Epic Fantasy is in the midst of something of an identity crisis. See, mainstream readers love to lap up recognizable tales of valourous kitchen boys, big magic, elves, dwarves and warring kingdoms. Such novels sell like hotcakes, and publishing companies love them. And why not? We all grew up on it, didn’t we? Terry Brooks, Raymond E. Feist, Barbara Hambly, or Tad Williams — they built worlds unlike any we’d ever seen before. On the other hand, there are more critical fans who, perhaps, associate their love of Fantasy with an ever-expanding need to find works that push the boundaries of imagination, explore the issues of culture, politics and gender in our world through the lens of an imaginary universe where rules are different, where freedom and fairness might exist.

There have always been authors who push against these boundaries set on the subgenre by its legion of fans. Early in her career, Robin Hobb released the Farseer trilogy, which took the foundations built upon by Tad Williams and Robert Jordan and refined and redefined them, crafting a world and genre that was familiar, but spun the tropes (kitchen-boy-turns-king becomes bastard-prince-becomes-assassin; not an elf or dwarf in sight and conflicts that are cultural, rather than racial) in new, interesting ways. Going even further back, Terry Brooks revitalized Fantasy from its post-Tolkien doldrums by effectively re-telling modern Fantasy’s greatest tale, but, alongside him was Stephen Donaldson and his The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, the Unbeliever trilogy, a work with similar roots to Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara, but an entirely different interpretation and subversion of genre tropes. While pushing the genre forward isn’t entirely anathema to commercial success, it’s a rare few authors who have managed to capture lightning in a bottle with their daring works.

So, the genre struggles between two sets of fans: those who seek comfort, and those who wish for more, for something more daring. One set of fans seeks to recapture the excitement of their youth by re-living the same stories retold, the other searches always to discover that feeling of something new, something as wondrous and alien as the first time they jumped into Middle-earth, or their own Fantasy world of choice.

Samarkar felt unreal, as if she had become someone out of a story. She might have been mist, blown through the corridors on a gale.

At least, these are the two factions that war within my inner fan.

At least, these are the two factions that war within my inner fan.

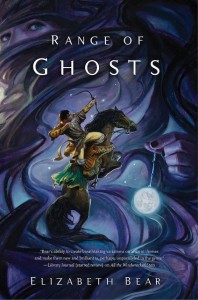

More than any other novel I’ve read in recent years, Range of Ghosts brings intense satisfaction and excitement to those two sides of my fandom. I do not say this lightly, because I consider him one of Fantasy’s modern masters, and readers of this blog will know that I hold his work in highest regard, but reading Range of Ghosts reminds me of Daniel Abraham’s finest works and the addictive enthusiasm that his novels hold over me. There’s adventure and great feats of magic in Range of Ghosts, equal to anything found in the ’80s hey-day of Epic Fantasy. Couple that with grand, sweeping worldbuilding that breathes life on every page, and you’ve a novel that will excite even the most jaded Fantasy fan.

Beyond that, however, Range of Ghosts is a novel that succeeds also on the subtle character building that defines the most thoughtful works of Fantasy, or, really, any sort of fiction, any medium. The characters of Range of Ghosts are subtle and achingly damaged. Temur and Samarkar, the novel’s two main protagonists, are caught in a war forced on them by the circumstance of their birth. Both of royal blood, Samarkar and Temur both struggle with the duty and responsibility of their elevated place in the world in different manners. Samarkar, not through weakness, but instead in an effort to create a place in the world for herself, a place where she can be powerful, flees from her royal blood through abdication and taking up the celibate ways of a Wizard. Temur, his family slaughtered in an intense civil war, and hunted by his ruthless kin, who seeks to rule their people, drives forward to his destiny, spurred by both a desire to recover what was taken from him and to right what he feels is a wronged world. Their motives are entirely different, but Bear slowly and quietly brings the reader to understand that, at the very core, these two are fighting for the same thing, and are driven by many of the same values.

