I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark.

I was asked for this post to write about hope in fantasy. And that means I need to talk about grimdark. (Definition from TV Tropes here, for those who need it.) And I need to say, before I start, that I am a practitioner of grimdark; the Doctrine of Labyrinths quartet (Melusine (2005), The Virtu (2006), The Mirador (2007), Corambis (2009)) can be nothing but. So I’m not speaking as someone who abhors grimdark, but as someone who loves it.

One of the things behind grimdark, I think–and it’s not just grimdark, either, but most of Anglophone literature since somewhere around World War I–is a conviction that being pessimistic, tragic, depressing, dark means that a text is more “realistic,” more “serious,” and therefore inherently “better” than it would be if it allowed optimism and hope. I’ll get into the issue of “realism” later, but I want to point out here that tragedy is not inherently “better” as a literary form than comedy and writing a tragedy does not demonstrate greater skill/talent/genius than writing a comedy. (Kind of the reverse, in fact. Comedy is hard.) Read More »

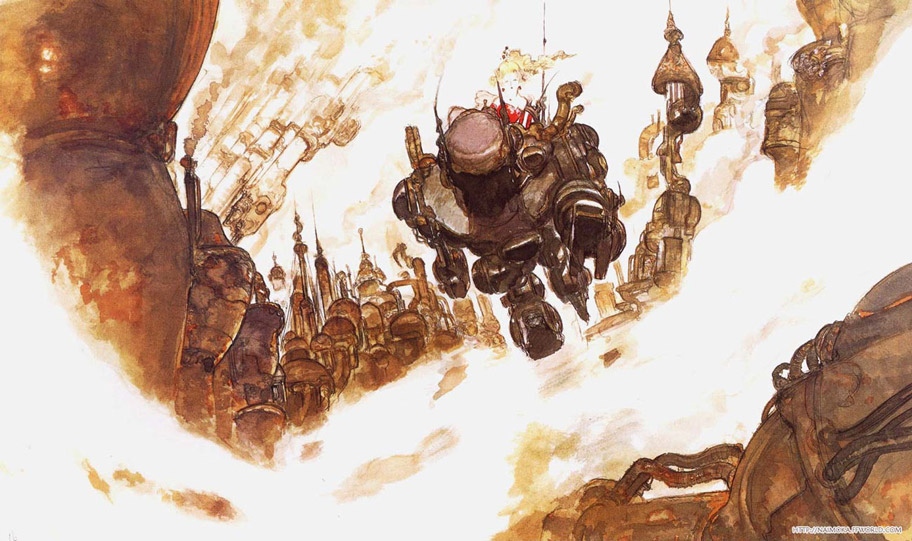

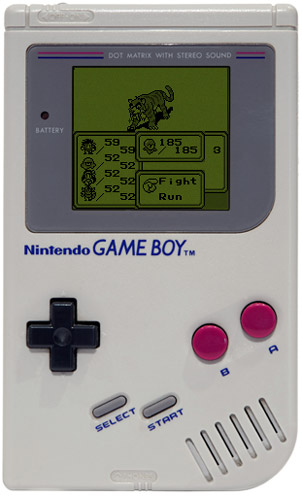

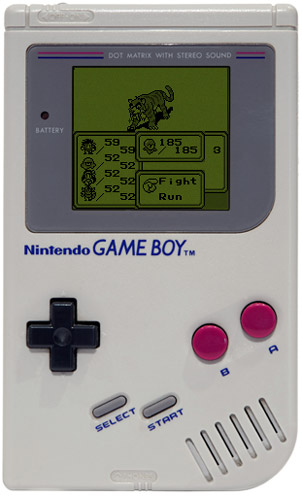

I still remember the first time that I saw a Japanese Roleplaying Game (JRPG). Like many people of my generation, it was a Final Fantasy game, though not one so obvious as Final Fantasy, Final Fantasy VI (or Final Fantasy 3, if you’re familiar with the North American naming scheme), or Final Fantasy VII. No, it was Final Fantasy Legend II in all of its monochromatic glory on the Nintendo Game Boy.

I was at a friend’s house, and his cousin was also visiting. I’d never met the cousin, but he had a Game Boy (like me), so I liked him almost instantly. But, where I was eradicating (or, more accurately, being eradicated by) the Footclan in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or dodging winged-Moai statues in Super Mario Land, he had this slow, boardgame-like game, with numbers, equipment, a map, and so many other elements that I was unfamiliar with. In particular, I remember a fight with a tiger. The one pictured here, in fact. As I think back on it, I can only assume that it’s a low level enemy, fought in one of the early game environments. At the time, however, it was something different. Something frightening.

