One Thousand and One Nights, or, as it’s often better known in the English speaking world, Arabian Nights, is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. The basic premise is that a Persian king discovers his wife’s infidelity and has her executed. Deciding all women are the same, the king marries a series of virgins only to execute each one the next morning, before she has a chance to cuckold him. Eventually the vizier cannot find any more virgins until his daughter, Scheherazade, volunteers herself as the next bride. On the night of their marriage, she begins to tell the king a tale, but does not end it, forcing the king to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins a new one, and the king, eager to hear the conclusion, postpones her execution once again. So it goes on for 1,001 nights.

Built around that frame story, Scheherazade narrates historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques, and even erotica. The book in its entirety demonstrates many innovative literary techniques like the aforementioned frame story, embedded narratives, foreshadowing, and unreliable narrators. Thematically, the stories heavily utilize fate and destiny, most prevalent being the notion of the self-fulfilling prophecy. Elements of genre tropes from crime fiction, horror, and science fiction, pop up frequently. The stories aren’t just incredibly compelling, but they paint a much different perspective of the Islamic history and culture than Western perception might imply.

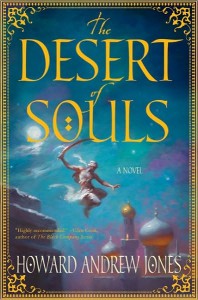

This is a review about The Desert of Souls by Howard Andrew Jones, or at least it was when I started it. The truth is I can’t talk about one without the other.

The Desert of Souls is the story of two common men — Asim and Dabir — in 8th century Baghdad. It begins with a strange plea to the vizier to safeguard a relic from falling into the wrong hands. The vizier tasks his resident scholar, Dabir, to unlock the mystery. When the relic is stolen, both Dabir and Asim are sent to retrieve it. Along the way they’ll struggle against fate and destiny, and their fair share of monsters. While written very much in a sword and sorcery tradition, Jones’s debut novel is more the adult version of Disney’s Aladdin (sans Robin Williams and Gilbert Godfrey) than a Middle Eastern Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, utilizing the tropes and structures from Arabian Nights to accomplish a modern interpretation.

The main motive power of the narrative comes from the mystery surrounding the relic. At its core, The Desert of Souls is a crime thriller. Laced around its edges are elements of both horror and science fiction, most of which comes from interactions with the fantastic, be they djinns, magic powers, necromancy, or annoying talking parrots (just kidding, it’s really a giant snake). Jones ups the ante by challenging his characters early on with a fortune teller who reveals their fates further paying tribute to Scheherazade’s tales.

The main motive power of the narrative comes from the mystery surrounding the relic. At its core, The Desert of Souls is a crime thriller. Laced around its edges are elements of both horror and science fiction, most of which comes from interactions with the fantastic, be they djinns, magic powers, necromancy, or annoying talking parrots (just kidding, it’s really a giant snake). Jones ups the ante by challenging his characters early on with a fortune teller who reveals their fates further paying tribute to Scheherazade’s tales.

Jones doesn’t stop with just the flavor of Arabian Nights, he also uses similar structures and literary traditions. Although not couched as a frame story (a la Rothfuss’s The Kingkiller Chronicles), Jones tells his story via a first person narrator that recognizes himself as a storyteller. Asim is frequently self referential, acknowledging his role in the telling and his capabilities therein. Jones likewise treats the reader to ‘stories within stories’ that recount Asim and Dabir’s earlier adventures. As one ended, a question arose:

Jones doesn’t stop with just the flavor of Arabian Nights, he also uses similar structures and literary traditions. Although not couched as a frame story (a la Rothfuss’s The Kingkiller Chronicles), Jones tells his story via a first person narrator that recognizes himself as a storyteller. Asim is frequently self referential, acknowledging his role in the telling and his capabilities therein. Jones likewise treats the reader to ‘stories within stories’ that recount Asim and Dabir’s earlier adventures. As one ended, a question arose:

Mahmoud drew close. “Last time you told the tale, the dead king called forth a demon with a man’s and you fought it while Dabir struggled through the magic circle.”

“Well,” I said, “a good storyteller tailors his story for his audience.”

A short passage, but one that calls into question the veracity of the entire narration.

I would be remiss if I didn’t credit Jones’s other inspiration, and one that he has often cited as the managing Editor of Black Gate Magazine. Much of the pacing and action can be credited to his love of Robert E. Howard (and his disciples). I couldn’t put it down once I started it, carried forward by the enthralling pace and engaging prose. I was invested in the fate of the characters despite the choice in narration that assured their survival. The final product is something that isn’t just a ‘Middle Eastern Fantasy’. It’s a novel that honours the time honoured themes and techniques on which today’s stories rest.

A masterful novel that resonates on a visceral and meta-fictional level that’s rarely equalled.

It embraces the past, infused with Arabian Nights and early 20th century fantasy, but not at the expense of good storytelling. None of the purple prose predilections of either era make their way into Jones’s text. He relies on excellent technique, building his world through sensible character interaction, dialogue, and his clever use of the ‘story within a story’. Many will call Howard Andrew Jones a writer of historical adventure fantasy. It’s an accurate description, but one that sells him woefully short. The Desert of Souls is a masterful novel that resonates on a visceral and meta-fictional level that’s rarely equalled.

Earlier today that praise was echoed from an unexpected quarter when Jones announced his series, now titled Chronicles of Sword and Sand, had been option by a major film studio. There’s a great deal to be said for the cinematic opportunities in the novel, but I think we can all agree that nothing would be worse than a repeat of the Prince of Persia starring Jake Gyllenhaal. Regardless, The Desert of Souls, is one of those novels I cannot recommend enough.

One of my favorite discoveries recently in genre has been Howard’s work.

I love the hardcover art and I wish that style was being carried throughout the series. I can’t understand how the bad-CGI looking crap they replaced it with sells more books.