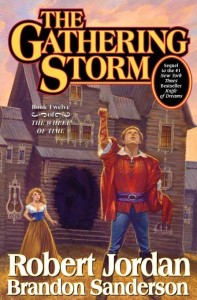

Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series has been one of the most sprawling, character-intensive epic fantasies of the past twenty years. Spanning millions of words, this series, now reaching its twelfth volume out of a planned fourteen, has spawned dozens of fansites over the years, as well as engendering heated debates over matters ranging from how well (or not) the author managed to portray female characters to questions of character identities and motivations to even a fictional murder-mystery that still remains unresolved seven volumes after its occurrence. Some view passages, such as the (in)famous “wind passage” that opens the first chapter of each book, as being hallmarks of a great talent. Others read the same lines and wonder how the story ever managed to become even more turgid and bloated than the previous volume.

One of the most sprawling, character-intensive epic fantasies of the past twenty years.

Debates such as these point to some intrinsic quality of the series that barely allows for there to be a middle ground. There is something for almost everyone, depending if one likes an action/adventure tale, political intrigue, social commentary, or even elements of a puzzle novel. Sometimes, there is too much of it all, and readers who enjoyed the earlier volumes might end up finding the past few volumes to be rather plodding, tedious affairs. After reading the eighth and ninth volumes, The Path of Daggers and Winter’s Heart, I found myself going years before even thinking of picking up the tenth volume, Crossroads of Twilight, which was perhaps the most difficult book to complete reading of them all at the time.

Would Sanderson manage to capture Jordan’s narrative “voice,” warts and all, and [would] the conclusion be worthy of the time invested in the series?

But then a tragic event happened. Jim Rigney, the person behind the Robert Jordan pseudonym, contracted a rare blood disorder, amyloidosis. Rigney spent the final eighteen months of his life battling the disease, while attempting to complete the conclusion to the series. Sadly, he succumbed to the disease on September 16, 2007. Fans were devastated, as for nearly three months, the matter of who would complete the series, or even if the series would be completed, was up in the air. Toward the end of the year, Rigney’s wife, Harriet McDougal, announced that she had chosen young author Brandon Sanderson, whose work to date had been three adult fantasies (Elantris and the first two Mistborn novels) and two young adult novels. Wheel of Time fans were probing for information, trying to decide if Sanderson was the “right” choice, if he would manage to capture Jordan’s narrative “voice,” warts and all, and if the conclusion would be worthy of the time invested in the series.

Sanderson’s interpretations of the two main characters of this story, Rand al’Thor, the Dragon Reborn, and Egwene al’Vere, the rebel Amyrlin, are almost pitch-perfect.

Depending on what you enjoy most about the series, Sanderson largely succeeds in this thankless task. For those wanting to know if Sanderson would manage to capture the essence of the late Jordan’s writing style or if his passages would integrate well with the ones Jordan had completed before his death, it will be difficult for most of the time to discern which author wrote which passage. Sanderson’s interpretations of the two main characters of this story, Rand al’Thor, the Dragon Reborn, and Egwene al’Vere, the rebel Amyrlin, are almost pitch-perfect. What I found interesting about Sanderson’s treatment of the characters is just how well they are integrated with Jordan’s earlier development of them.

Rand in particular has a very good character development arc in The Gathering Storm. Hurting from his myriad mental, emotional, and physical wounds, he is a near-complete wreck. Increasingly paranoid and worried that he is not “hard enough” to face the Dark One in the prophesied Last Battle, Rand’s character displays many traits in common with soldiers suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder during the Vietnam War. This is no accident, as before his death, Rigney discussed how he himself faced a decision in Vietnam if he was to desensitize himself to the horrors happening around him or if he would fight to keep from becoming a sociopathic killer. Rand’s development from the first chapter, “Tears from Steel,” to the last, “Veins of Gold,” is one of the more intriguing in the entire series. It is perhaps for me the most personal of all the mini-plots in this mammoth series and the authors do such a good job of showing Rand’s descent into darkness, both figurative and literal, as well as setting up the decision he makes at the end of this book that is in many ways as important thematically as the cleansing of saidin was in Winter’s Heart.

Paralleling Rand’s development and his struggles to integrate his past and present memories is that of his childhood sweetheart, Egwene. Captured at the end of Crossroads of Twilight and forced to undergo numerous punishments at the hand of her rival for the head of the Aes Sedai organization, Elaida, Egwene presents a clear contrast to Rand’s choices early in the novel. Instead of trying to harden herself by means of shutting out friends and even one’s own emotions, Egwene comes to accept her situation, viewing matters such as hurt and grief not as something to avoid or to manipulate, but rather as things to accept and to use to improve one’s self. This change from the rather ambitious, self-righteous girl of the earlier volumes into a leader who realizes the importance behind the very name of “Aes Sedai,” stands in sharp opposition to that of Elaida, as the authors go to great lengths to make clear in the second chapter, “The Nature of Pain.”

