In the world of tabletop fantasy roleplaying games, Pathfinder needs no introduction. Spawned from a group of developers seeing opportunity in the RPG space after the release of the 4th Edition of Dungeons & Dragons, Pathfinder — using the beloved Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 Edition ruleset — has become one of the most popular RPGs in the world in just six short years.

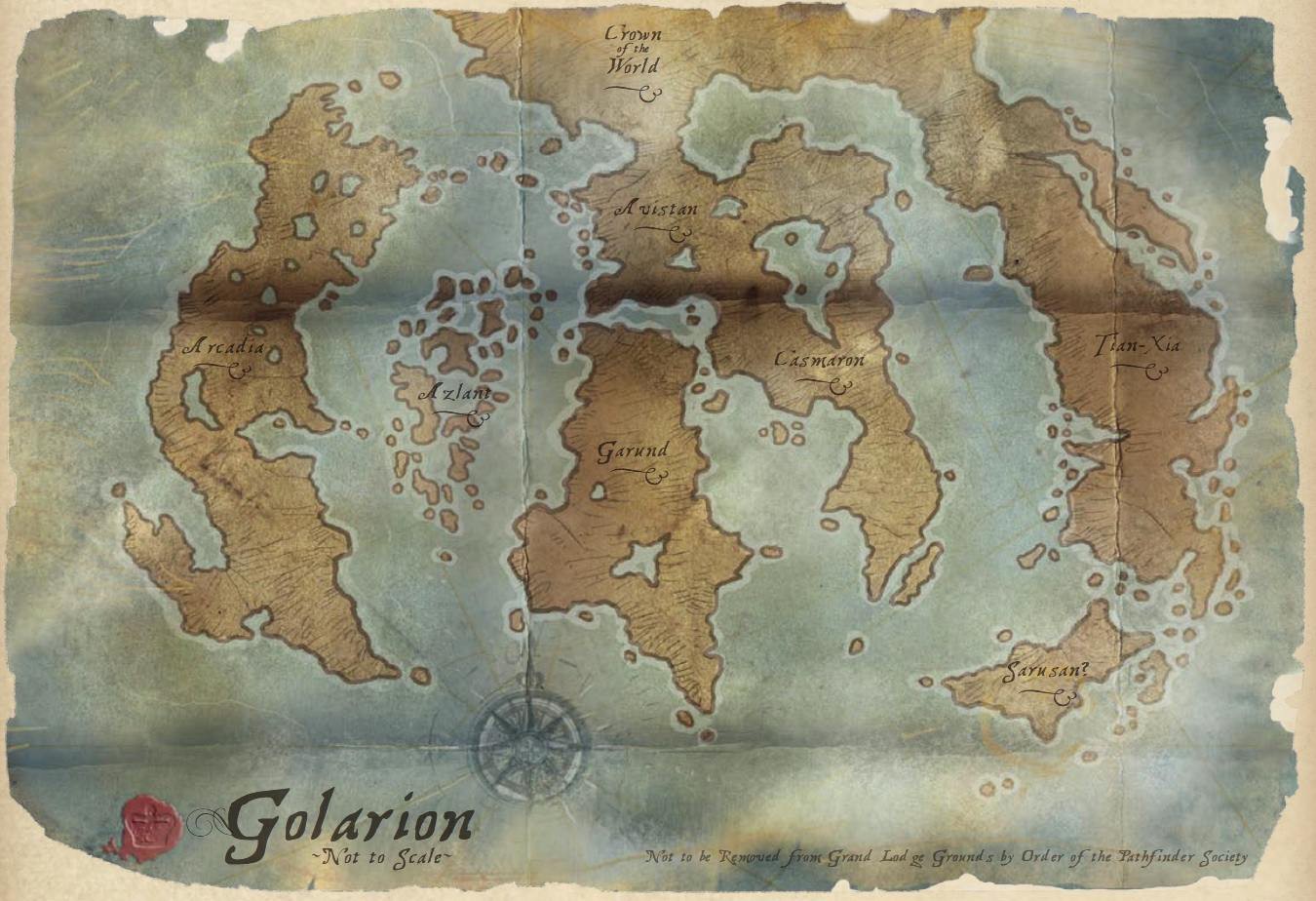

Set in Golarion, a sprawling world with so much depth that even the most jaded fantasy reader is sure to find something that interests them, Pathfinder is so much more than just a tabletop RPG — it’s a setting for some of the best Sword & Sorcery novels being published today. With names like Tim Pratt, Max Gladstone, Liane Merciel, and Howard Andrew Jones attached, the Pathfinder Tales line of novels offers great adventure, magic, and pedal-to-the-metal action from some of fantasy’s most exciting writers.

