Writers often draw upon history, be it for inspiration, for setting, for character, for plot ideas, or for some combination of these. Recently, I have embarked on a new phase in my career, turning from epic fantasy to what I call historical urban fantasy. And even as I borrow so many of my ideas from the past, I find myself wondering what I owe history in return.

Writers often draw upon history, be it for inspiration, for setting, for character, for plot ideas, or for some combination of these. Recently, I have embarked on a new phase in my career, turning from epic fantasy to what I call historical urban fantasy. And even as I borrow so many of my ideas from the past, I find myself wondering what I owe history in return.

I have a Ph.D. in U.S. history, and though I have been a refugee from academia for far longer than I was actually a part of it, I still harbor a certain reverence for the study of our past, and a near-obsessive concern for historical accuracy. I also understand that “accuracy” is a term that is both freighted with unintended meanings and nearly impossible to define for more than one person at any given moment. Still, to the extent possible, I want to get the easily-verified stuff right. I want to put the correct people in the correct place at the correct time.

The first thing I owe to history: attention to detail. This is not to say that I can’t bend some “facts” to my own purposes.

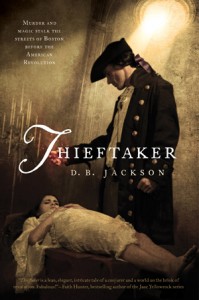

That I believe, is the first thing I owe to history: attention to detail. This is not to say that I can’t bend some “facts” to my own purposes. Authors do that all the time. Indeed, often that is the point of our work, whether it’s giving the Confederacy superior weaponry — as Harry Turtledove famously did in The Guns of the South — or having Charles Lindbergh, an anti-Semite and white supremacist, defeat Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940 Presidential election — as Philip Roth did in The Plot Against America. In my new book, Thieftaker, I portray Boston in 1765 as accurately as possible, with two notable exceptions: First, in my book the city’s population includes some people who are conjurers, and second, the city has at least two thieftakers working within its boundaries. I’ll leave a discussion of magic and conjuring for another day, but I will readily admit that thieftakers did not actually appear in any North American city until the early 19th century and then only for a very brief period.

Boston, c. 1768

So, one may ask, if we can add thieftakers and conjurers to a city population, or give modern machine guns to the army of the Confederacy, or change the outcome of a Presidential election that occurred over seventy years ago, all in the interests of satisfying our narrative needs, how could it possibly matter what color Samuel Adams’ house was painted? And while I know it’s not a satisfactory answer to the question, I will start by saying “Because it just does.” Read More »

Hot off of yesterday’s

Hot off of yesterday’s