Samarkar is a particularly interesting diversion from the average female featured in so many Epic Fantasy novels. A wizard of moderate magical strength, Samarkar is often remarked upon not for her magic, but for both her size and strength of her body. One passage in particular stood out to me, when Samarkar first meets Temur:

He wasn’t a big man, and she thanked her luck for that. And she thanked her ancestors that she was a big woman, broad-hipped and broad-shouldered, with strength in her arms and thighs. He was wasted with sickness and hard travel, as well, and so she managed to stand him up to where he could grab the bay mare’s saddle, then help him heave himself back into it. The mare stood like a statue, her master slumped forward over the waist-high pommel, and Samarkar steeled herself to approach the nervy gray.

p. 134

“A good thing they didn’t know I was traveling with a trio of warrior women. I wouldn’t have stood a chance alone.”

Here is our hero, a courageous warrior in the prime of his youth, and Bear writes a woman who helps him not through her motherly qualities, or her learned skill as a healer, but through physical strength and the instincts of a well-travelled and capable survivalist. Many times throughout the novel, the women and girls, for Payma, who appears late, pregnant and valorous in her escape, is barely out of childhood, show as much persistence, knowledge, physical strength and intelligence as the male characters. These are no damsels-in-distress. Even the one character, who is, almost literally, a damsel-in-distress, shows her own initiative in escaping her captors, hoping, but not waiting for rescue by her knight-in-shining-author.

Gender, and the breaking down of the expectations of the genre, is of clear importance to Bear, as evidenced by Temur’s musings throughout the novel. One short passage addresses the issue directly:

Temur felt a spike of pity for her, and by extension for every woman murdered in games of power where she was awarded no control. But perhaps that wasn’t fair to the women: His mother might have been traded away as a spoil of war, but she had risen high in his father’s councils and consideration, and certainly the Great Khagan had never scrupled to ask his mother’s advice.

And Nilufer, as Samarkar had so aptly reminded him—she had taken on bandits, rebels, and her own mother to make a safe haven for herself. No, women were as capable—and as dangerous—as any man. Sometimes more so.

And a good thing, too, since you are stuck in the dark with three of them. If Hrahima could be reckoned as a woman, in this accounting.

p. 223

Also explored in the novel is the crossing of culture and custom in a post-colonial and post-conquest setting. Temur’s people, the Quersnyk are a fearsome people who drive forward and conquer their neighbours with little mercy. Their purposes, however, as the reader is reminded of several times throughout the novel, are not cultural or societal, they do not question the beliefs and practices of those they conquer, and allow them to continue to live as they had, but are purely financial. They conquer for power and gold. Temur at one point muses about the nature of his people:

[I]t was the Qersnyk way not to question too much the customs of others but rather accept them as they found them—so long as they bent their heads to the Khagan. His people conquered for riches and knowledge, not to evangelize.

And if the Uthman Caliphate warred against itself, well, that made things all the better for the Qersnyk clans, didn’t it? An enemy divided was easy prey. But now Temur’s people had fallen into the same trap, and if the Cho-tse could be trusted, that division was being encouraged by equally predatory outsiders.

How long would a Rahazeen master allow Qori Buqa to rule unbowed? How long before the proud Qersnyk Empire became a vassal state to some western warlord?

The Great Khagan himself had started life as a simple herdsman. It was not unheard of for great empires to grow from humble beginnings. The Qersnyk tribes could find themselves a vassal state as easily as they had made vassals of other lands.

p. 158

And again, in the clashing of beliefs and lengends, as Samarkar discuss the Carrion King, a mysterious mage-prince who seems to be lurking in the shadows at the edge of their conflict:

“Have you heard of the Carrion-King? Before I left, one of my brothers’ wives was reading about him. A kind of demigod, supposedly a Qersnyk.”

“Of course,” Temur said, bracing a foot on a stone and standing up on it. “But he wasn’t a Qersnyk; he was a sorcerer from Song or maybe one of the western horse clans. We call him the Sorcerer-Prince. In my homeland, they say he fought the Warrior-Gods of the Uthman Caliphate, and Song, and Rasa, and Messaline, and defeated them all. But they also say that the sky was hung much higher in those days. In the battles, the four ranges of mountains that supported the Eternal Sky’s pavilion were damaged, so the Sky’s roof sagged. And then the Sky came out to see what was the matter and put the Sorcerer-Prince in his place.”