So, I caught up with James L. Sutter, Executive Editor for Paizo Publishing and a co-creator of the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game, to chat about Pathfinder, being a novelist, building a world, and encouraging gamers the world over to become storytellers in their own right.

Aidan Moher: Welcome, James! Can you introduce yourself for those not familiar with your work as a novelist and editor.

James L. Sutter: “Hey Aidan! My name is James L. Sutter, and I’m probably best known as a co-creator of the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game, as well as the Executive Editor for Paizo Publishing, where among other duties I’m the acquiring editor for the Pathfinder novel line from Tor and Paizo. As an author, I’ve written two Pathfinder novels — Death’s Heretic and The Redemption Engine — as well as a bunch of short stories published in places like Machine of Death, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Podcastle, etc. I’ve recently started doing some comic writing as well, for Dynamite’s Pathfinder series. On a non-literary note, I also really enjoy writing and performing music, and have played in a wide variety of projects from punk and metal to folk and musical theater.

“And since we’re doing this conversation-style, I’m going to ask YOU a question: When writing an introduction like this, do you think an author should include awards and accolades? If I were writing one for somebody else, I absolutely would — gotta tell the audience why this interview is worth reading — but doing it for myself makes me feel like a tool. As a *HUGO AWARD WINNER* — cue beam of light and angelic choirs — what do you recommend?”

Aidan Moher: Well, I wear my Hugo Award on a platinum chain around my neck — Flavor Flav-style — so, that tells you all you need to know about my perspective on awards. If you got ‘em, flaunt ‘em. Life’s too short for humility.

James L. Sutter: “The only reasonable choice! Yeah, I’ve been fortunate enough to win a bunch of game design awards over the years for my work on Pathfinder, but the thing that meant the most to me was when Death’s Heretic got chosen as #3 on Barnes & Noble’s list of the Best Fantasy Releases of 2011. It later was a finalist for the Compton Crook Award for Best First Novel and an Origins Award as well, but that B&N article was the first moment I could finally let out the breath I’d been holding since I started writing the book.

Aidan Moher: “I was using the office printer to print out some short stories I’d written, and Publisher Erik Mona found them and read them, and promptly assigned me a book, pointing out that it wasn’t conflict of interest if I didn’t have any say in the matter.”

James L. Sutter: “See, I’d never planned to write a Pathfinder novel. I felt like signing myself for a novel was cheating — how could I know if I actually deserved it? But then one day I was using the office printer to print out some short stories I’d written, and Publisher Erik Mona found them and read them, and promptly assigned me a book, pointing out that it wasn’t conflict of interest if I didn’t have any say in the matter. So I wrote the book, but was still extremely anxious about how it would be perceived. So when it ended up on a big-name best-of list with folks like Pat Rothfuss and Terry Pratchett, it was this huge moment of vindication. I could finally let myself believe, ‘Okay, maybe I did deserve that novel contract.’

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned about writing, it’s the importance of both humility and hubris. You need the humility to learn from those around you (and, you know, not be an ass), but also the hubris to refuse to internalize rejection, to believe that your stories are worth telling even when there are a thousand more accomplished authors out there.”

Aidan Moher: It’s interesting that you’ve won or been nominated for awards for both novel writing and game design. How do those two aspects of your job intersect? Do they conflict in any way?

James L. Sutter: “They intersect all the time — they’re essentially the same thing with different techniques, like playing guitar vs. bass, or painting watercolor vs. oils. In both of them, you’re trying to build a compelling world, memorable characters, an interesting plot. It’s just that when you’re writing an adventure, you don’t have the luxury of choosing exactly what the protagonists do. You have to prepare for more contingencies.

