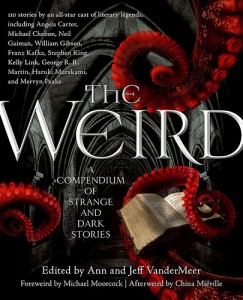

This week saw the publication in the U.S. of a massive (Amazon shipping weight for the hardcover: 3.1 pounds!) new anthology of fantastic literature: Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. Initially published in the U.K. by Corvus last fall, this book contains 110 stories of fabulous, bizarre, sometimes esoteric weirdness. I read the whole thing at the end of last year, and it has produced a lot of fodder for contemplation. I found it difficult to write a brief, crisp review of it (although a review is in progress), but what really made this book significant to me is that I have been able to turn the stories over and over in my mind and find insights into reading, writing, story, genre, and some tenebrous insights into how I look at life and reality. Even better, some of the stories require you to struggle, to navigate your way through discomfort and perplexity, to really experience their value. I’ve written about it several times, and it has inspired a chapter in the book I’m currently working on. What’s great about The Weird is that you can find all kinds of odd, perplexing, sometimes horrible things in it, and once you take them in they start to worm themselves into your thoughts and ideas.

This week saw the publication in the U.S. of a massive (Amazon shipping weight for the hardcover: 3.1 pounds!) new anthology of fantastic literature: Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. Initially published in the U.K. by Corvus last fall, this book contains 110 stories of fabulous, bizarre, sometimes esoteric weirdness. I read the whole thing at the end of last year, and it has produced a lot of fodder for contemplation. I found it difficult to write a brief, crisp review of it (although a review is in progress), but what really made this book significant to me is that I have been able to turn the stories over and over in my mind and find insights into reading, writing, story, genre, and some tenebrous insights into how I look at life and reality. Even better, some of the stories require you to struggle, to navigate your way through discomfort and perplexity, to really experience their value. I’ve written about it several times, and it has inspired a chapter in the book I’m currently working on. What’s great about The Weird is that you can find all kinds of odd, perplexing, sometimes horrible things in it, and once you take them in they start to worm themselves into your thoughts and ideas.

Well, they do for me at least.

And this is what I want to discuss in this blog post: the idea not just of weird fiction, but of how genre expectations — as reading frameworks — condition our engagement with fantastic literature. We all have our preferred categorizations for the stories we read: some people like SF, others speculative fiction or fantastic fiction. Some readers want to organize stories more precisely, right down to very specific sub-genres like paranormal romance or steampunk. Some people like micro-designations, while others like a big playing field. Myself, I was a rabid, obsessive parser of subgenres as a younger reader, but I found after some years that I was reading the same sort of stuff constantly, and I was getting, well, bored. I came to realize that my problem was with how I looked at genre, how I used genre and how my expectations and assumptions influenced my reading of a story. I have evolved into a big-tent sort of reader of fantastic fiction, to the point where I prefer to use the term fantastika, precisely because it opens doors into stories rather than closing them. It also incites discussions about genre and how we look at the stories we enjoy reading, and I like that. Read More »