Struggling up the same rock, careful of the lead lines she was trailing, Samarkar said, “That’s not how we tell it in Rasa.”

Temur snorted like his mare and said complacently, “Of course not.”

p. 167

These questions of gender, culture and politics challenge the reader to engage more closely with the world Bear is creating, but are used lightly and deftly enough that they never bog down the narrative with Bear’s own personal opinions or rhetoric. It’s just enough to get you considering the conflict from the sides of all involved. These are not ‘good guys’ fighting against ‘bad guys,’ but various groups of people trying to negotiate a world that is harsh and rewards only those with the skill and knowledge to survive and stay ahead of the politics and frightening magics that ripple through the various warring countries.

On the other hand, Range of Ghosts is full of magic-summoned armies of hungry ghosts, lightning-charged caterpillars the size of elephants, Wizards able to conjure water from desert air and magical rings of invisibility and scorpion-herding (take that, Sauron!). This is a novel that enjoys its ability to draw from myth and its roots in the ancient, fantastical stories of the Asian steppes. As it progressively pushes the genre forward, Range of Ghosts also revels in the history of the genre with a breakneck pace, and action and magic littering every page. This is fun and intelligent.

“Her name is Buldshak,” he said, gesturing to the rose-gray. He pointed to the liver-bay with his chin. “And her name is Bansh.”

“Bansh? It’s not a word I know. What does that mean? Something like ‘Fearless’ or ‘Sword of the Wind’?”

Temur looked down at his feet. “‘Dumpling,'” he said. “It means ‘Dumpling.'”

But Samarkar didn’t laugh—or she didn’t laugh cruelly. Instead she looked at the bone-thin mare and said, “She likes her dinner, I take it.”

p. 163

“Wait a minute,” Payma said, swinging her awkward belly over the saddle to dismount. “While we’re stopped, I have to pee.”

Something I did not expect was the subtle touch of humour that underlies the novel’s serious nature. This humour helps to pull back the curtain on people in troubled times and gives the reader a glimpse at who they are under normal circumstances. In their own ways, each of the novel’s central characters have their own sense of humour and Bear does not gloss over this important aspect of human nature that allows us to deal with the traumatic events that take place during war times. Many horrible things happen in Range of Ghosts, and it says much about Samarkar and company that humour can be found in such trying times.

There is a trend in recent Fantasy to base worldbuilding on recognizable real world inspiration, featuring low levels of magic, inspired by the success of authors such as George R.R. Martin and Joe Abercrombie. Range of Ghosts, however, has no fear of playing with grand magic and the wondrous elements that are avaiable only to Fantasy novels. While Bear obviously drew inspiration for her world, its cultures and the foundations of her story from parts of Asia, with hints and names that suggest it might be our own in a different age if you squint hard enough, she has created a truly unique and mystical world out of those pieces. This is legend brought to life, with all the grandeur associated with creation stories from the various cultures that Bear draws inspiration from. This is a world where the sky has a voice, tigers walk upright and speak, and ghosts are risen from the untended fields of battle to serve the whims of villainous sorcerers.

This is a world of myth.

Expansive without being bloated, intelligent and accessible, this is Fantasy at its best.

To those that claim Epic Fantasy is too conservative, relies too heavily on tired tropes, or has grown stagnant, I say, read Range of Ghosts and discover the best the genre has to offer. Expansive without being bloated, intelligent and accessible, this is Fantasy at its best and will appeal to fans of authors ranging from Daniel Abraham and N.K. Jemisin, to Terry Brooks and Tad Williams. Range of Ghosts is wonderful and compelling, a truly great novel that moves the genre forward by challenging and embracing its history all at once. I wait with little patience to get my hands on Shattered Pillars and Steles of the Sky to discover the end of Temur and Samarkar’s journey.

Thanks, Aidan

While her world is based on Central Asia (“Silk Road Fantasy” as I call it), it definitely is unique. Once I realized that each realm had its own astronomy/cosmogony/cosmology, I really fell for this book, hard.

This has been sitting in my audio queue for some time now…invoking Abraham may have just bumped it up closer to the top!

[…] is Elizabeth Bear following up the best epic fantasy trilogy of the past decade? With a rip-roarin’ standalone Steampunk novel about a prostitute with a […]