“As I recently wrote about on the Tor blog, most of what I know about world-building I learned from game design, working in close concert with some of the best setting designers in the business. They taught me that it’s always more interesting to ask questions than to answer them (though maybe not to the LOST extent). They showed me the power of the unexplained allusion, the importance of regimented magic systems, the joy of moral ambiguity, how to write an article where literally every paragraph is an adventure hook, etc. They also taught me how to be creative under pressure, which is invaluable — some of my best work has come from knowing I had a thousands words to fill and an hour in which to do it…

“For conflict — yeah, writing tie-in can be frustrating when you wish a rule worked differently, or you have to bend your ideas to incorporate someone else’s, but it’s also a blessing to get to create art as part of a team with people you really respect. And there’s also the time conflict — I’d be a much more prolific game designer or novelist (or bassist or guitarist) if I could just pick one and focus! But probably my favorite interaction between the two these days is when I run into a novelist I really respect for the first time — someone who’s just oodles better and more popular than I am, like Brandon Sanderson or Patrick Rothfuss — and while I’m trying not to geek out, they go ‘You’re one of the Pathfinder guys! I love Pathfinder!’ I won’t lie, that’s pretty great.

“Actually, I think that speaks to a larger idea, which is that it’s fun and useful to be more than just one thing. A piece of advice I have for new authors at conventions is: it’s one thing to define yourself as a writer out in the regular world, but when you’re at a convention where *everyone’s* a writer, it’s not very memorable. Other writers are probably more interested in hearing about your band or your cats or the funny story about the time you got caught in the bus door or whatever.

“God, I’m getting long-winded, aren’t I? Quick, Aidan! More questions! Stop me before I digress again!”

Aidan Moher: The Pathfinder Tales tie-in line features a wide range of authors, from newcomers like Josh Vogt and Wendy N. Wagner, to Hugo Award winners like Tim Pratt. I imagine it’s a lot like wrangling cats.However, despite the chaos, one of the things I like most about the Pathfinder Tales is that they all manage to have their own distinct voice, but also feel familiar and grounded in the same world. You have a hand in laying the groundwork for the world and its rules, which helps you with your own novels, but how do you work with your authors to ensure that their voice isn’t lost in the pre-established world of Golarion?

James L. Sutter: “I think the biggest thing is that I’m giving them *just* the world. When it comes to characters and plots, I make the authors generate those themselves, on the theory that they’re going to be more excited about ideas that are theirs from the start. While I wave them away from some ideas, and help them mesh their work with the world, we created the setting to host any kind of story, and they bring me mystery, horror, romance, black comedy, sword & sorcery…

“Of course, the authors are in some ways limited by the setting, in that the stories they tell need to work within the rules we’ve established — but remember, Earth is also a setting, with its own assumptions and defaults. If you were reading straight-up historical fiction, and suddenly gravity stopped working for a minute, or a tiger grew wings and flew across a lake, that’d knock a lot of readers out of their suspension of disbelief. Our game rules are the same way — an attempt to mimic the laws by which this fantasy world operates. And while working within that framework drives some authors nuts, others really enjoy it, as in addition to being able to outsource the work of worldbuilding (allowing the author to focus more on plot and character), constraints can breed creativity. Having well-defined magic systems make it hard for characters to simply magic their way out of every problem.”

Aidan Moher: It sounds a bit like they’re the historians of Golarion. They can see the sweeping vistas, some towns dotting the fields, they know the recorded history, but it’s up to them to delve into the stories, to search for the truth of what really happened and fill in the murky details.

James L. Sutter: “True! The novels aren’t histories, per se — they’re assumed to be happening ‘now’ in the setting — but the filling in the details aspect is spot-on. Through the novels, we get to experience the world firsthand, in ways game books alone don’t allow. It’s the difference between reading a travel guide and visiting yourself. Our authors sometimes invent whole new locations, but just as often they focus on the smaller brush strokes — the sights, the smells, the people you meet on the street — that make a setting much more personal and real.”

Aidan Moher: I’m really interested in your comment about how some of the constraints of writing within a pre-established world can actually breed creativity, rather than stifle it. For me personally as a writer, worldbuilding is, by far, the most difficult part of writing a secondary world fantasy. I want to get right into the nuts and bolts of the book: the action, the characters. Can you expand on this — perhaps from both your perspective as an author and an editor?

James L. Sutter: “You’re not alone — worldbuilding is in many ways a separate skill from storytelling, and a lot of authors find it difficult. I feel like, in SF&F particularly, books are a triangle of plot, character, and setting, and you can usually get away with having one weak side as long as the others are strong. (For example, I’d classify a lot of classics as falling into the “plot + setting” bin — you don’t read Tolkien for the characters’ complex inner lives.) But my point being: there are a lot of authors out there who are aces at plot and character, but come up with worlds that feel flat. For them, writing in a shared world is a huge advantage, because that third leg is being held up by a whole team of specialists.

