Zhuangzi and Huizi cross a bridge over the Hao river. Minnows dart below, silvery and swift. Zhuangzi leans so far over the railing he almost falls. “They swim about so freely—they go wherever they like. That’s happiness, for a fish.”

Huizi crosses his arms; he realizes he’s wrinkling his silk gown, and crosses his arms differently so the gown’s sleeves hang smooth. “You’re not a fish,” he says. “On what basis do you claim to know what fish like?”

Zhuangzi turns back and raises one eyebrow in that way he knows pisses Huizi off. “You’re not me. On what basis do you claim to know what I know?”

We’ve all been there.

We sit across from a friend or an enemy at dinner, standing beside an acquaintance in a bar, we lean against a con party wall, we walk side by side along the river with a lover or a friend. Maybe the conversation skidded out when one of us mentioned unions or the inheritance tax, expecting reflexive “oh sure” agreement and finding a defensive, pointed entrenchment; maybe we’re talking about our feelings and they’re not listening; maybe they said something we find unconscionable, or the other way round. And we feel that hot pressure behind our forehead, because they are just… not… getting it.

We’re homo sapiens on paper, but sapientia’s worth squat without communication. When the first proto-human had her first thought, she looked around for someone to share it with. How many times do you think we, as a species, got that far without reaching the next step—without managing to say “Hey, check this out?”

Cognition research suggests that animals do a lot more of it, cogitating I mean, than we used to think, which won’t surprise anyone who’s tried to keep a poodle in their back yard, so it’s hard to say when that leap happened. We made it back when we were habilis, if not earlier. (And we’re not the only ones who did—whales have languages and dialects.) But still, every once in a while I think about those occasional isolated nodes, the stars that burned before there were other stars to shine against. Think about the loneliness of having a thought and not being able to pass it along.

And we go back there again and again—at the table, at the bar, near the wall, by the riverside, and for all our hundreds of thousands of years of practice, the gap from mind to mind seems uncrossable.

How do we talk to one another?

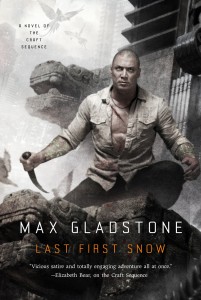

I wrote a book called Last First Snow, which is out now. It’s a fantasy novel about zoning politics, human sacrifice, and parenthood. There are battles of sorcery and wits and fists; there’s love and loss, tragedy and redemption; there are schemes and feathered serpents in abundance. Plot we’ve got, quite a lot, as the man says. But it’s also about how hard it is to talk.

The once-human wizards who rule the city of Dresediel Lex want to tear down an (in their eyes) decrepit district, an eyesore, a relic of the days when Dresediel Lex was ruled by gods now dead. The rebuilt Skittersill, they say, will be better—safer, more modern, easier to defend, more valuable, enticing to industry.

The people who live there now, don’t feel that way. For them, the Skittersill’s where they were born, where their parents were born, where their children will be born. It’s the place they work. When they come home, they know everyone on the block. That’s what makes it good. So when a bunch of wizards show up claiming they know what will make the Skittersill better…

Both sides are right, from their perspective. For the wizards—the Craftsmen—the Skittersill’s in a bad state, and must be improved. For the people who actually live in the place, “improvement” looks a lot like destruction. On a literal level, the two sides speak the same language, but the words they use mean different things. In a way that makes communication even harder than if they simply spoke different languages—if one side spoke German and the other Swahili, they’d pretty quickly cotton on to their need for a translator.

Instead, they face one another across a protest line, and struggle to find common ground before they’re forced to fight.

We built science to communicate; science is, among other things, a system of definitions and relationships clear enough that scientists can, much of the time, understand what other scientists are saying. The requirement—well, it’s not really a requirement, let’s call it the notion—that scientific experiments should be repeatable boils down to the idea that a statement we think is true scientifically, should be true for everyone.

You can do a lot of cool stuff when you have a body of statements that are hold true for everyone. Since calculus and chemistry and aerodynamics work the same for everybody, we can build rockets and semiconductors and particle accelerators. Moving mountains—literally moving literal goddamn mountains—becomes trivial.

