“The thing is,” I pointed out, “It’s all work. This is work.”

“The thing is,” I pointed out reasonably, “I’m working even when my fingers aren’t physically pressing the keys.” I pointed helpfully at my head, trying to indicate the furious labor going on inside. “Writing is not a linear process. It’s all work. This is work.”

My argument might have been more compelling if I hadn’t been standing in my boxer shorts at 2 o’clock on a Tuesday afternoon drinking an IPA and watching the local porcupine trying to snag that last apple without falling out of the tree.

“You may be working,” Jo replied, “but I want to punch you really hard in the neck.”

It seemed like an uncharitable thing to say to a man who was hard at work writing his second novel. It seemed doubly uncharitable given that Jo is my wife, and that our division of labor – the very division that led me to be standing on the porch in my boxers in the first place – was something we had hammered out together, something we had both happily embraced.

I pointed this out. The things she said next were even less charitable. Read More »

“Jane Navio was a chrome-assed bitch … but she was right.” Up Against It, M. J. Locke

I wish there were more Jane Navios in fantasy. Oh, you see them in science fiction and horror, but not in fantasy. There is an unwritten code that women in fantasy novels must not be older than thirty, or they’re all the grandmotherly types over sixty, but rarely are there any in the forty to fifty range. There are a few exceptions to this rule, but since the 1990s, female characters over forty seem to have faded into the background scenery, and very few are protagonists.

Part of this is our current culture. I see it every time I go online. So-and-so actress is aging well, but only because she appears as if she is ten or twenty years younger. Helen Mirren and Dame Judi Dench are the exceptions to this rule. Both of these ladies have played chrome-assed bitches in their films. They don’t waffle or give long, righteous speeches about women and what they need. They wade right into a situation and get the job done.

The genre community talks about writing worlds that are a clearer reflection of the world in which we live, yet no one talks about the need for older protagonists. People don’t cease to exist after thirty, nor do they turn into fountains of knowledge and wisdom. Old bearded men, who guide young men, or ancient wise women, who are kind and giving, simply don’t exist in abundance in the real world. It’s easy become lost in the wonder of youth, but wonder does not automatically stop after a certain age. Even at fifty, I am still discovering new aspects of self and the world around me.

Like everyone else, older people like to see themselves reflected in the fiction they read. When I posed the question on Twitter one day, people were quick to mention George R.R. Martin’s Catelyn and Cersei as good examples of mature women in current literature, and I can’t disagree. Of the two, I’d say that Cersei falls closer to chrome than Catelyn. They are the biggest reasons I’ve stuck with the series as long as I have. Read More »

Author’s Note:

This piece is meant to be a broad-ranging retrospective on the work of Gene Wolfe, one of the most significant authors of speculative fiction. As I imply in the essay below I think it is quite impossible to “spoil” a Gene Wolfe novel (each work is just too protean), but I do discuss both his plots and possible interpretations of several puzzles his books present. So if you haven’t read the books in question, you’ve been warned.

A good essay, like any good story, needs solid bones.

A good essay, like any good story, needs solid bones. It needs a foundation, a structure, a framework on which the subject can hang. When I sit down to write about a genre, or a story, or an author’s work I always start with that core: I try to find some central tenet, a grain of sand small and indivisible, some immutable truth inherent to the work around which my analysis can accrete. But trying to sift the work of Gene Wolfe – one of my favorite authors – I find that each grain becomes as mutable, as multifaceted, as slippery as his work itself. And maybe it is that slipperiness, that coy teasing play, that is itself the heart of Wolfe’s writing. Perhaps that is as good a place to start as any.

Gene Wolfe – as he has stated time and again – sets out to write books which can deliver a different kind of enjoyment each time they are read or re-read. He engineers his work from the very start to operate on multiple levels, to manipulate the reader using different levers.

Read More »

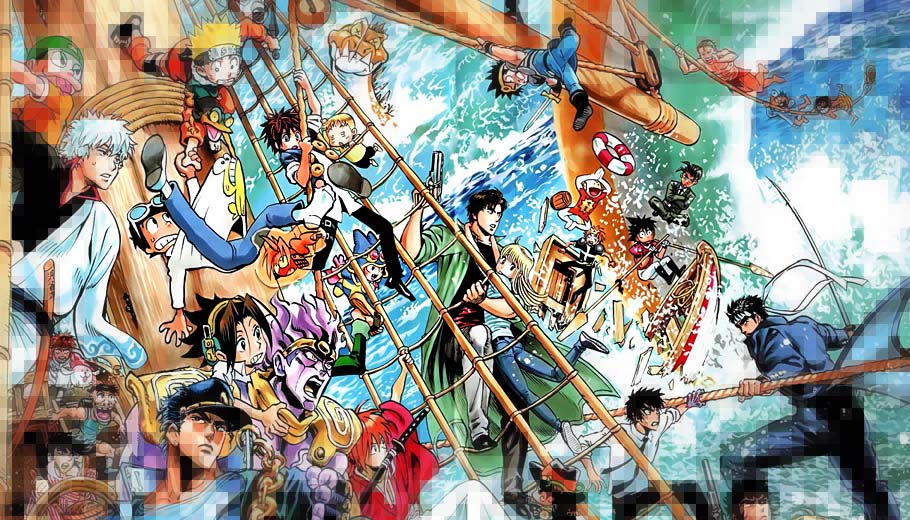

I’ve read an awful lot of fantasy, and watched an awful lot of anime, and both canvases are incredibly broad and notoriously hard to characterize.

When first discussing this essay, comparing and contrasting the traditional hero narrative in fantasy fiction and anime, with my friend Casey Blair, I found myself in a bit of difficulty. I’ve read an awful lot of fantasy, and watched an awful lot of anime, and both canvases are incredibly broad and notoriously hard to characterize.

Fantasy, after all, includes classics like Lord of the Rings, heroic secondary-world epics like The Wheel of Time, wainscot fantasy like Harry Potter, and the magical realism of The City & The City, covering sub-genres like urban fantasy and steampunk in between. It’s very hard to write a coherent comparison that covers both C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia and Max Gladstone’s Three Parts Dead, for all that we shelve them in the same genre.

Similarly, anime is unbelievably diverse, more so than all but the most hardcore of fans realize. (Because the US translation companies skim the cream of the crop, picking the hit shows and often passing over the stuff with less broad appeal.) From staples like Dragonball, Sailor Moon, or Naruto, anime goes all the way to Revolutionary Girl Utena (which is so symbolic as to be almost abstract) and Non Non Biyori (which is about a bunch of girls in a rural village chatting about nothing in particular). It includes every genre of speculative fiction we have in the US, and some we don’t. Read More »