“As an author, I find constraints really helpful in combating the Terror of the Blank Page. If you ask me to write a story — no specifications, just whatever I want — I’ll be paralyzed with options. All the possibilities will try to rush through the door at once and get stuck, cartoon-style, leaving me with nothing. But if you say “Hey, I need a story about lycanthropes in space,” I’ll have the manuscript for you on Monday. Like an oyster, I need that grain of sand to get me started before I can make a pearl*.”

“Shared-world work is full of that. With both of my Pathfinder novels, my outline started as a list of locations, monsters, and ideas from the setting that fascinate me. The plots and the characters were all the result of me asking myself “Alright, how can I tie together as many of these as possible together?” As an editor, I encourage my authors to do the same thing — if they come to me with a specific story type or character already in mind, that’s cool, but if not, I have them flip through our setting guide and bestiaries to see what sparks them. Inevitably, they come back with a dozen wildly different ideas they want to explore.

“(*Please note: “pearl” sounds arrogant when talking about my own work, but I mean it in the “congealed mollusc spit” sense.)”

Aidan Moher: I’ve been poring over the Inner Sea World Guide for weeks now, drawing inspiration from it as I brainstorm ideas for both short and novel-length fiction. I’ve found it fresh, invigorating, because Golarion is filled with so many ideas, never hampered by a preconceived notion of what a “fantasy” world should be. (There’s spaceships and mecha!)

It’s tough to create an entire world out of thin air, but one of the things that attracts me so much to Golarion, especially this early in its lifespan, is that while it’s expansive, enormous, there are still so many undiscovered corners. The map for a country like Varisia, for instance, is as dense and complex as those found in many of the most popular epic fantasy series, and it’s only one of dozens of countries in the Inner Sea Region (the main part of Golarion where the Pathfinder line is set). Other countries are huge, but only have a small scattering of towns and landmarks.

I know Josh Vogt, who debuted as a novelist with Forge of Ashes, was excited to explore the Five Kings Mountains, and had a hand in filling out the details for one of its major cities.

Do you find that some writers are more keen to face the “Terror of the Blank Page” than others — being more ambitious when it comes time to choose the setting for their story? Do you encourage new writers to adventure somewhere in Golarion that isn’t covered by one of the other authors?

James L. Sutter: “Absolutely — it all depends on what the author’s interested in. If I get an author who I know is great at worldbuilding, I’ll encourage him or her to set their story in a place we haven’t touched much yet, so that they can have a freer hand in developing that location and introducing details. If, on the other hand, an author isn’t as into that, and has given me an indication that they can handle really digging deep and learning the canon, then I’m happy to let them play in more established and recognizable locations. Perhaps contrary to what you might expect, it’s actually harder for me to find folks I trust to work in the most detailed places, because I have to do all the fact-checking on the novels myself, and if an author isn’t extremely meticulous, it means more work for both of us! If somebody’s going to write in, say, Korvosa or Westcrown — cities that readers are already really familiar with — they need to be prepared to approach the setting material with the same dedication as if they were writing historical fiction. Any sloppiness is going to instantly jump out at the audience.”

I’ve always felt that when you’re designing a setting, the questions are the point.

Aidan Moher: On the flip side, where’s the line between over developing Golarion to the point that it impedes on the creativity of gamemasters?

James L. Sutter: “I’ve always felt that when you’re designing a setting, the questions are the point. Details are cool, but it’s the half-explained things, the allusions and deliberate mysteries, that keep people awake at night wondering. Those are also the opportunities for game masters to tell their own stories. So our motto at Paizo has always been “Any time you answer a question, ask two more.” There will always be a fan for whom that’s unsatisfying — the people who feel like they need every answer in order for the world to feel real — and we’ve got parts of the world explicitly for those people. But as a reader, a writer, and a gamer, I want my imagination sparked so that I can make up my own answers, rather than just being handed all of them in a cohesive encyclopedia. A setting with no mystery is dead to me.