If you do your homework, however, you’ll quickly discover that my first experience with Final Fantasy was, in fact, not with Final Fantasy at all, but with Akitoshi Kawazu’s infamous SaGa series. See, when Square the developer of the Final Fantasy series, wanted to bring over Kawazu’s zany Makai Toushi SaGa, the first in the SaGa series, to North American shores, they decided that it made more sense to release the title under a respected and successful brand, Final Fantasy, rather than attempting to sell something new. It was the right decision. Final Fantasy Legend II became Square’s first million-selling product. Read More »

If it wasn’t for unconventional publishing, that would have been the end of the road for Hollow World.

Publishing today is a complicated business full of many options and proponents on different sides vocalizing their path is “the right one” with full-throated conviction. For the record, I see the advantages (and disadvantages) of each. I also don’t think there is a “universal right choice,” just a choice that is going to best fit on an author by author basis.

Currently I’m a ‘hybrid author‘ because I have works available both through self-publishing and traditional routes. What’s more, my traditional routes include both big-five and small presses and there is a world of difference between them.

I think Hollow World, my latest novel, was probably produced in one of the most unconventional ways possible. First it was submitted to my publisher, Orbit. My editor loved the book, but the marketing department didn’t. They need to focus on what sells (and I don’t begrudge this mindset) and currently they think that means military science-fiction and space operas. A classic-style, social science fiction novel such as those written by Asimov or Wells just didn’t fit the bill.

If it wasn’t for unconventional publishing, that would have been the end of the road for Hollow World, and I know far too many authors who have shelved books because they couldn’t get them picked up (or were offered too little). But from past experience, I knew a closed door just means I should look around for an open window. Read More »

A young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

A minor noblewoman has a tragic love affair with an emperor. She dies, leaving behind her child — a young man of surpassing beauty who rises to a political and romantic career of power and renown mixed with disappointment, betrayal, and demonic possession. Also, he glows.

Welcome to the Tale of Genji, the Japanese story of romance, ghosts, poetry, and politics that has a good claim of being the world’s first novel. To clarify: Genji is a work of prose, not epic poetry, and written in the vernacular rather than the local courtly language (which, in early 11th century Heian Japan, would have been Chinese). It’s also, as far as we can tell, original, without folkloric or legendary precursor. The author, Lady Murusaki Shikibu, wove her hero and his, um, exploits out of whole cloth. And, while many other works deal with mythological high society—gods and demons and so forth—Murusaki seems to have cared a great deal about representing (idealistically but still) her social reality. Genji Monogatari is a work of beauty and passion and (to modern sensibilities) occasional utter weirdness, in which twenty chapters of plot turn on the accidental glimpse of one character by another through a paper screen, astrological prohibitions on travel are used to justify spending the night at a prospective lover’s house, titles take the place of names, violence is anathema, and a twenty-mile exile is worse than death. Read More »

I would see queer romance in a different, more nuanced light, complete with a historical perspective that both undercut Card’s work and crystallized the notion of real-world men who loved each other with their bodies as well as their minds.

Hello A Dribble of Ink! I am David Edison, author of The Waking Engine and editor of GayGamer.net, and I am dribbling my ink all over you. Aidan has asked me to talk about my experiences with inclusivity in the gaming world, which is a great chance to look at the differences and similarities with the equivalent challenge in the world of speculative fiction. I’ll apologize in advance for being unscholarly and scatterbrained: these are, of course, sprawling and complex dynamics, and a genuine analysis is beyond both the scope of a blog post and the capabilities of yours truly.

Let’s start with the idea of finding yourself reflected in the creative works you consume. From my personal experience: I encountered a representation of my own queerness in speculative fiction well before I encountered it anywhere else in our culture, especially games. Orson Scott Card’s Songmaster hit me like a ton of bricks at nine, maybe ten years of age. (There is irony to be found there, of course, which is its own post, methinks.) The pedophilia went right over my young head (paging Alanis Morissette and her 10,000 not-actually-ironic spoons, and yet another blog post), but what mattered to me then, as now, was the love. Only a few years later, when I read Mary Renault’s stunning historical novels like Fire from Heaven, The Mask of Apollo, and The Persian Boy, I would see queer romance in a different, more nuanced light, complete with a historical perspective that both undercut Card’s work and crystallized the notion of real-world men who loved each other with their bodies as well as their minds.

For a young queer man, especially a reader, discovering multiple sources of my own nature (which I had realized at a much younger age than 9 years old, though I did not have the words for it) was a lifeline: suddenly I was a part of the world. Moreover, I could decide between different representations of myself and begin building an identity in concert with reality, rather than wondering if perhaps, to my horror, I might be the only one. Read More »