In fact, this is so helpful that we tend to assume, as a culture, all statements are scientific, which is to say, universally true. “I’m angry about this,” our friend says, and we think he means, “you should be angry too, in the same way I am,” and say “Well, I’m not,” and he hears, “You aren’t, not really.”

And then he really is.

What better options do we have?

Huizi is not amused.

“I am not you,” he replies to Zhuangzi. “Of course. So I don’t know what it is to be you. But I do know that you’re not a fish. My point remains: how do you know what fish like?”

Zhuangzi is a philosopher of freedom and play. Zhuangzi tells the story you may have heard about the useless tree—too thin to make beams, too gnarled to make boards, too ugly to carve, its fruit too sour to eat. Which turns out okay for the tree, in the end, since no one cuts it down or harvests its fruit! So, says Zhuangzi, what’s wrong with being useless?

Zhuangzi teaches through stories, which makes him a philosopher after my own heart. He doesn’t so much wrap philosophy in jokes as tell jokes that are, at the same time, philosophies.

Huizi is a real philosopher, too—a teacher of rhetoric, propositional logic, and paradox. “His writings would fill five carriages,” says one contemporary account, but none of those writings survive. He’d likely be closest, in modern philosophy, to a dialectician or maybe a sophist.

The story I’m telling here’s from Zhuangzi’s body of work; Huizi, in classic sophist mode, presses Zhuangzi on his definitions, on the origins of his knowledge and the basis for his claims. When Zhuangzi tries to spin his arguments, Huizi presses further. He wants clarity, dammit.

Zhuangzi turns back to Huizi and leans against the rail. Golden light falls between them.

“Ah,” says Zhuangzi. “But that’s not what you asked first. You asked me on what basis I claim to know what fish like. I claim to know it—“ and he stamps the planks underfoot—“on the basis of this bridge, over the Hao River.”

That’s where the story ends, as written—that quick zinger, Zhuangzi turning Huizi’s own argument against him through fast grammatical footwork and a textual loophole.

We don’t see Huizi’s reaction. Maybe he doesn’t get the joke. Maybe he doubles down, says that Zhuangzi’s just dodging the question. Maybe he decides, I don’t want to talk with this guy any more. He doesn’t speak my language. Huizi could go back to his own disciples—people who agree with him about how to talk, and how to argue, about what counts as known and what unknown.

I strongly suspect this is how the story ends:

Huizi laughs.

Huizi shows up throughout Zhuangzi’s writing, generally arguing with the teacher himself. They rarely agree. They poke fun at one another, they bend and subvert one another’s ideas. Zhuangzi gets the best of his rival most of the time, but that’s to be expected. Zhuangzi, after all, is the one writing the book.

Later in life, passing Huizi’s grave, Zhuangzi says, “Since you died, Master Hui, I have no material to work on. There’s no one I can talk to any more.”

While Huizi’s mentioned frequently in contemporary accounts and indexes of philosophy, those “five carriages” worth of teachings have not endured. His thought survives only in Zhuangzi’s writing—which includes the ten paradoxes Huizi taught his students, and this story about the fish, one of the most enduring vignettes from Zhuangzi’s own philosophy.

These two spoke very different languages, but they seem, at least, to have been able to talk with one another.

Laughter isn’t always the answer. Sometimes we have to stand up for ourselves, or for our friends. Sometimes we need to push.

But the point of the dialogue over the Hao isn’t that humor is the only response to tension—it’s that language is a fundamentally imperfect instrument. It squirrels around us and wriggles out of our grip. The more convinced we are of the completeness of our language, of our argumentative style’s sufficiency in all situations, the more brittle that language, and the more it serves as a wall. We lean on our certainty in uncertain situations, rather than understanding the limits of our knowledge; we hold our words like torches before us, and in that process, we burn others—and ourselves.

If we’re lucky, we realize it in time.

We’re not always lucky.

I love reading the guest posts he’s been writing for this blog tour, because they’re brilliant and insightful and so much fun to read!

[…] Happiness for a Fish “But still, every once in a while I think about those occasional isolated nodes, the stars that burned before there were other stars to shine against. Think about the loneliness of having a thought and not being able to pass it along.” […]