“The unexplained and undiscovered is also a key part of my world design process. I enjoy building things organically over time, so by dropping in random allusions the first time I write about something, I give myself easy starting points when I want to expand on that topic later. Kaer Maga — the anarchic, Mos Eisley-style city that’s one of my pet regions in Golarion — was one of the first and best examples of this. When I first introduced the city, I had extremely limited space, so I just threw in a bunch of proper nouns with hints at what they might mean. Bloatmages covered in leeches. Sweettalkers who sew their own mouths shut so as not to blaspheme. Wormfolk. The mysterious warriors of the Iridian Fold. People would constantly ask me about those things, and I would smile and wink despite having no idea what they were. Which of course got my imagination rolling, and eventually led to a full setting sourcebook, various adventures, my novel The Redemption Engine, and so on. Leaving yourself threads that aren’t tied up neatly is a gift to Future You — both a creative boost and job security.”

Aidan Moher: You just gave an answer, James. So, it’s time to pony up two more questions.

James L. Sutter: “Oh jeez! Hoisted by my own petard! Umm…

“As a reader, what do you most like to see in tie-in fiction? If you don’t currently read it, what would make you consider picking up a tie-in novel?”

Aidan Moher: To answer your second question first, I don’t read a lot of tie-in fiction, outside of the books that have broken into the pantheon of popular SFF — like R.A. Salvatore’s early Drizzt novels. Like many readers, I’ve been steered away from tie-in fiction by two (unfair) reputations: 1) they’re not good, and 2) they’re only for hardcore fans of the associated IP. However, lately I’ve been reading a lot of the Pathfinder Tales — spurred by news that some of my favourite genre folk like Max Gladstone and Sam Sykes are going to be contributing novels to the world — and I’ve quickly realized that those previous perceptions were (predictably) misguided.

This brings me back around to your first question: What do I enjoy about tie-in, and particularly the Pathfinder Tales? The mixture of familiarity and diversity.

Tie-in fiction offers a wonderful blend of something familiar and something new. As a reader, I enjoy being taken on adventures to new lands, but I also like visiting places that I’ve been before. So, I can turn to a place like Terry Brooks’ Four Lands (from the Shannara novels) — going there is like being welcomed home after a year abroad. At the same time, however, I quickly get sick of reading the same authors over and over again. I love the Four Lands, but grow irritated by Brooks’ repetition of storyline and plot devices. It’s not long before I get tired of the Four Lands, not because they’re boring, but because I’m constantly fighting the desire to move onto a different voice.

The Pathfinder Tales offer a terrific balance here. I’m becoming very familiar with Golarion — already have my favourite cities and cultures — but there’s always something new to explore because the world is so huge, so deep, and each author brings something new to the table. Looking for something introspective or contemplative? Wendy N. Wagner’s Skinwalkers is just the thing. Want balls-out action and humour? Try Tim Pratt’s City of the Fallen Sky. I love when I’m reading something by one author, and they mention a country or adventure that I’ve read about in a different book by a different author. I love that I can explore one world through the eyes of so many creative people.

In fact, this approach to world building, creating a place of vast potential, where no country is the same, and each exotic corner offers something for the reader to discover — a new magic, new cultures, new adventures — has had a huge impact on my own approach to world building. I want a playground with limitless boundaries, where anything can happen. This allows a writer to explore all sorts of stories without boundaries.Now who’s being long-winded?

James L. Sutter: “I’m going to steal that note about multiple authors keeping a setting fresh. That’s spot-on.”

Aidan Moher: Say I’m a new author, freshly born into the Paizo family and about to begin work on my first Pathfinder novel. Take me through the process.

James L. Sutter: “To backtrack a little, first an author has to get in the door. Part of my mission for the line is to only get the best possible authors for these books, which means that competition gets steeper every year… you’re competing for schedule slots with those same authors you mentioned earlier.”

Before I started editing novels, I was terribly intimidated — how could I possibly write a story that long?

Aidan Moher: I’ll admit that this first drew me to giving the Pathfinder Tales a look — with authors like Tim Pratt (who’s won a Hugo Award!), Liane Merciel, and Howard Andrew Jones involved, I knew Paizo took their universe seriously, and the addition of upcoming novels from Max Gladstone and Sam Sykes pushed me over the edge. There’s nothing like seeing a bunch of great authors excited about a new IP, and I haven’t looked back since.

