My parents taught me not to stare.

As children, even as adults, prolonged staring at others is something we do when we first encounter difference. It’s a long, often critical or fascinated look at something to try and understand it, to gauge where it fits in our taxonomy of things. First: is this a threat? Should I respond with a fight…or flight? Second: where does this person fit within my existing boxes? Woman or man? Black or white? Friend or foe?

We have nice neat boxes for everything, boxes we learned in childhood which have been reinforced by stories, by media, by our peers, as we grow older. We stare longest when we cannot fit what we see into an existing box; when we cannot figure out if it’s dangerous, or merely different: which many of us, unfortunately, still feel are the same thing.

And, if after staring long enough, we decide that this different thing is dangerous: we kill it.

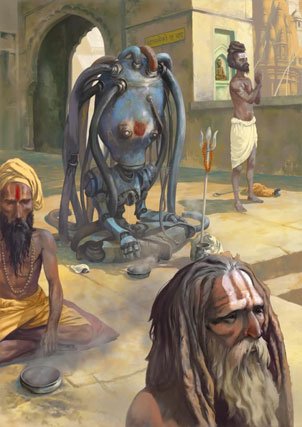

Art by James Eugene

I grew up in a town that was about 98% white. I would learn, decades later, that it was purposely constructed that way, as were many places in the U.S., including the western U.S. where I grew up (California went so far as to ban the immigration of free and enslaved blacks into the state, though that did not prevent those already there from continuing to eke out a living. Also see: the exclusion laws of Oregon).

When I was three or four years old, my family took me to Reno, Nevada. We stayed at the Circus-Circus hotel, and while my dad went downstairs to play cards, my mom ordered up a special treat: cheesecake, delivered in a way totally new to me – via room service.

The knock came on our door. My mom opened it. And there was a very dark man in a very white coat holding a silver-colored tray.

“Mom!” I said, three or four years old and having never seen anyone much browner than a pale person with a suntan. “Why is that man so black?”

My mom, mortified, laughed and hushed me and tipped generously, I learned later. These were not polite questions. They revealed where and how I’d grown up. The question revealed the constructed lie of how we lived.

When he was gone, she told me, simply, that some people were born with different colors of skin, like different colors of hair. Being three or four years old, I was perfectly contented with this answer, and went on to happily eat my cheesecake. It would be four or five years more before I realized that in our society, skin color was not seen in the same way hair color was, even if, in my kid’s view of the world, it made exactly the same amount of difference as blue eyes or brown, red hair or black.

Even a child cannot escape history. We can’t escape what came before us.

Looking back, the irony is not lost on me, of course: the irony that the first person of color I ever saw, as a white child, was a black man serving me cheesecake on a polished platter.

Statue by Ferri Farahmandi

Difference has been managed in a variety of ways, across times and cultures. Because difference is, of course, in the eye of the beholder. The Twilight Zone episode of the same name posits a world where beauty itself is interrogated as a construct. A female patient spends nearly the entire episode covered in bandages while her doctors converse with her, always with their own faces out of sight, in shadow. In the end, it’s revealed that the woman has a movie-star beauty of a face: pale skin, pale hair, sparkling eyes, pleasingly symmetric features.

Hollywood beauty. The beauty of our American culture, collectively, is told to strive for – even if it is so far beyond and outside what any of us actually look like.

Her doctors, nurses, the “normal” people in her world, are revealed to have the melted-looking faces of deformed pigs. They are the beautiful ones. She is the anomaly.

She is the difference.

In the end, she is shuttled off to a concentration camp. A ghetto created for people of her “kind.” They say she will be happier there, among those like her. Most importantly, though: she will be hidden from the eyes of those unlike her. They will be free from seeing her ugliness.

Her difference makes them uncomfortable, and for that grave crime, she must be locked away.

Sometimes difference from a culturally-defined norm has been celebrated – a mark of the gods, divine. Sometimes feared – a mark of evil. But most often, in the culture we call American, what we’ve done the last couple hundred years is lock up and shutter away and refuse to showcase all but the very narrow subset of humanity those in power would like us to believe are the true normal. This dangerous lie has led to the dehumanization of millions; and people who are dehumanized are not simply written out of the cultural narrative. They are, very often, utterly and literally removed from the face of the earth.

I have written before about how our broken sense of what is “normal” feeds into dangerous narratives, and how it limits the lives of women.

These stories – that there is this very narrow subset of “normal” people – upper middle class, white, women being women, men being men – serves to make the rest…not.

But the reality is, this system of stories goes far beyond rewriting history to limit how we believe women fought, or lived. These stories – that there is this very narrow subset of “normal” people – upper middle class, white, women being women, men being men – serves to make the rest…not. Anyone who doesn’t fit is, of necessity, abnormal.

Abnormal often meaning not human.

And not human… well, we know what we do to things that aren’t human, don’t we?

The fastest way to dehumanize a person, or subset of people, is to make them invisible. To lock them away. To say, “This is the stuff of circuses and mistakes. This is the stuff of nightmares.”

It’s easier to reject,fear and destroy what we don’t understand.

It’s impossible to understand what we’re never allowed to see.

Even if, in many cases, what we never see is ourselves.

Art by Tomas Honz

There was an uncomfortable moment of silence from the father, and when he responded, I could hear the tension in his voice. “I don’t know,” he said.

I passed a man and his son headed to a football game the other day. The news is, at present, all about the protest and unrest in the city of Ferguson, Missouri, where peaceful protests in reaction to the shooting of an unarmed teenager were met with an increasingly violent police response.

One would think there would be a profound backlash against this militarized police response, no matter the race of the victim.

The boy and his father crossing the street to the stadium now were white; the boy was about eight or nine years old, and he asked, “Dad, what if it had been a black cop shooting a black kid? What about a white cop shooting a white kid? Why are people upset because it was a white cop shooting a black kid? Would it be different another way?”

