colonies in the 1760s. I’ve also inserted conjurers, fictional murders, ghosts, and a host of other story elements that have no place in a “realistic” portrayal of Colonial Boston. In that context, giving a somewhat broader role to female characters and characters of color seems like a pretty modest stretch of the imagination. More, I believe that those characters bring personality, originality, and even a bit of charisma to the Thieftaker books and stories, more than making up for any loss in historical verisimilitude that they might have cost me. And that’s a trade this author will make any day of the week.

Sephira is one of, to my mind, the “breakout” elements of the series. Villains/antagonists that are well defined and have goals, plans, motivations and drives of their own make a series golden. The way you weaved her into the background elements you’ve taken and used is well done, David.

Er, no. That “s” that looks like an “f” was NOT pronounced like an “f.” It was pronounced like an “s.” See http://typefoundry.blogspot.com/2008/01/long-s.html. Also, I don’t think it’s necessarily a-historical to have strong female characters who do work normally associated with males. As a historian, you should know that records are incomplete and often biased. Or to put it another way: How much more improbable is the female nemesis than the male hero? They’re both way outside what would have been “normal” for that period (and I’m not even referring to the fantasy elements).

Many thanks, Paul. Kind of you to say. As you might imagine, it was a labor of love. She is one of my favorite characters from any book I’ve ever written. So much fun to write. She’s like Jessica Rabbit — she’s not really bad, she’s just drawn that way. . .

[…] need to write books that resonate with a twenty-first century audience. It’s called “Hey! You Got Your 21st Century in My Historical Authenticity,” and I hope you enjoy […]

The covers for these books are beautiful!

@Jordan — Covers courtesy of Chris McGrath!

Rudy, thanks for the correction on the s=f. My mistake. On the other hand, I do think that Sephira’s character is a good deal further from what would have been thought of as “normal” in a gender sense than Ethan’s character. Historical biases aside, and taking into account the fact that gender roles in the 18th century were not as fixed and limiting as they would become in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the fact remains that Sephira is just more of a stretch from a realism perspective. But I’m grateful to you for your comments, and again thanks for the corrective to my mifftatement. :)

Jordan, yes, those covers are great, aren’t they. And thanks, Aidan for the shout-out to Chris.

“Women read in far greater numbers than do men. By surrounding my male protagonist with strong, engaging, and entertaining female characters, I’ve probably helped my sales.” This is faulty logic–the assumption that female readers are only interested in female characters, or at least more interested in female characters. Catering to female readers doesn’t just mean adding more female characters, however strong they are.

Otherwise, though, great article.

Per Rudy’s comment, and David’s wishes, I’ve updated the article to more accurately reflect the language discussed above.

Thanks for the comment, Amanda. I never said that female readers are ONLY interested in female characters. What I was trying to get across was this: Being completely true to historical concerns, I could well have written a realistic story with nothing but male characters in the most prominent roles. And that, I believe could have hurt my sales. It also wouldn’t have been the book I wanted to write, since I happen to like strong characters of both genders. And, I would add just anecdotally, I was at a con two weekends ago and a woman picked up my book while I was standing in front of a bookseller’s booth, looked at the cover, and said, “Male protagonist. I’m not interested,” and put it back down. Seriously. Now, I’m not saying that she’s representative of all female readers, but I do believe she is representative of at least some. Just as there are some guys who won’t read certain fantasy or SF novels because they have women on the covers.

I agree that “catering to female readers” doesn’t just mean adding more female characters — again, I never said that it did. But again, there is some truth to the counter-argument: If I had written the book with no female characters of note, it might have alienated female readers, and with good reason.

Anyway, glad you liked the rest of the piece.

Thanks for the putting in the change, Aidan.

[…] Jackson, author of the Thieftaker Chronicles, wrote an insightful article for A Dribble of Ink on his own approach to historical accuracy in his work. Jackson holds a Ph.D in American History. His most recent novel is A Plunder of Souls, the […]

I know I’m a bit late to the party, here, but I wanted to make two comments nonetheless:

Firstly, great article, and great books. I’ve only read the first book, but I really appreciated the fact that the characters, be they male or female, had actual motivations, were fallible, and all those other things known as ‘depth’. I think trying to insert a certain amount of historical accuracy adds to that depth, or rather, adds to the complexity of the context, or ‘world-building’. Using as much of the real world as possible evokes a sense of space and history that I’m not sure you can get otherwise (unless, of course, one is JRR Tolkien).

Second comment: I’m noticing that each female character is described as ‘could just as well have been male’. While I find this infinitely preferable to no female characters at all, one of the things I really miss in fantasy fiction (or fiction in general, perhaps), is female characters who could not just as well have been male. It seems to me that by that omission, writership and readership are buying into the idea that all female lives are inherently boring and meaningless, and the only way to make them palatable to readers is to write ‘male’ stories and clothe them in female bodies. (Yes, this is an exaggeration for effect :-) ) I’ve found in my own studies of history that women did a lot of interesting things and had dramatic lives that would suit themselves to inspiring fantasy, though granted, they usually did not involve battles, weapons, etc – though there are plenty of historical law-suits, i.e. plenty of potentially dramatic conflicts. To get back off my soapbox, though, it would make me really happy to see some ‘realistic’ female characters taken seriously…

That said, I hope, Mr. Jackson, that you keep writing in this series/ this period for a while to come…