James L. Sutter: “There’s no open submissions — please don’t write a Pathfinder novel on spec! — but authors who’ve had some pro-level sales are welcome to email me with a writing sample, meaning a couple of short stories or chapters from a novel. I don’t require that it be sword & sorcery specifically — I’m a firm believer that a great writer can hop between genres. But if I feel like the author’s skill and style is a good fit, then they’re “in” — but the work is just beginning.

“The first thing we do is pitching. I encourage authors to send me a shotgun blast of at least half a dozen ideas of just a few sentences each — “Character X does thing Y in nation Z.” That allows me to quickly nix any that I don’t like, or that are too close to things we’ve already done or have on the schedule. Sometimes pitching can take several rounds before something intrigues me enough to give the go-ahead. I’m also happy to have authors pitch me parts of an idea — say a character, or a type of story — and to work with them to craft the right pitch together. So if an author comes to me with a cool character concept, I can help match it to the right region or organization within the world.

“Once we’ve got the right pitch, I have them write up a short outline — a few paragraphs. That’s often the point at which I take it around to some of the other senior managers and continuity folks at Paizo and make sure everybody’s on board. If they are, I have them expand it to a full chapter-by-chapter outline, usually about 5,000 words, which shows every twist and turn of the plot, any magic or monsters that are key to the story, etc. Only when *that’s* approved is a novel officially greenlit.

“This might seem really elaborate, with so many rounds of feedback, but in a project like this, I need to be able to vett as much of the novel in advance as possible. Tie-in has a lot of potential pitfalls, and if an author’s misunderstanding of how a given spell works breaks the plot, I’d rather have them revise a few thousand words of outline than 90,000 words of manuscript. So far, the policy’s worked pretty well.

“Once an outline’s greenlit, the author’s free to write. In general, I let the authors set their own deadlines — some people can turn a novel around in a few months, others need a year or more, and I’d rather give a book a later release date than have it feel rushed. How much an author and I interact during the writing is up to them — while some know the rules and world inside and out, most email me pretty regularly with questions, and I answer them and make sure they’re provided with the most pertinent sourcebooks for the topics they’re writing about.

“When the novel comes in, I go through it with an eye toward both rules/continuity and story development, then send the author revision notes. When the revised manuscript comes back, I edit it (along with Paizo Senior Editor Chris Carey), we get it all laid out and prettied up, then ship it off to Tor for production.”

Aidan Moher: From a more personal perspective, what were you able to take from the experience of writing your first novel, Death’s Heretic, into writing your second, The Redemption Engine?

James L. Sutter: “Confidence and fear. The former came from the fact that I had empirical proof that I could, in fact, write a novel. That’s worth a lot. At the same time, I had a terrible fear of what I call Sophomore Album Syndrome — Death’s Heretic had gotten some nice accolades (hooray!), but how could I have any assurance that I could repeat that magic trick? As my wife is fond of reminding me, when I finished The Redemption Engine, I said, “Well, I don’t know if it’s great, but it’s at least good — and it’s done.” (As it turns out, the audience has near-universally declared it better than my first book, so I’m pretty sure there’s a lesson there.)

“But to dig a little deeper into that confidence part — I think that seeing a book all the way through its life cycle erases a lot of the mystery from the process, and that’s a huge boon. Before I started editing novels, I was terribly intimidated — how could I possibly write a story that long? But then I spent a few years looking behind the curtain — helping authors craft pitches and outline stories and patch up broken manuscripts — and realized that books don’t spring fully formed from your head. You assemble the bits and pieces, and sometimes a part’s missing or wrong and needs to be replaced, and suddenly this doesn’t seem like the Great Mystery of Art, but rather a craft you practice. That gave me the confidence to start Death’s Heretic, and knowing that I could finish Death Heretic gave me the confidence to plug away at The Redemption Engine, a thousand words at a time, for the two years it took to complete.

“One note about that, though. I wrote a bit on Chuck Wendig’s blog about things I learned writing The Redemption Engine, but I want to reiterate the most important one, which is that at some point I’m going to die. And when I die, it won’t matter if I’ve published one book or a hundred, because I’ll be dead. That realization, while morbid, really helped free me from the frantic race to write as much as possible. Writing professionally is an awesome job, but it’s still a job, and that old adage about how nobody dies wishing they’d spent more time at the office still applies. So I encourage everyone to look askance at the advice that says writers must sacrifice for their art. As soon as I gave up that constant nagging voice saying “I should be writing” and allowed myself to wholeheartedly embrace other activities and adventures, I started enjoying life a lot more — and found that I still got almost as much writing done.”