Paralleling Rand’s development and his struggles to integrate his past and present memories is that of his childhood sweetheart, Egwene. Captured at the end of Crossroads of Twilight and forced to undergo numerous punishments at the hand of her rival for the head of the Aes Sedai organization, Elaida, Egwene presents a clear contrast to Rand’s choices early in the novel. Instead of trying to harden herself by means of shutting out friends and even one’s own emotions, Egwene comes to accept her situation, viewing matters such as hurt and grief not as something to avoid or to manipulate, but rather as things to accept and to use to improve one’s self. This change from the rather ambitious, self-righteous girl of the earlier volumes into a leader who realizes the importance behind the very name of “Aes Sedai,” stands in sharp opposition to that of Elaida, as the authors go to great lengths to make clear in the second chapter, “The Nature of Pain.”

There are even more parallels between the characters along the lines of examining the choices people make in regards to themselves and others. It is debatable whether or not Jordan would have been quite as direct as the final draft came to be, but several times over the course of the novel, characters ranging from the two mentioned above, Perrin, Mat, and members of the Black Ajah and the Forsaken are shown via the choices they have made. The selflessness of one clashes with the self-centered greed of another. The desire to be viewed as being important contrasts with one who humbles herself, placing her own soul in risk of eternal perdition so the machinations of others can be revealed to others. These parallels, which were either lacking or were not adroitly done in the past several volumes, helped make The Gathering Storm one of the better Wheel of Time volumes I have read in the past twelve years.

Mat’s chapters […] felt rather sketchy, as if Sanderson had not decided what to do with the character in the allotted space.

Despite this, there were several problems that I had with the text. Although Sanderson eschewed the character “blocks” that Jordan used in the past few volumes, there were times that the pacing of the plot still suffered. While Rand and Egwene’s subplots were developed well and each concluded within narrative minutes of one another, Perrin and Mat’s were underdeveloped and appear to be days or even weeks behind the first two. In addition, their characters were not as well developed as were Rand’s and Egwene’s. Perhaps this is in part due to the limited number of chapters each appears, but Mat’s chapters, despite a near-horrific chapter occurring in a backwoods town near the kingdom of Andor, felt rather sketchy, as if Sanderson had not decided what to do with the character in the allotted space. Perrin’s arc was rather anti-climatic and it is hard to guess where he will be heading in the next volume. Despite the near-certain protests from fans of those characters, The Gathering Storm might have been better served if those arcs had been withheld until the next volume, even though that alternative certainly would have risked backlash from those burned by the eighth and tenth volumes of the series.

The pacing was mostly good, although there were times that events long foretold in the series unfolded so quickly that there was a sense of a letdown. But perhaps reader expectations had been built up too much from the narrative molehills, so it is hard to say particularly which events (ranging from what occurred outside a castle in Arad Doman to the use of a certain item discovered in The Shadow Rising) were done too hastily and which events were done purposely at such a breakneck pace in order to set up future character development. For myself, the two events I allude to above served to develop Rand’s character in ways that were at once surprising and logical in hindsight (especially as it relates to how he parallels Moridin more and more now in thought and action). But others might view these scenes differently, wishing that Sanderson had spent more time setting up the events so that there would be a stronger emotional reaction. There is something to be said for this argument, but I suspect if there had been further development of these two set scenes, the pace of the narrative would have slowed to the near-glacial creep of the previous novels.

Prose is something I value highly in a novel. The previous eleven volumes of the Wheel of Time series were uneven to me, as powerful scenes would be offset by descriptions of clothing, of how to wash silk, and even lengthy scenes set in a bathtub. Sanderson’s prose in his novels tends to be rather too sparse at times, attempting to be too “invisible” when the occasional use of more florid language might serve to vary the prose enough to make it more interesting. Thankfully, for most of The Gathering Storm, Sanderson managed to achieve a happy medium between his own preferred style and that employed by Jordan. There are places where the narrative still feels clunky or choppy, but these are fewer than what I recall being present in Sanderson’s own work. The too-long descriptions of places and dress still occur on occasion, but thankfully they are reduced. The male characters’ self-conscious thoughts about their abilities with women is also much reduced, doubtless to the delight of numerous readers. While certainly not written in a style that would lend itself to being studied by writing students, the prose here was at least acceptable and at several times, very well-written.

Highly recommended for Wheel of Time fans and recommended for those who might have become disillusioned by the previous four volumes.

The Gathering Storm certainly is not an ideal beginning place for readers curious about the Wheel of Time universe, but for those who were disenchanted by the perceived lack of plot and character development over the past few volumes, it certainly is one of the faster-paced, better-written volumes. While I would not consider it to be among the best works released in 2009, it certainly is one of the best epic fantasies that I have read. The Wheel continues to turn and thankfully it appears to be cranking a bit faster and toward a more intriguing conclusion than I had suspected when I had suspended my reading of the series back in 2000. Highly recommended for Wheel of Time fans and recommended for those who might have become disillusioned by the previous four volumes.