There was an uncomfortable moment of silence from the father, and when he responded, I could hear the tension in his voice. “I don’t know,” he said.

I don’t know.

These two people, likely growing up in neighborhoods as artificially constructed as the one I lived in, had no reason to know. They had not spent their lives terrorized by police. Had not had loved ones shot in the street outside their homes. Had not grown up in neighborhoods where simply looking the way they did meant they were quite likely to spend a great deal of their time in prison. The statistics, for these two people – a white boy, a white man, were very different than for others.

Of course they don’t know.

People in power don’t want them to know. They want these people’s allegiance against the Other.

Divide and conquer is a time tested strategy. Divide and conquer works.

How do you explain four hundred years of prejudice, oppression, exclusion laws, terror, to an eight year old middle class white boy on the way to a football game?

The truth is, he will likely never see it. Never even notice it.

And that’s the fault of mainstream stories. It’s the fault of our laws. It’s the fault of the culture we call “ours” but isn’t really representative at all. It is the culture of a select few, assumed to be the culture of many.

But “us” is the fiction. “Ours” is the lie.

Who is “us”?

Art by Brenoch Adams

My academic advisor in graduate school was born with phocomelia. We went into town one day to print and bind copies of my hundred-and-some-odd-page thesis, and she popped into a fabric shop to run an errand before we went to the printer.

I remember seeing a young child at the counter, standing next to his mother, staring at my advisor. Big eyes. Staring. Forever and ever. No break. Goggle-eyed.

I remember being irrationally angry at this child for staring, and I stepped between him and my advisor to shield his view.

Now, I couldn’t tell you why I did it. She had to deal with these stares every day, and worse. It was me who was angry. It was me who was uncomfortable. It was me frustrated with how we notice and process difference.

My mother always told me not to stare. It was rude. It said, “You are different.” And difference, acknowledging difference, was bad. To acknowledge difference was to acknowledge everything that was broken. Yet…how was pretending not to see someone any better?

I feared that stare. Even from a child who knew nothing of its historical implications.

In truth, what was being protected by not seeing was my naïve 4-year-old question that revealed how I was raised, “Why is that man so black?” Staring said we were rural simpletons with a limited view of the world. It wasn’t the difference itself that was terrible to acknowledge, for my parents, I think: it was acknowledging the fact of our own ignorance.

But the gaze, the stare, as many women know, can also be seen as a prelude to an assault. We fear and sometimes covet what we see. And what we fear and covet, often, we will violently assault.

I feared that stare. Even from a child who knew nothing of its historical implications.

I saw myself in his stare.

And that made me angry.

So what is it that we don’t see? That we have stopped seeing? That we don’t want to see?

What we don’t see has a great deal to do with who we are, how we grew up. It has to do with how our society manages the ebb and flow of people; what it considers different, undesirable.

Whether we believe we’re living in a dystopia today depends on where we’re sitting.

A banker’s utopia is a factory worker’s dystopia. Utoptic gated communities which do not permit low-income residents are utopic only for the few who live there. They do not fix the wider problem of crime and poverty. They simply push it out to the fringes, where they can’t see it.

But unseeing a thing doesn’t make it disappear.

In truth, pushing people aside, locking them away, putting them into ghettos, erasing them from stories, does far more harm than any amount of seeing will do.

Because what we see we actually have to acknowledge as a part of the wider story, the wider culture.

What we see is us.

Art by Olivier Malric

I write stories. It’s what I do. It’s what my colleagues do. By day I craft marketing and advertising copy that’s still mostly white, mostly ableist, mostly upper middle class, assumed heterosexual. Mostly male.

Heroes can have limitations of mind, of body, limitations imposed at birth, by circumstance, or by society, and still be heroes. They can be all of this and more.

But as the voices we see and hear every day become harder to ignore, harder to unsee, that is changing too. I can put different people onto the page, and use different language – not just at my day job, but my night job, too. My novels can give you a hero of either or other or no gender, from a variety of cultures of every type and hue and practice. My heroes can have limitations of mind, of body, limitations imposed at birth, by circumstance, or by society, and still be heroes. They can be all of this and more. They can be seen.

And publishers will buy them. And readers will read them.

My fear of being unpublished, pushed out, ignored, because of who or what I write about is fading.

This is changing not because the people themselves are there any more or less than they (we!) used to be. The world has always been a diverse and interesting place. But with the rise of social media and instant communication platforms, it’s easier to organize and speak out. It’s easier to come together. It’s easier to insist on being seen. It’s harder to forget or wipe away the history that brought us all to the places we started this life within, the cultural constructs that bound us. The constructs we are working so hard to unmake, refute, challenge.

So if you find yourself wondering why so many of us ask to be included now, and put ourselves and others into stories we’ve been written out of, perhaps, first ask why that inclusion is considered political, but the erasure was not: the laws, the asylums, the housing policies, the repression, the abuse.

There is nothing more political than erasure. Than unseeing.

The world is not changing. It’s been this way all along. We have been here all along. All that’s changing is what you see. You just never saw us. I never saw us.

I, for one, have hungrily sought out that fuller picture, and am working hard to contribute to showcasing it. However fraught and horrifying it often is, it’s the one we live in. It’s the one we must work with.

It’s the one we must change.

But we can only reimagine the world if we see the one we’re actually living in.

*Further reading on the origin of this title choice.

[…] “What We Didn’t See: Power, Protest, Story” Hosted by A Dribble of […]

Every time I see a new post from you, it feels like finding chocolate in the fridge that I don’t remember having put there. It makes me happy.

Keep writing. Keep showing us who we are.

[…] What We Didn’t See: Power, Protest, Story – from Kameron Hurley’s current blog tour […]