Aidan Moher: How does being the series editor affect your approach to writing your novels? Do you get carte blanche approval to do whatever you want? ;)

James L. Sutter: “If only! While it’s true that being one of the setting’s creators means I’m generally trusted to play with the most beloved toys, I’m still absolutely beholden to my colleagues and the audience, and I take that responsibility seriously. For instance, in The Redemption Engine, the heroes spend a lot of time in Heaven and Hell, both places that Paizo Editor-in-Chief Wes Schneider is deeply invested in, so he and I spent a lot of time talking about them. And Creative Director James Jacobs and I have a long-standing and good-natured argument about the alignment system, primarily because I love to subvert it and introduce moral ambiguity. So when I decided to put angels and devils in my relativist blender, I knew that I’d need to craft things just right to make something that felt good to both of us. And of course, I don’t edit or develop my own novels — my colleagues have been more than happy to step in and hold my feet to the fire!

“But yeah, all of that aside — it’s really fun to get to cherry-pick creatures and locations that I’ve created, as well as those of my colleagues. My novels tend to start out as questions about the setting — ‘What does it mean to be an atheist in a world where gods are empirically real?’ ‘What are the moral implications of magically turning an evil person good?’ — and then quickly become an effort to shove in as many toys as possible. Did that central question of Death’s Heretic *require* a planes-hopping adventure full of snarky psychopomps and singing chaos snakes and robot cops and gravity-reversing jellyfish? Of course not. But those things are awesome, and I figure that the best way to ensure an audience has fun reading a book is for me to have fun writing it.”

Aidan Moher: It strikes me that your many roles at Paizo — editor, author, world designer, gamer — revolve around collective, collaborative storytelling. What are your thoughts on collaborative storytelling, and its effect on linear (novels) and non-linear (RPG campaigns) narratives?

James L. Sutter: “Collaborative storytelling — collaborative anything, really — is a blessing and a curse. While it’s easy to get exhausted or frustrated by having to advocate for your ideas or accommodate others’, I find that as long as you’ve got the right crew of collaborators, the final result is always better than the individuals could create on their own. I encounter that all the time, whether it’s working with my colleagues to continue building the Pathfinder setting, advising authors on ways to patch holes in their novel outlines, or simply getting feedback from friends on my own stories.

“RPGs are collaborative storytelling in its purest form. Everybody gets to contribute, and the story can go anywhere. That’s the fun — that sense of opportunity, the chance for everyone (including the Game Master) to be surprised. At the same time, there’s a reason why direct adaptations or journals of RPG campaigns rarely make good novels: they’re meandering, full of dead-ends and side treks that were fun in the moment but of limited interest to those not playing — in other words, they’re non-linear, just like real-life. As humans, we live non-linearly, so we tend to want our stories to be linear — it’s that idea that there’s a point to things, or at least a climax, that keeps us engaged.

“Man, good thing we’re reaching the end of the interview — this is getting pretty meta. Thanks to everyone who made it this far in James and Aidan’s Story Philosophy 101 — office hours are 11:00 to 7:00 on Twitter, and your term papers will account for 100% of your final grade.”

Aidan Moher: It was a pleasure to have you, James. I won’t mention to your readers that this interview is almost long enough to count as a novelette.

James L. Sutter: “That’s okay — blog posts are paid by the word, right?

*someone passes in a note from off-camera*

“Wait, really? How come there are so many bloggers, then? The internet is so confusing!”

Aidan Moher: Now, excuse me while I wander off to badger my friends into starting up a new Pathfinder campaign. There’s a gravity-reversing jellyfish who needs dealt with.

James L. Sutter: “Thanks again, Aidan! This was a blast!”

Oh, a most excellent, detailed and in depth interview, Aidan. Much meatier than I expected, and in a very good way.

And I love that Golarion map

Thanks, Paul! This was a long time in the making, and we had a lot of fun digging into Pathfinder, and all the associated bits. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

[…] Aidan Moher on A Dribble of Ink […]

[…] the only one surprised at this level of quality from a series of tie-in novels, as you can see in Aidan Moher’s interview with James L. Sutter, one of the Paizo developers and in charge of the line of […]